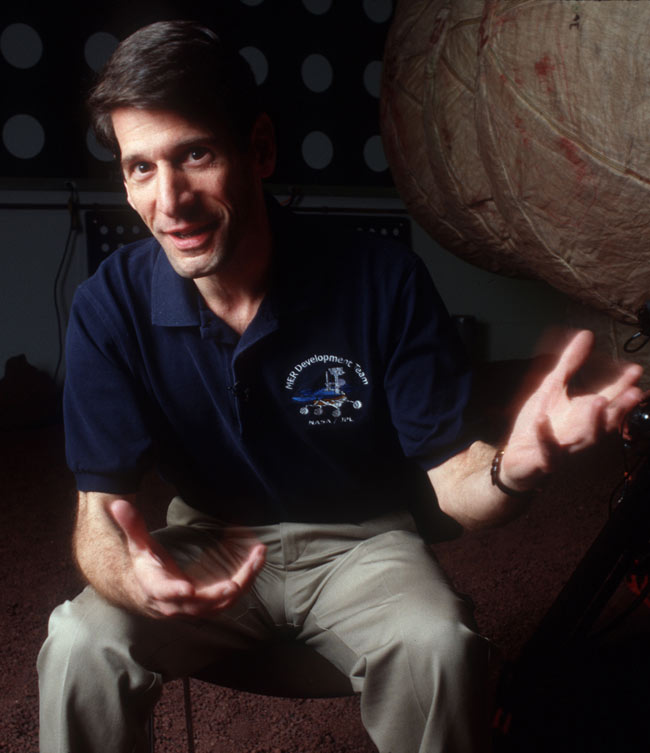

Making Mars a Familiar Place: Q and A With Mars Rover Manager John Callas

The NASA rovers Spirit and Opportunity landed on Mars in January 2004, on a three-month mission to search for clues about past water activity on the Red Planet.

The twin golf-cart-size rovers delivered big, finding lots of evidence that Mars was once a much wetter and warmer place. And the six-wheeled robots just kept chugging along, way past warranty.

Nearly seven years later, Opportunity is still going strong, though it has been driving backward for about two years to spread wear more evenly within its gear mechanisms. Spirit got bogged down in soft sand last year, and the rover stopped communicating with Earth in March 2010. [Mars Rovers: 7 Years on the Red Planet]

Between them, the two rovers have covered more than 21 miles (33 kilometers) of the Martian surface and taken about 250,000 pictures, according to Mars Exploration Rover (MER) project manager John Callas, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

SPACE.com caught up with Callas in mid-December, at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, to chat about what the rovers have accomplished, how they've changed our perception of the Red Planet — and whether Spirit is ever going to wake up.

SPACE.com: Are you surprised that the rovers have lasted so long — that we're talking about what they're up to now, nearly seven years after they landed on Mars?

John Callas: Oh, absolutely. I joined the mission during the development phase, back in 2000. We were saying, "Oh, it's a 90-day mission. Maybe if we're lucky, we'll get 120 days on the surface." Some of the wild thinkers said, "Oh, maybe we'll get 180 days on the surface of Mars."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But the fact that, seven years later, they're still going — that's just remarkable. And now the question is, How long can they go? We've gone 26 kilometers with Opportunity. How far can this rover really go?

SPACE.com: Do you have any guesses about that? It was supposed to go 1 kilometer, and now it's at 26.

Callas: You know, it's almost that we haven't got a clue at this point of how far they can go. Because it was designed for 1-kilometer mobility. Spirit had a wheel failure early on, after only a few kilometers, and so we were thinking, "Is this an indication that all the wheels on all the rovers are going to fail now?"

But Opportunity has been extremely well behaved. We were able to mitigate the problems we saw with one of the wheels drawing a little bit more current. But it's the kind of thing that, at any moment they could just blow out on you with no warning whatsoever.

Maybe it's kind of like a set of tires on your car. Maybe they're getting a little old, a little bald, but you keep driving on them. And then one day, Boom! You get a blowout, and that's it. So every day's a blessing that we can go with these vehicles.

SPACE.com: What are the prospects for Spirit? Are you optimistic that it will warm up and wake up, now that we're into the Martian spring?

Callas: It's a tough situation for the rover. And it's also tough for the team, because we have such a strong emotional attachment. This is kind of like having a loved one who's in a coma. And your hope is that they'll wake up from the coma and they'll recover, but each day that goes by, the prospects and the likelihood diminish a little bit.

And so the reality that we haven't heard from the rover so far, now that we're in Martian spring, it's concerning. And then each day that goes by, it's one more tick downward in our optimism for the rover.

SPACE.com: If and when you conclude that Spirit is gone for good, will there be some sort of ceremony at JPL? Will you mark the rover's passing with a funeral or something?

