Japan Calls it Quits on Infrared Space Telescope

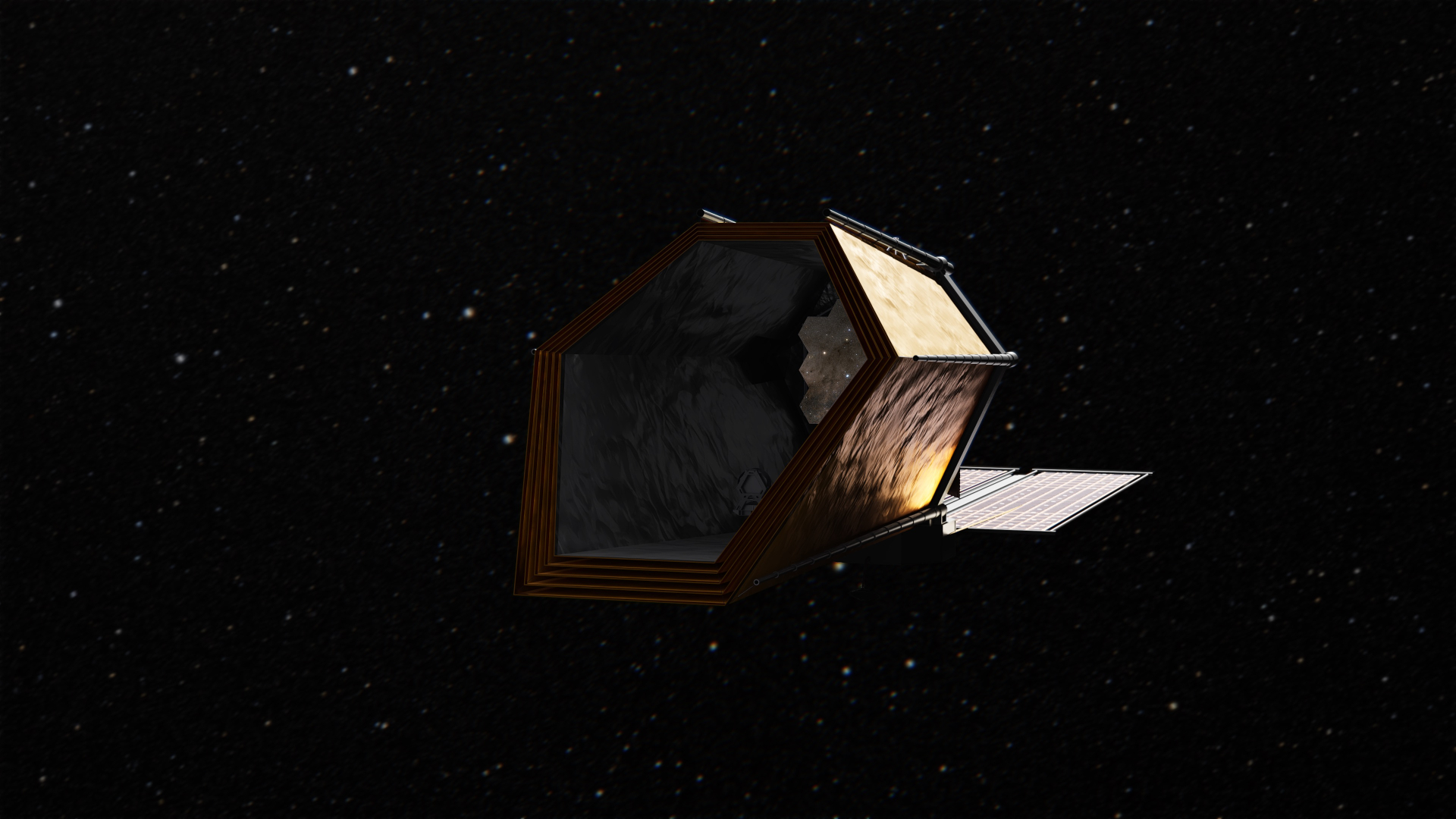

Japan announced last week that its Akari infrared space telescope was switched off after five years of scanning the sky in search of star-forming dust clouds, ancient galaxies in the distant universe, and asteroids within the solar system.

The Akari mission succumbed to trouble in its power generation system, which first appeared in May and ended the satellite's scientific observations in June.

The observatory stopped receiving electricity on the night side of its orbit around Earth, an indication its batteries were not charging sufficiently. The craft remained powered in sunlight.

The anomaly appeared May 24 when Akari shifted to a low-power mode and haulted science observations. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, or JAXA, concluded the problem was probably within the satellite's electrical system.

In a written statement released in English on Friday, JAXA said it turned off Akari's transmitters at 0823 GMT (3:23 a.m. EST) on Nov. 24. Akari was in an extended phase of its mission, which surveyed the sky in near-infrared and far-infrared light. It was Japan's first infrared space telescope.

Akari launched in February 2006 on an 18-month primary mission. A vat of super-cold liquid helium kept Akari's 27-inch telescope and scientific payload chilled to minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit, or just above the point of absolute zero. [Infographic: Giant Space Telescopes of the Future]

The liquid helium ran out in August 2007, putting the observatory's most sensitive far-infrared instrument out of business. But Akari continued its mission with near-infrared camera observations made possible by mechanical coolers aboard the satellite.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Akari, which means light in Japanese, was operating beyond the three-year design goal of the mission when the power problem appeared in May.

Japan led the mission with the support of the European Space Agency, which provided a ground station in Sweden for daily communications with Akari during the prime mission in 2006 and 2007.

ESA also helped process data streaming back to Earth from Akari. In exchange, European astronomers obtained 10 percent of observing time with the telescope.

Universities in Japan, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and South Korea participated in Akari data reduction.

"Akari provided infrared source catalogues containing 1.3 million objects as well as many essential outcomes in the infrared astronomy," JAXA said in a press release.

Akari's two sensors observed at wavelengths between 1.7 and 180 microns, according to JAXA.

The mission's infrared instruments could peer through thick, cool veils of dust to observe stellar nurseries, where matter collects and ignites to form baby stars. Akari also peered deeper into the cosmos to see other galaxies and uncovered hard-to-find asteroids and forming planets closer to home.

Most infrared light does not penetrate Earth's atmosphere, so researchers must launch telescopes into space to see the infrared sky.

Akari's mission was to study a population of objects for detailed follow-up observations by more powerful telescopes. Such a survey allows astronomers to classify and create statistical analyses of celestial bodies, leading to a better understanding of the formation and evolution of galaxies, stars and planetary systems.

It was the first all-sky infrared survey since 1983. NASA's WISE telescope completed a more sensitive scan of the universe in 2010.

Copyright 2011 SpaceflightNow.com, all rights reserved.

Stephen Clark is the Editor of Spaceflight Now, a web-based publication dedicated to covering rocket launches, human spaceflight and exploration. He joined the Spaceflight Now team in 2009 and previously wrote as a senior reporter with the Daily Texan. You can follow Stephen's latest project at SpaceflightNow.com and on Twitter.