See Double Crescents of Venus and the Moon with Binoculars

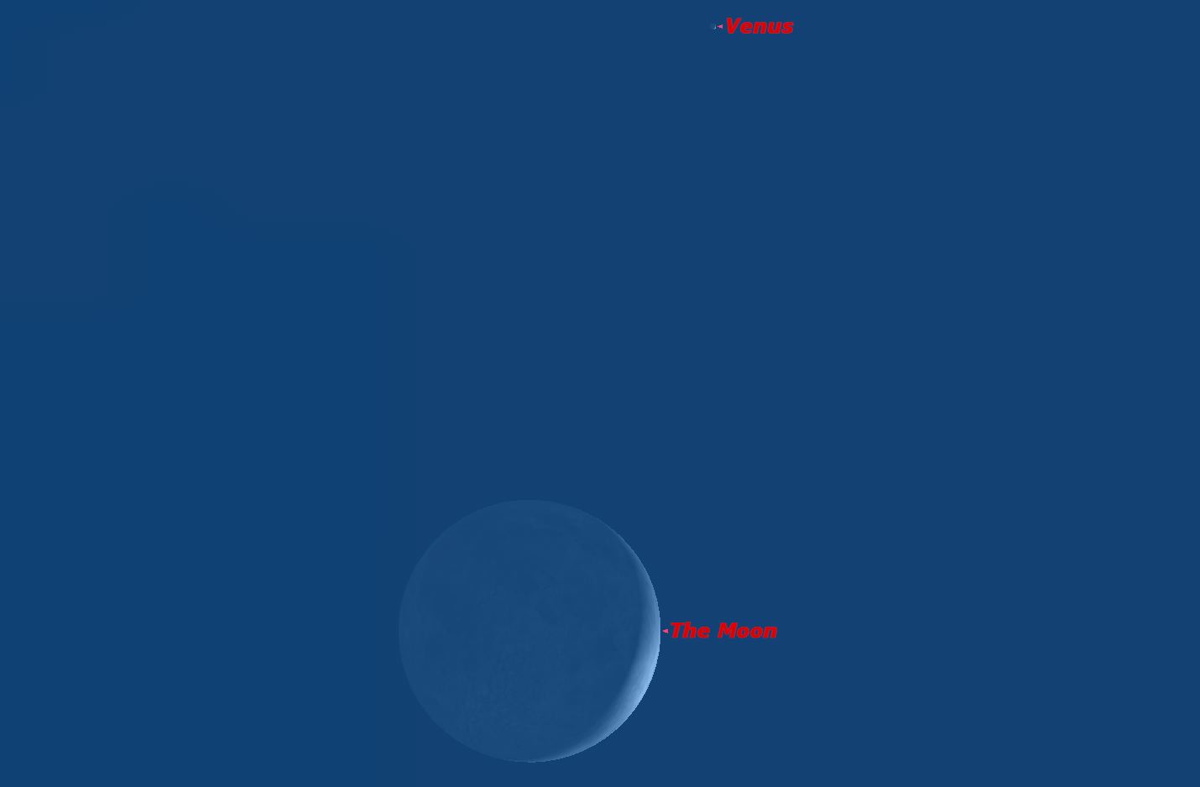

On the evening of Saturday (July 18) the crescent moon, as it moves eastward across the sky, will appear to pass directly below the crescent planet Venus, which itself is moving westward across the sky.

Both objects are being lit by the sun in such a way that both appear in our sky as crescents. The moon is just three days past new moon, so only 9 percent of its disk is lit by the sun. The remaining 91 percent is lit by sunlight reflecting off the surface of the Earth, what is called "earthshine"or "earthlight." Sometimes this view is also called "the old moon in the new moon's arms."

To the naked eye, Venus appears like a brilliant pinpoint of light. Turn your binoculars on it, and that slight additional magnification will allow you to see that Venus is also a narrow crescent. [Best Binoculars for Astronomy (Editors' Choice)]

Because Venus is farther away than the moon, it is lit by the sun at a slightly different angle, so is nineteen percent illuminated, a slightly fatter crescent than the moon.

Some observers have suspected a faint glow coming from the part of Venus not in direct sunlight, a phenomenon called "the ashen light."No one knows exactly what causes this glow, but it has been reported by many experienced astronomers. Spectroscopic observations have shown pulses in the light, so it might be due to lightning in the hot acidic atmosphere of Venus.

As mentioned above, even small binoculars provide enough magnification to turn the naked-eye pinpoint of Venus into a visible crescent. This is one of many objects in the sky which are revealed or enhanced in binoculars, which is why they are considered an essential tool for all serious skywatchers.

Binoculars for astronomy should have a front aperture of at least 50 millimeters (2 inches). This is seven times the diameter of the fully dark-adapted eye. Such a small binocular has seven times the resolution and 50 times the light-gathering power of the naked eye.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A pair of 50-millimeter binoculars come in two magnifications, 7 power (7x50) and 10 power (10x50). Both are very useful for astronomy, but I prefer the 10x50 because of its slightly higher magnification and better contrast in a bright sky. I find more powerful binoculars too heavy to hold steadily for any length of time, and mounting them on a tripod defeats the ease of use.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.