After Pluto Flyby, NASA Plays the Waiting Game

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

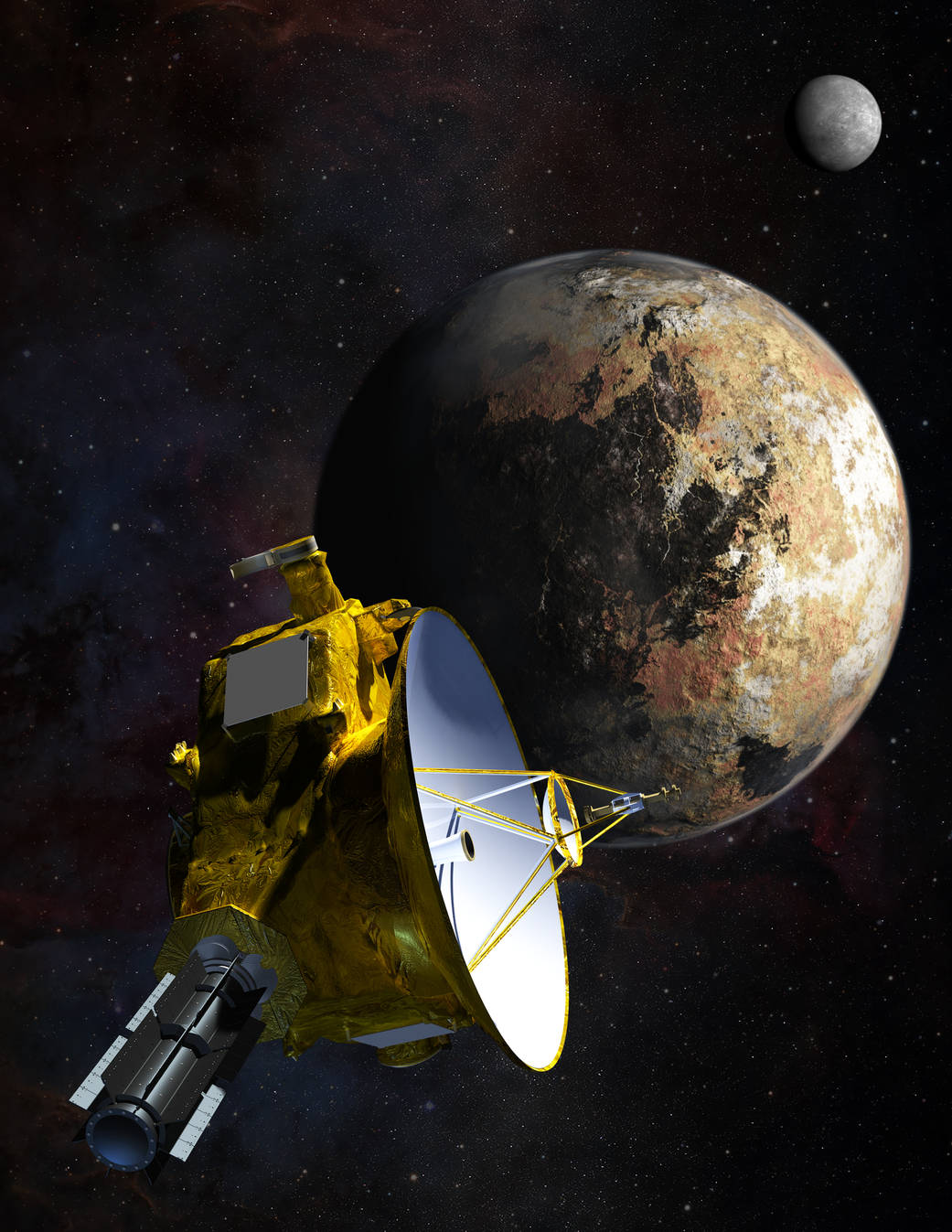

LAUREL, Md. -- Although NASA's New Horizons spacecraft made its closest approach to Pluto this morning (July 14), mission operators won't hear from the probe until tonight, and images of the pass-by won't be released until tomorrow (July 15).

New Horizons zoomed within 7,800 miles (12,500 kilometers) of Pluto at 7:49 a.m. EDT (1149 GMT) today, performing the first-ever flyby of the dwarf planet. The probe's handlers don't expect to hear from New Horizons until 9 p.m. EDT (0100 GMT Wednesday) or so tonight.

But the reason for the long silence isn't ominous — the blackout has been planned since the early days of the mission. [New Horizons' Epic Pluto Flyby: Complete Coverage]

"This is a mission of delayed gratification," New Horizons scientist Randy Gladstone, of the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, said during a news conference Sunday (July 12).

