Best Time to Observe the Moon This Month is Now

The next few nights are the best time this month to observe the moon with binoculars or a small telescope.

Tonight (Jan. 12) the moon will be just past first quarter. This means that the sun’s light will be falling on the moon from the right, causing very oblique lighting all across the center of the moon’s disk, the boundary between sunlight and shadow known as the terminator.

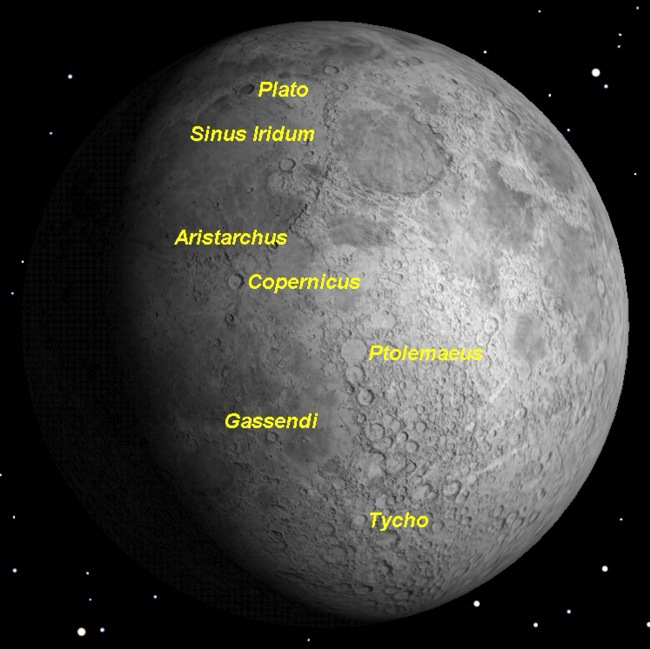

This map of the moon's craters shows some of the best natural landmarks to look for when observing the lunar surface.

In a small telescope, or even in binoculars, the easiest crater to see is the huge ring plain almost in the center of the moon’s disk, Ptolemaeus. This gigantic crater, 95 miles (153 km) in diameter, is named for the greatest Greek astronomer of ancient times, Claudius Ptolemy, who lived in the second century. [Gallery: Our Changing Moon]

Look also for the perfectly oval crater Plato close to the moon’s north pole. This crater is 63 miles (101 km) in diameter and named for the famous Greek philosopher who flourished in the fourth century B.C.E.

Because of the moon’s rapid movement around the Earth, the direction of the sun’s light changes greatly from one night to the next, making the study of the moon a constantly changing show. By tomorrow night (Jan. 13), the terminator will have moved westward. Ptolemaeus will be harder to see, though the dark floor of Plato continues to make it well-defined. New craters will be lit by the rising sun, such as Copernicus, near the center of the disk, and Tycho, near the moon’s south pole.

These craters are named for two astronomical "greats" of the 16th century.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Copernicus, 58 miles (93 km) in diameter with terraced walls, is named for the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who placed the sun at the center of the solar system. Tycho, 53 miles (85 km) in diameter, center of the moon’s brightest system of rays, is named after Tycho Brahe, the Danish astronomer who was the most accurate observer of his time.

By Friday night, the sun will be penetrating farther westward, bringing into sunlight the graceful curve of the Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows) on the north shore of the Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains).

These fanciful names were given to these features in the 17th century, before we knew that the moon was a barren, airless world. To the north, the walled plain of Gassendi is a striking crater. The crater, 68 miles (110 km) in diameter, is named for Pierre Gassendi, a 17th century French astronomer.

Saturday night the sun will illuminate the crater Aristarchus. Although smaller than many craters at just 25 miles (40 km) in diameter, Aristarchus is one of the youngest and brightest craters on the moon. It is named for Aristarchus of Samos, third century B.C. Greek philosopher, the first to correctly place the sun in the center of the solar system.

One of the greatest treats for an amateur astronomer is watching the moon’s terminator sweep majestically across the face of the moon — and this is the perfect week to do that.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.