Will Europe's Philae Comet Lander Make Another Comeback?

The team operating Europe's resilient Philae comet lander hopes the probe can pull off one more dramatic comeback.

The Philae lander has been incommunicado on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for three weeks as the icy object has been speeding toward its closest approach to the sun, which will occur Aug. 13. The lander team would love to get Philae up and running again soon so that they can get an up-close look at how this "perihelion passage" affects 67P.

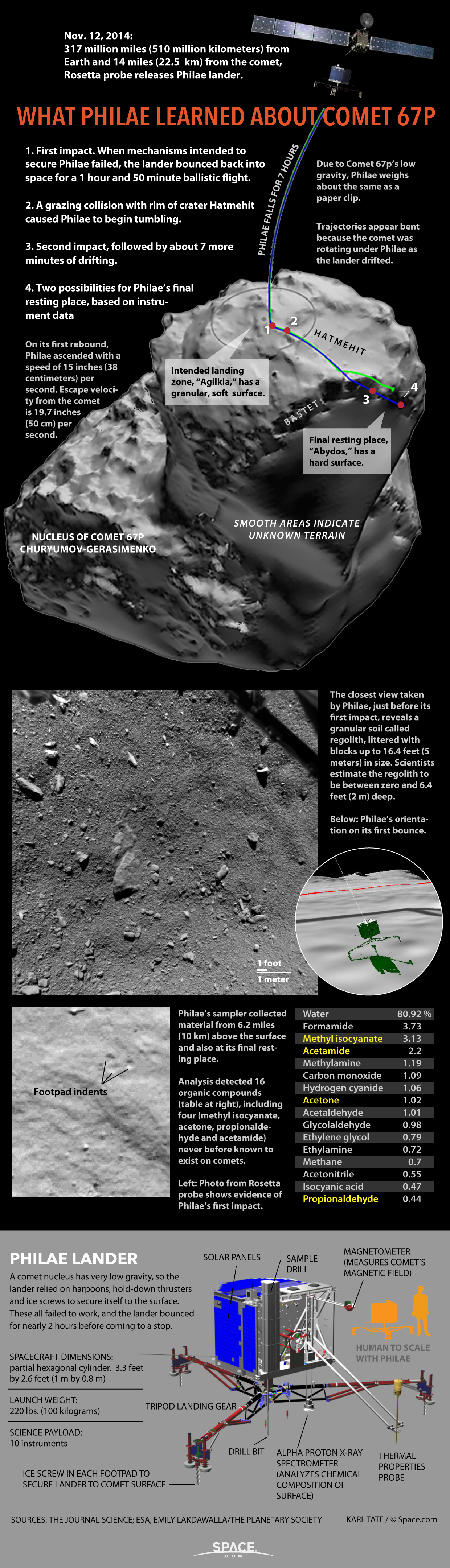

The washing-machine-size probe has certainly bounced back before. It survived a harrowing double-bounce touchdown on Nov. 12, and then gathered a wealth of data on the surface of Comet 67P with its 10 science instruments for more than two days. [Philae's Historic Comet Landing: Complete Coverage]

This work ended when Philae's primary battery died and the probe went into hibernation — a consequence of coming to rest in an unexpectedly shaded location. (Philae's secondary battery is rechargeable, and the original landing plan had the probe operating in a spot where sunlight could keep it powered up.)

A recharge did end up happening, though it took much longer than planned: Philae phoned home on June 13, apparently revivified by the increasing levels of solar radiation it experienced as Comet 67P got closer and closer to the sun.

But communications between Philae and the ground have been spotty, despite the best efforts of the lander team. Operators did manage to command Philae to take some new data with its Comet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Radiowave Transmission (CONSERT) instrument early this month, but they haven't been able to contact the lander since July 9.

