Gravity-Mapping Satellite Swoops In for Closer Look

It's already made the most detailed map yet of Earth's gravity fields, but the GOCE satellite isn't done yet: Now it's lowering its orbit and coming closer and closer to Earth to make an even better map.

The data from the GOCE satellite, which is run by the European Space Agency, is enormously useful to scientists like geologists and climatologists and to oil companies and government officials. Measurements from the satellite have been used to visualize what is going on beneath the Earth's surface. The satellite has helped track the underground movement of lava and detect changes in gravity caused by melting glaciers, and it has produced the first high-resolution map of the boundary between Earth's crust and mantle.

But by lowering its orbit from 158 miles (255 kilometers) high to 146 miles (235 km) — which is about 310 miles (500 km) lower than most Earth observation satellites — the satellite is likely to produce an even more accurate map, the ESA says. The satellite is descending by about 980 feet (300 meters) a day and is slated to reach its new orbit in February.

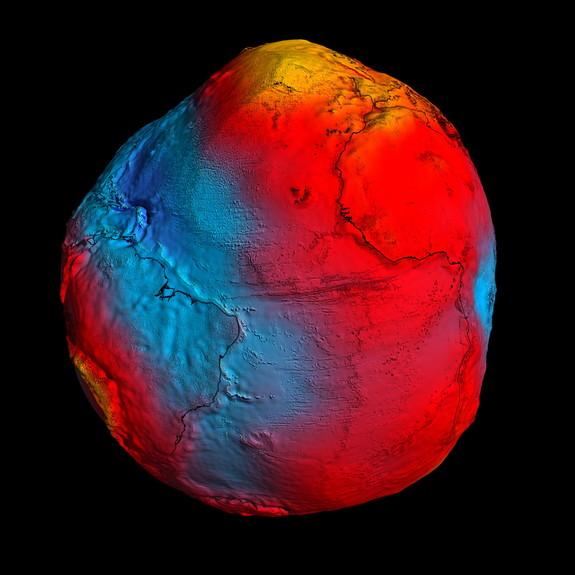

The maps produced by the satellite show the "geoid" of the Earth, a hypothetical surface around the planet at which the planet's gravitational pull is the same everywhere. Anything with mass has a gravity field that attracts objects toward it. The strength of this gravity field depends on the mass of the body. Since Earth's mass isn't spread out evenly, its gravity field is stronger in certain areas than in others. The strength of Earth's gravity varies depending on the depth of an ocean trench or height of a mountain, as well as the density of material.

Over dense areas, where gravity is stronger, the geoid moves away from the real surface of the planet, and where gravity is weaker, the geoid moves closer to the real surface. Mapping this geoid helps to conduct precise measurements of ocean circulation, sea-level changes and the mass of polar ice sheets, according to an ESA news release.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, sister site to SPACE.com. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

OurAmazingPlanet was founded in 2010 by TechMediaNetwork, which owned Space.com at the time. OurAmazingPlanet was dedicated to celebrating Earth and the mysteries still to be answered in its ecosystems, from the top of the world to the bottom of the sea. The website published stories until 2017, and was incorporated into LiveScience's Earth section.