Callas: Well, that's a good question. I like to think it would be a celebration of the great accomplishments that Spirit has made. Spirit found the evidence for these hydrothermal systems, for example. Not only was there liquid water on Mars, but there were energy sources coincident with that liquid water. So you have a system that could potentially support an ecosystem.

Think of geysers in Yellowstone, or deep ocean vents, which are thriving living systems here on Earth. We know those kinds of physical conditions existed on Mars. That's one of the great discoveries that Spirit made.

And it actually made that discovery as a result of its right front wheel failing, because we would drag that wheel. As we drag that wheel, it cuts a furrow in the ground, revealing what's just beneath the surface. We would've just driven right over this place and never noticed it. But the wheel unearthed that material, and it really significantly changed our thinking about Mars.

SPACE.com: So how have Spirit and Opportunity changed our understanding of Mars?

Callas: Well, the scientists can tell you more about the details of the discoveries the rovers have made. But for me, these rovers have rewritten the history books for Mars. One of the great intangibles is that, in addition to all the scientific discoveries, these rovers have made Mars a familiar place. Mars is now our neighborhood.

My team at JPL, and the scientists at all the supporting institutions, go to work on Mars every day. And we look at the images that we see from the rover, and we see familiar sights. The rim of Endeavour crater now is a familiar sight to us. Seeing the rover tracks left behind as the rover drives — that's familiar now. So Mars is our neighborhood.

SPACE.com: The rovers have brought Mars close, making it more accessible. We are now in constant contact with robots on another planet — that's really amazing.

Callas: That's right. I hear from the rovers more frequently than I hear from some of my siblings.

SPACE.com: How have Spirit and Opportunity paved the way for future missions? Mars Science Laboratory [MSL, slated to land on the Red Planet in August 2012] will build on what these two rovers have done, right?

Callas: Yes. It's important to remember that these rovers are part of a program of Mars exploration — not only landers and rovers, but orbiters as well, and they work together. The orbital spacecraft make great contributions to enriching the science that the surface vehicles can do.

And early missions benefit late missions. Clearly, we're learning a lot about how you operate a roving vehicle on the surface of another world, and that plays into how they'll operate MSL. Specifically, our rovers have been doing things like advancing and proving out technologies that MSL will use.

The new flight software on the rover that has all of this autonomy was tested on our rovers, and that's going to be the baseline for the flight software that Mars Science Laboratory will use.

We have a new technique called Aegis, which is a way of autonomously collecting science data, where we don't have ground in the loop. The rover actually looks through its images, finds targets of interest, and then uses the high-resolution imagery to take additional pictures of those targets. That software is going to be baseline for MSL as well.

Many of the same people that worked on the MER rovers are working on the MSL rover. Many of the people who are on my team are also supporting MSL. So a lot of the corporate knowledge and experience base will transfer to MSL, and to other future missions.

SPACE.com: You've had to troubleshoot some with Opportunity — it's been driving backward for the last two Earth years or so. If something does bring Opportunity down, what do you reckon it'll be?

Callas: Well, that's really tough. What could kill the rover? You could have a component fail inside the rover that's catastrophic. The rovers are single-string, meaning that there's no redundancy in the electronics. So any one essential piece failing could result in the loss of the rover.

That said, even if Opportunity were to lose its mobility, for example — we could do what we're planning for Spirit. If we hear from Spirit again, even though it may be a stationary rover, there's still important science we can do as a lander. When the rovers stop moving, they then become the best fixed Mars landers that have ever flown onto the planet. [Gallery: Latest Photos From Spirit and Opportunity]

So there's a whole suite of scientific investigations we can do using the rovers as landers. One of the exciting ones is, just by tracking the radio signal from the rover — because the rover's now fixed to the surface, the motion of the rover now becomes a proxy for the rotation of the planet.

So we can measure the precession and nutation [slight wobbling] of the spin axis of Mars very precisely, which tells us about the distribution of mass within the core. So we can figure out how big the core is. And if we see a slosh, we can tell whether it's a solid or a liquid core, and that would be a really, really key finding for Mars.

SPACE.com: Are you proud to be associated with the rover program, which has accomplished so much?

Callas: Oh, yeah. How could I not be? This is clearly the most exciting point of my career. This is arguably one of the most successful missions of robotic exploration that humankind has ever undertaken. It's been wildly, wildly successful. We've made so many significant discoveries.

You think about the discoveries about surface water, hydrothermal systems on Mars and evidence not only for ancient water, but perhaps for more recent water on Mars. To be there, to be the person that first sees these images, these vistas that no one else has seen before — like the first to stare into Santa Maria crater, for example. It's really been a privilege, and very exciting, to be a part of this mission.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.