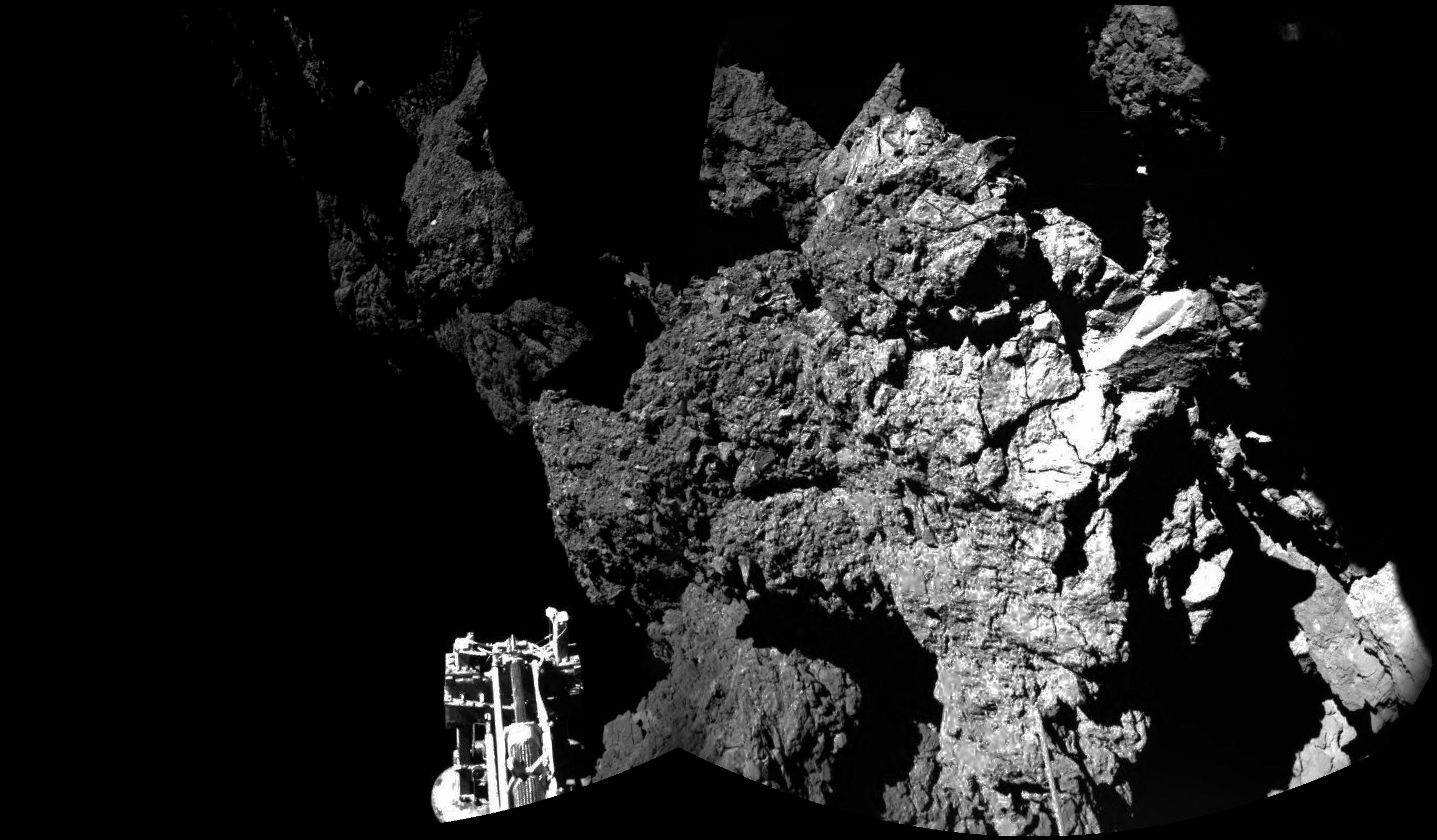

It's unclear what, exactly, is going on. One possibility is that Philae's position has shifted since July 9, changing the orientation of its antenna and therefore making it tougher for the lander to communicate with its Rosetta mothership (which is orbiting 67P and relays data from Philae back to Earth).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When you see what's happening on the surface of that comet — jets going off, and God knows what else — it wouldn't take a lot of that going off close to the lander to move it around a bit," said Ian Wright of The Open University in the United Kingdom, principal investigator of Philae's Ptolemy instrument, which measures stable isotope ratios of molecules on 67P.

One of Philae's two transmitters also may not be working properly, European Space Agency officials said. The 220-lb. (100 kilograms) spacecraft is programmed to switch back and forth between these two transmitters; the team is now trying to get Philae to use the functional one exclusively.

"Philae is obviously still functional, because it sends us data, even if it does so at irregular intervals and at surprising times," Philae project manager Stephan Ulamec, of the German Aerospace Center (DLR), said in a statement last week. "Several times, we were afraid that the lander would remain off — but it has repeatedly taught us otherwise."

Mission team members will continue trying to contact Philae, but they will also be busy making sure the Rosetta orbiter is doing all it can to document the changes on 67P wrought by the upcoming closest solar approach.

On Aug. 13, the comet will come within 1.24 astronomical units (AU) of the sun. When Philae landed in November, 67P was about 3 AU away from our star. (1 AU is the distance from Earth to the sun— about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

"The design of the Rosetta trajectory is adapted to meet its science objectives, and we are in particular heading toward southern latitudes since July 24, in order to explore regions of the comet which are just starting to receive sunlight, after years spent in the dark," Nicolas Altobelli, acting Rosetta project scientist, told Space.com via email.

"In addition to addressing the primary science goals of Rosetta, we will come back regularly to latitudes where communication with the lander could be possible," he added.

Wright has a hunch that Philae won't stay silent forever. After all, if a jet did indeed knock Philae out of alignment with Rosetta, another eruption could just as easily blast it back into the proper orientation.

"I suspect that the communication will come back at some point, as a complete surprise, and it'll be, 'Wow, we didn't expect it to be in that line of sight,'" Wright told Space.com. "That's my personal feeling about it, but it's in no way a formal or official position."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.