Back to the Moon: How New Lunar Bases Will Work

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This story was updated at 12:26 p.m. ET, Jan. 19.

It's been nearly 40 years since people last set foot on the moon, but momentum is building for a return to Earth's nearest neighbor — and for the establishment of a permanent manned presence on lunar soil.

The moon harbors large amounts of water ice, along with lots of other potentially useful compounds. These resources could theoretically support manned lunar bases, which could serve as staging grounds for further exploration of the solar system, and as proving grounds for outposts on Mars.

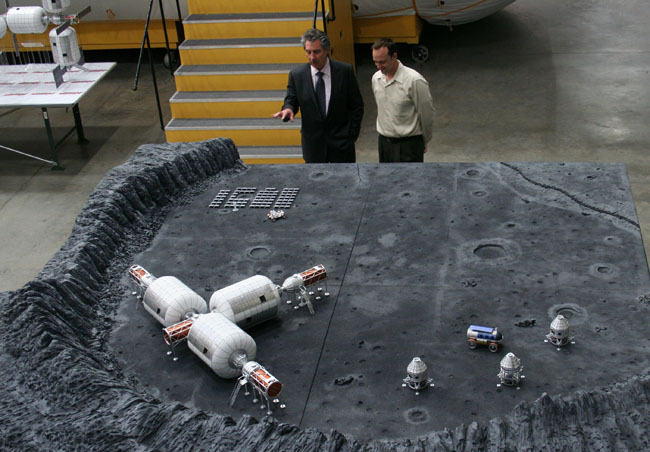

But if we do set up lunar bases, what will they look like? How will they function? NASA scientists have been working on these questions, as have folks in the private sector who see loads of money to be made on the moon's frigid surface.

Suffice it to say that any future operation would look very different than past lunar missions. After all, the first humans to walk on the moon — Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin — spent only 21 hours on the lunar surface in July 1969. The last people on the moon — Apollo 17’s Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmidt — stayed for just over three days in 1972.

A 21st-century moon base, on the other hand, would be expected to operate for months or years at a time.

NASA's vision: Mobile robot convoys

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

With the cancellation of the moon-bound Constellation program last year, NASA's focus has shifted away from returning to the moon and toward visiting asteroids and Mars.

But the agency is still fleshing out plans for a moon base, which would be a cooperative effort between robots and humans. And calling it a base is perhaps misleading, since the entire enterprise would be very mobile.

The idea is to send bots and astronauts up together — at first, likely to Shackleton crater near the moon's south pole, said Matt Leonard, deputy project manager for lunar surface systems at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Getting to the poles requires less fuel than other moon destinations, Leonard said, and the area in and around Shackleton — a 12-mile-wide (20-kilometer-wide) crater whose floor is in perpetual shadow — looks to have lots of water ice.

The first few human crews would stick around for a week, then a few weeks, then a month — gradually building a presence at Shackleton, performing research and gaining knowledge about how to live and work on the moon, Leonard said.

The robots that would assist these crews would likely include the 176-pound (80-kilogram) K10 scouting rover, along with the All-Terrain, Hex-Limbed, Extra-Terrestrial Explorer (ATHLETE) — a six-legged, heavy-lift cargo carrier. The Space Exploration Vehicle (SEV), an updated version of Apollo's old "moon buggy," would also chip in.

Astronauts would drive around in SEVs, which are pressurized with air, meaning they can sit inside them without wearing their bulky space suits. The SEV has pivoting wheels, allowing it to move sideways as well as forward and backward. And unlike the open-air moon buggy, the SEV is protected from radiation by thick shielding.

After a few crewed missions had come and gone, the machines would decamp from Shackleton by themselves and head for Malapert Massif, a ridge about 81 miles (130 kilometers) away.

Engineers on Earth would drive the bots, Leonard said, though the machines would be smart enough to pick their own path at least part of the way.

"We might leave some science sensors behind, but for the most part we'd take everything with us," Leonard told SPACE.com. The ATHLETEs would carry big loads like the astronauts' living and working quarters, as well as heavy equipment.

About six months after the robotic convoy sets out, another astronaut crew would meet up with it at Malapert, and the cycle would begin again. Robots would move around the moon's southern half, doing scouting and scientific survey work for astronauts, who would rendezvous with them at various spots.

"We'd just keep kind of leapfrogging around to sites that are interesting," Leonard said. "We'd try to work ourselves up toward the equator."

The basics of the mobile base

As they moved around the moon, astronauts would live and work in habitat modules. The current design for such quarters is a rigid cylindrical structure about 16 feet (5 meters) wide and 11 feet (3.3 m) tall, according to NASA officials. These modules can link together to form large, interconnected complexes.

NASA is also considering inflatable habitat modules, which would pack very tightly aboard a launch vehicle but expand greatly in space or on the lunar surface, potentially providing astronauts with much more room. The agency is planning to test a hybrid module — a rigid one with an inflatable structure atop it — this year at Desert RATS, its annual series of field trials in the Arizona desert, Leonard said.

