The Legend of Rongo Rongo

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

We had just landed in the Juneau, Alaska airport--our last sign of what is called "civilization" for a while. Juneau is the only state capital that one cannot get to by road; one either flies or boats in. Along with colleagues Dr. Brenda McCowan of UC Davis, and Jeremy Crandell of PlanetQuest, we walked toward one end of the airport and outside to encounter what might best be described as an "Indiana Jones" - type airplane. It was a biplane on pontoons below which were retractable wheels. We were flying to the small Native American Tlinket village called "Angoon", there to meet up with colleagues from the Alaska Whale Foundation and Sean Hanser of UC Davis on their research vessel, the "Evolution". I actually got to sit in the co-pilot's seat as the pilot needed someone with a strong arm to retract the wheels by hand soon after we took off.

We had come to study the humpback whales, specifically to record their social and working vocalizations--they may be the most complex in the animal kingdom. We have recordings of humpbacks that sound just like wolves howling, monkeys barking, dolphins whistling, cows mooing, lions roaring, elephants trumpeting, and even humans talking, along with numerous additional bubbling, gurgling, screeching, groaning, and burping sounds unique to their own repertoire.

One of our projects was to record humpback whales in the presence of boat noise and compare it with their vocalizations in the absence of boat noise in order to determine if boat traffic could be interfering with their feeding and social behavior. For this we were using hydrophones and information theory analysis software we had developed based on Shannon Information Theory--the mathematics of quantifying how much information is being sent across a given phone line. Usually used to quantify how much information is being sent through computer lines these days, we instead just assume that Chatham Strait itself is a communication channel and that the humpbacks are sending information to each other at rates that might vary with and without background noise.

I, of course, was interested in the generalized communication complexity of the whole animal kingdom for the purpose of formulating general rules for application to any possible SETI (search for extraterrestrial intelligence) signals that may someday be received. However, being in the presence of working humpbacks certainly helped give me a sobering notion about any possible other species on another planet. When a couple of dozen humpback whales surface one is inexorably led to consider how really alien their world is compared to our own daily lives.

Unlike the humpbacks in Fredrick Sound, for example, which generally eat krill (which they just guide into their open mouths), the humpbacks in Chatham Strait go after herring, which can swim faster than the humpbacks can. But they have a trick--that must certainly qualify for bona fide tool-making. They coordinate with sounds, and some individuals start to make a net of bubbles while another (or others) start to herd the herring in the direction of this cylindrical net of bubbles. Timing is crucial as the net, being made of bubbles, is rising toward the surface all the time. The herring are herded into the net, and the humpbacks come up underneath with their mouths open. Each humpback mouth can hold a bit more than about a moving van's worth of water and fish. It is an unforgettable experience to see them break the water with huge gulps and trumpeting exhales.

In addition, from mitochondrial DNA analysis done by Dr. Fred Sharp and Pieter Folkens of the Alaska Whale Foundation, these fishing groups (up to two dozen) are not directly related to each other. This is of interest as it may represent the only other long-term non-familial associations beside humans, i.e., humans associated in given professions. "Try outs" for the fishing team have been observed, and one can hear when the bubble net has been successful or not. The vocalizations proceed for a while, then one hears a rise in tone, and then one looks for a huge amount of bubbles, followed by fish flying out of the water, followed by huge great open mouths breaking the water. Once a fishing party is formed, they always come up--all two dozen fifty-ton animals--the same way, time after time. They all know their place in the fishing scheme.

When one hears these vocalizations but then right in the middle they stop, a bubble net has not been built correctly, or a herder has not done their job correctly, and the herring have gotten away. This is followed first by a slow rising of the humpbacks followed by a whole bunch of vocalizations. One could almost imagine that they are arguing about who messed up and why. Following this behavior it has also been observed that one or two big humpbacks fill their mouths with water (to be big) and push an individual or two away from the pack, excluding them from participating in the bubble net fishing group. Then they head back down again and the whole process starts over.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

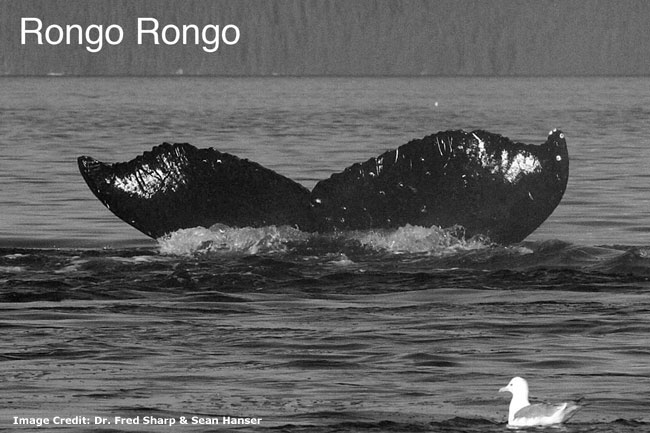

The Alaska Whale Foundation has a catalogue of over 500 individual humpback whales, identified by tail fluke (but after a season one can tell them also by their vocalizations). Each has a name--Melancholy, Beethoven, Taylor, etc. While on the boat we were talking about information theory a lot, and we had recently applied it to the analysis of the undeciphered and only past written language of Polynesian, known as "Rongorongo." Using information theory we had discovered something about the characters in Rongorongo that might be helpful in its interpretation. It was thus that when a brand new humpback whale showed up this last season that the Alaska Whale Foundation folks decided to name the newcomer, "Rongo Rongo." He has quite a unique fluke design - almost two "W"s (with a bit of imagination) on each fin (see picture).

So I guess it is a bit early to tell yet if Rongo Rongo will become a legend or not. But he was the first new humpback whale to show up while we were applying information theory to humpback vocalizations. And who knows? He may turn out to make a major contribution to the analysis and possible decipherment of an extraterrestrial signal someday. For now he is honing his fishing skills--trying out for the bubblenetters guild, no doubt--and joining his colleagues in making the most diverse sounds in the animal kingdom. I look forward to seeing and hearing him next season. And it may be that we'll find out that humpbacks and humans are not so alien to each other after all.

Laurance Doyle is a principal investigator for the Center for the Study of Life in the Universe at the SETI Institute, where he has been since 1987, and is a member of the NASA Kepler Mission Science Team. Doyle’s research has focused on the formation and detection of extrasolar planets. He has also theorized how patterns in animal communication, like those of social cetaceans, relate to humans.