The Sun's Strange Shape Revealed

In a strange twist of solar physics, the shape of our sun is rounder than previously thought, yet at the same time, it is also flatter — or squashed — more often, making the star wider at the middle than at its poles, scientists say.

The findings, announced today (Aug. 16), raise new mysteries about activity in the interior ofthe sun, researchers added.

The sun goes through rhythmic changes in activity. During these approximately 11-year-long solar cycles, the number of sunspots on the surface of the sun can rise and fall dramatically.

What shape, our star?

Until now, astronomers had presumed the shape of the sun changed along with this cycle. The flow of matter in the sun's interior and atmosphere is thought to shift over time due to the tumultuous magnetic activity accompanying the solar cycle, which in turn would transform the sun's shape.

"So far, just about anything we measure with sufficient accuracy about the sun ends up varying with the 11-year sunspot rhythm," study lead author Jeffrey Kuhn, a physicist and solar researcher at the University of Hawaii in Pukalani, told SPACE.com. [Photos: Views of the Sun from Space]

Still, for more than 50 years, researchers have found it quite challenging to measure the sun's shape.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There are literally tens of measurements, and most of them don't agree," Kuhn said. "Most of the differences are attributable to how hard it is to see small shape changes through the atmosphere."

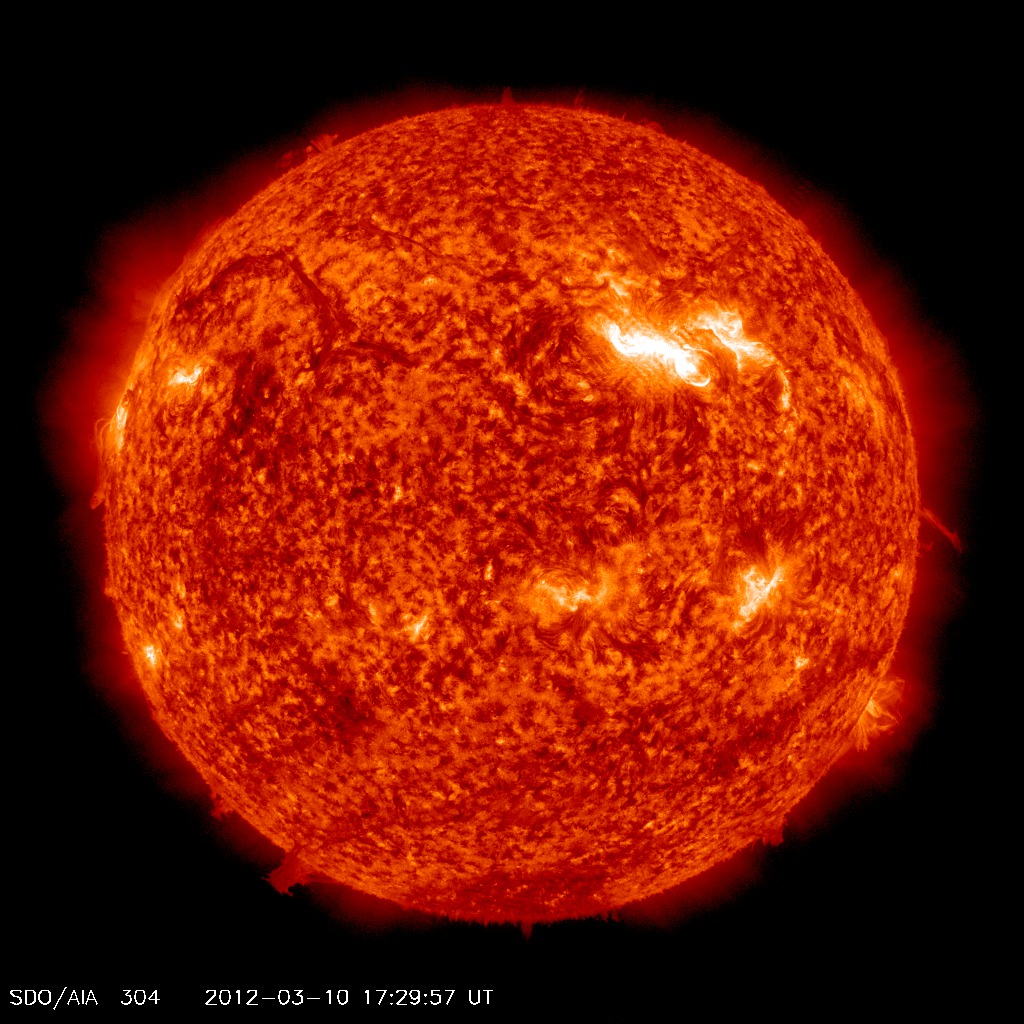

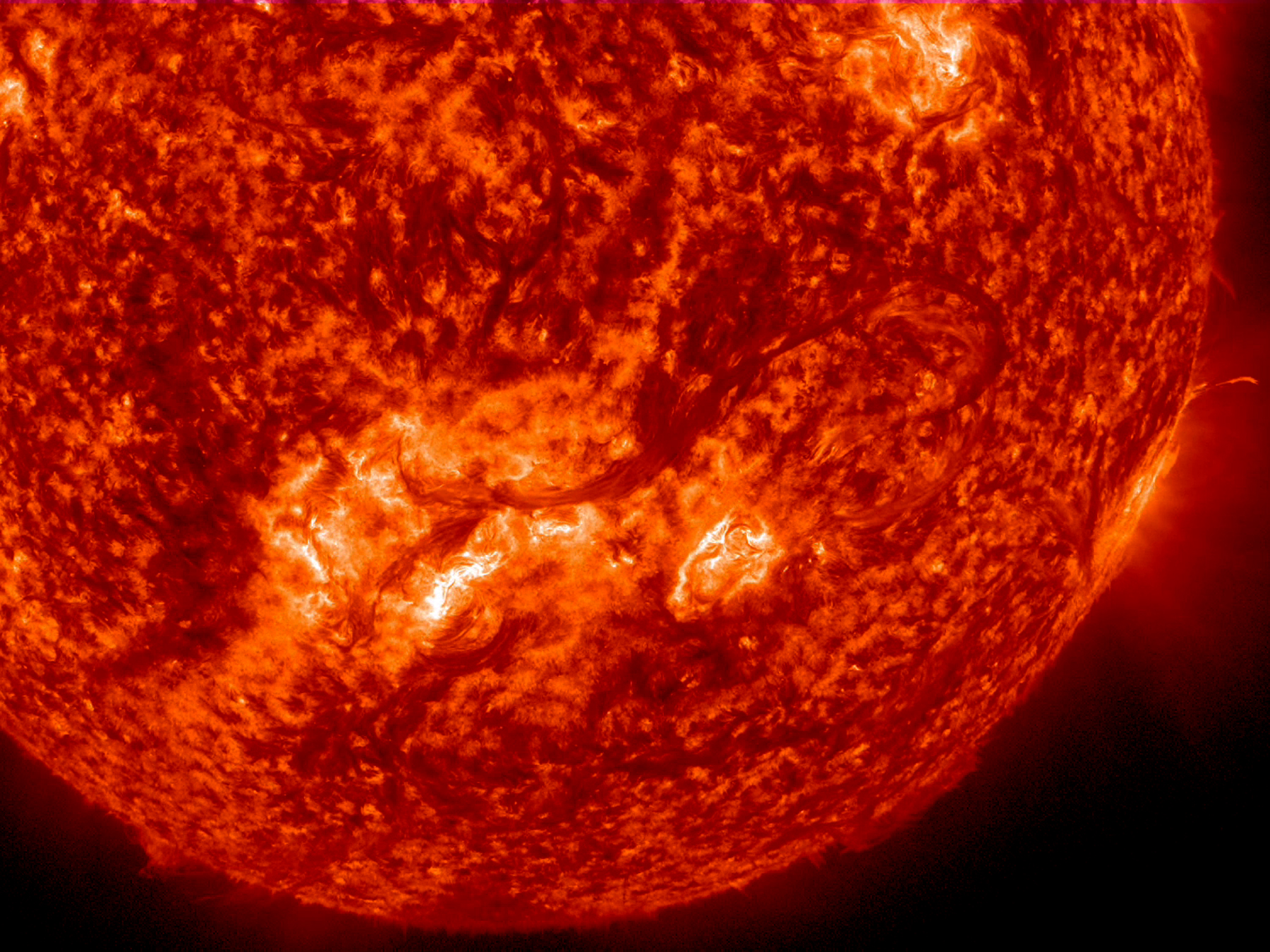

Now, using data from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, researchers measured the solar shape over a two-year period from 2010 to 2012, during which the sun evolved from a minimum of sunspot activity to a maximum. This observatory is in space, which helps it avoid the distorting influence that Earth's atmosphere can have on measurements of the sun's shape.

"Now that we have the necessary accuracy to measure the shape, it turns out it doesn't vary," Kuhn said.

Our flatter sun

Against their expectations, Kuhn and his colleagues found that the sun's slightly flattened shape — with a wide equator and a shorter distance between its poles — is remarkably stable and nearly completely unaffected by the solar cycle. This suggests the shape of the sun "really is controlled by fundamental properties of the star, and not so much by the sun's perhaps superficial magnetism, which is highly variable," Kuhn said.

However, while the sun is slightly flattened, its shape is still rounder than theory had predicted, researchers added.

"The peculiar fact that the sun is slightly too round to agree with our understanding of its rotation is also an important clue in a longstanding mystery," Kuhn said. "The fact that it is too round means that there are other forces at work making this round shape. We've probably misunderstood how the gas turbulence in the sun works, or how the sun organizes the magnetism that we can only see at the surface. Finding problems in our theories is always more exciting than not, since this is the only way we learn more."

Future research to measure the sun's shape more accurately can also help analyze how oscillations from deep in the sun's interior are manifested at its surface. "This will be a new and powerful tool for understanding why the sun changes, and how it will affect the Earth in the future," Kuhn said.

The scientists detailed their research online in the Aug. 16 edition of the journal Science.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us