Because the moon has virtually no atmosphere, the lunar surface is often blasted with dangerous levels of radiation. To shield astronauts, the habitat modules might be put in lava tubes underground or buried in the lunar soil, Leonard said.

Moon dirt would help keep astronauts alive in other ways, too. Astronauts could bake water out of it, and from the water they could separate out hydrogen and oxygen. These two materials are the chief ingredients of rocket propellant, allowing moon dwellers to fuel up for trips home or to Mars.

Lunar soil contains lots of other stuff, too, like silicon. So astronauts could even start building things on the moon, such as solar panels, from local resources.

This level of self-sufficiency is a few years down the road, though, Leonard said.

"In the first eight years we'd bring all of our logistics with us that we would need," he said. "But we'd bring those production plants down with us right away. As soon as they're up and running, our logistics train is a lot smaller and we can do a lot more exploration."

At the moment, NASA is planning to power most of these prospective bases with solar energy, Leonard said. However, agency scientists are also looking at alternatives such as fuel cells and nuclear power, which have definite advantages.

"Obviously,nuclear would make you much less light-sensitive," Leonard said. "If we went in that direction, we might arrange our missions in a different way."

The private sector: mining bases

NASA's mobile bases would be research operations. But some people are looking to set up lunar outposts as a way to make money.

The Shackleton Energy Co., for example, wants to mine the moon's water ice and turn it into rocket fuel. Shackleton Energy Co. (SEC), which was formed in 2007, would sell the propellant from fueling stations in low-Earth orbit (LEO).

Because spaceships burn so much fuel just lifting off from Earth, letting them top up in orbit could spur a huge wave of travel and discovery in space, according to SEC founder Bill Stone. And it makes sense to supply the filling stations from the moon, since it's about 15 times cheaper to launch something to LEO from there than from Earth, Stone added.

"In our view, the moon is a stepping stone," Stone told SPACE.com. "What we extract from there will enable the exploration of the inner solar system."

SEC's mining bases would likely be at one or both lunar poles, in craters whose frigid depths have trapped lots of water over the past several billion years. Craters like Cabeus, perhaps, where water ice makes up 5.6 percent of the lunar dirt by weight.

Like NASA's outposts, SEC's bases would rely heavily on machines.

"This will be a man-tended, mostly robotic operation," Stone said.

The robots would include scouting rovers, likely developed using NASA's experience and technology as a guide, Stone said. Heavier machinery would perform the water-ice extraction, which would basically consist of heating, after which lunar soil would be put back in place.

Six to eight people might oversee the mining operations in any one location, according to Stone. Initially, these crews might have to stay for a year, but future base dwellers would likely sign on for six-month stints. These crews would live in inflatable habitat modules.

Human-tended robots would perform most of the mining, transportation and processing of water ice into fuel. The processing step would take place up in LEO, where huge shipments of water would be converted to rocket propellant, Stone said.

Unlike NASA, SEC is absolutely set on its energy source.

"We have to have nuclear power," said SEC president Dale Tietz. Solar just won't cut it, since the company needs to work extensively in and around dark crater bottoms that can be as cold as minus 396 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 238 Celsius).

The rovers would be powered by radioisotopic thermoelectric generators, Tietz told SPACE.com. RTGs convert the heat generated by the decay of radioactive substances like plutonium into electricity. To keep its habitat modules warm and to power its industrial operations, SEC would rely on nuclear reactors, Tietz said.

Coming soon?

SEC has received lots of interest from investors and is making steady progress, according to Stone. The company intends to send robotic scouting missions to both poles within four years, Stone added, with sales of propellant in LEO following shortly thereafter.

"By the end of the decade, there's a high likelihood we'll be up and running," Tietz told SPACE.com.

SEC may not be the only private enterprise operating on the moon in 10 years or so. Bigelow Aerospace is considering setting up lunar bases, too. Bigelow designs and builds inflatable space habitats, and SEC may well get its modules from Bigelow, Stone said.

Bigelow has already deployed two prototype inflatable modules in space, and last year the company signed deals with six clients interested in using the structures

For a possible moon base, Bigelow envisions using its BA-330 modules, so named because they offer 330 cubic meters of usable internal volume. Several of these, along with propulsion tanks and power units, would be joined together in space and then flown down to the lunar surface.

After piling some lunar dirt over the habitats — to protect against micrometeorite strikes, thermal extremes and radiation — clients could move into the ready-made moon base, using it for whatever they wished.

"We've had it partially designed for five or six years," said Robert Bigelow, the company's founder. "From all aspects, it looks very doable."

Bigelow said he thinks the private sector may get people back on the moon by early in the next decade. If that happens, it could be the prelude to even bigger things.

"We can use the moon as a pathfinder," Bigelow told SPACE.com. "It's the perfect ground to get our feet wet for Mars."

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.