Long-distance call

A major cause of the delay involves the enormous distance the message back to Earth must cross. New Horizons is now nearly 3 billion miles (4.8 billion kilometers) from Earth, so a signal from the spacecraft takes about 4.5 hours to reach the people eagerly awaiting its call.

To catch the signal, NASA is relying on three separate arrays of 230-foot-wide (70 meters) radio dishes that make up its Deep Space Network. Located in southern California, Spain and Australia, the three antennas are located nearly 120 degrees apart on Earth's globe, allowing for constant communication with spacecraft in the solar system. Before the first dish sinks beneath the horizon with the planet's rotation, the next site has already made contact.

For New Horizons, the Spain array should make first contact at 8:53 p.m. EDT tonight (0053 GMT Wednesday), picking up the signal from the outer reaches of the solar system. The spacecraft will transmit to Earth for 16 minutes, sending only telemetric data that tells the team about its status.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"In this telemetry we will learn, in a general sense, if the spacecraft is healthy," said New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

The team will be able to look for any signs that would indicate if the software took unexpected action. They will also see the recorder status, checking to see if the data record is filling up the appropriate sections at the expected rate. They will check to make certain New Horizons is still in "encounter mode," which is scheduled to run through Thursday (July 16).

"It's just various housekeeping things that will tell us the health of the craft," Bowman said.

Pluto's best portrait

If New Horizons sent its message immediately after its closest approach, the update would already have arrived. But the spacecraft didn't do that, because it cannot simultaneously gather data and send communications back to Earth. (Doing so would require a more mobile antenna, which would increase costs. Having more moving parts would also increase the chance that parts could break, mission team members have said.)

The mission team is prioritizing data collection. New Horizons will continue to take science data as it zooms past the dwarf planet, including images of the night side illuminated by its largest moon, Charon.

"We have a small amount of time to collect all this very valuable data," said New Horizons project manager Glen Fountain, also of APL.

Even the telemetry data delivered this evening will come only because the spacecraft will be appropriately pointed to send the message immediately after completing one of its science observations.

Bowman told Space.com that, despite the rush to capture as much scientific data as possible, the team wants to know the spacecraft made it through the flyby OK. As a result, they were willing to sacrifice some of their time to confirm the status of the craft.

"We're taking a little bit of their science," she said.

After New Horizons completes a science activity known as a "plasma roll," in which several instruments measure the environment of Pluto, the probe's antenna will point back toward Earth for a brief 15-minute window. If a problem on the ground keeps the team from receiving the signal, the spacecraft won't keep broadcasting.

"You have such a short period to establish contact, and then it turns away," Bowman said. "Contact is not that long."

The signal will come "whether we're ready for it or not," Bowman said. "After that, [New Horizons] is going off to take science."

Down time

For the scientists and engineers involved with New Horizons, the window of time between the last communication Monday night (July 13) and the brief message tonight might seem like a good time to appreciate the ride.

"I told the team they really need to enjoy the time," Fountain said. "It's a wonderful time to be alive and to be aware of what's going on, to realize that you're part of something much larger than yourself."

But for most, if not all, of the team, the silence will be anxiety-inducing, despite confidence that the spacecraft should pass safely through the system.

"We are crossing all our fingers and toes," said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate.

According to Chris Hersman, system engineer for New Horizons, the team won't be tracking the spacecraft with the Deep Space Network. In part, this is because the craft shouldn't be transmitting under any circumstances. He also said he was told that if the antennas track the craft, listening to nothing, they can drift, keeping them from being on target when New Horizons establishes contact again. [Communicating With Deep Space: How It Works (Video)]

"It will be intense, but we're planning for success," Bowman said.

All quiet?

New Horizons reached the most dangerous part of its journey within 12 minutes of closest approach, New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver, of APL, told Space.com.

At that point, it passed through the equatorial plane of Pluto, where debris lost by the dwarf planet's moons has likely gathered. Collision risks are therefore highest in that region.

But if the ground team hears silence tonight, that doesn't necessarily mean bad news. According to Bowman, setting up the connections with the ground can be a challenge. A misconfiguration could explain any silence at the anticipated time.

"Even if we didn't get any contact at all, I'd be really scared, but I wouldn't jump to do anything because [the problem] could be on the ground," Hersman said.

Weaver said another opportunity to check the craft's status will come at 4:45 a.m. EDT (0845 GMT) tomorrow, when the team begins to receive the long-awaited images.

"If you get that data, you know we're cool," Weaver said.

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, said that simulations have shown that New Horizons has only a 2 in 10,000 chance of a destructive collision. It's a possibility, but not a strong one.

"I'm not losing any sleep over it," Stern said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky