Apollo Astronaut Study Reveals Greater Heart Risk for Deep-Space Travelers

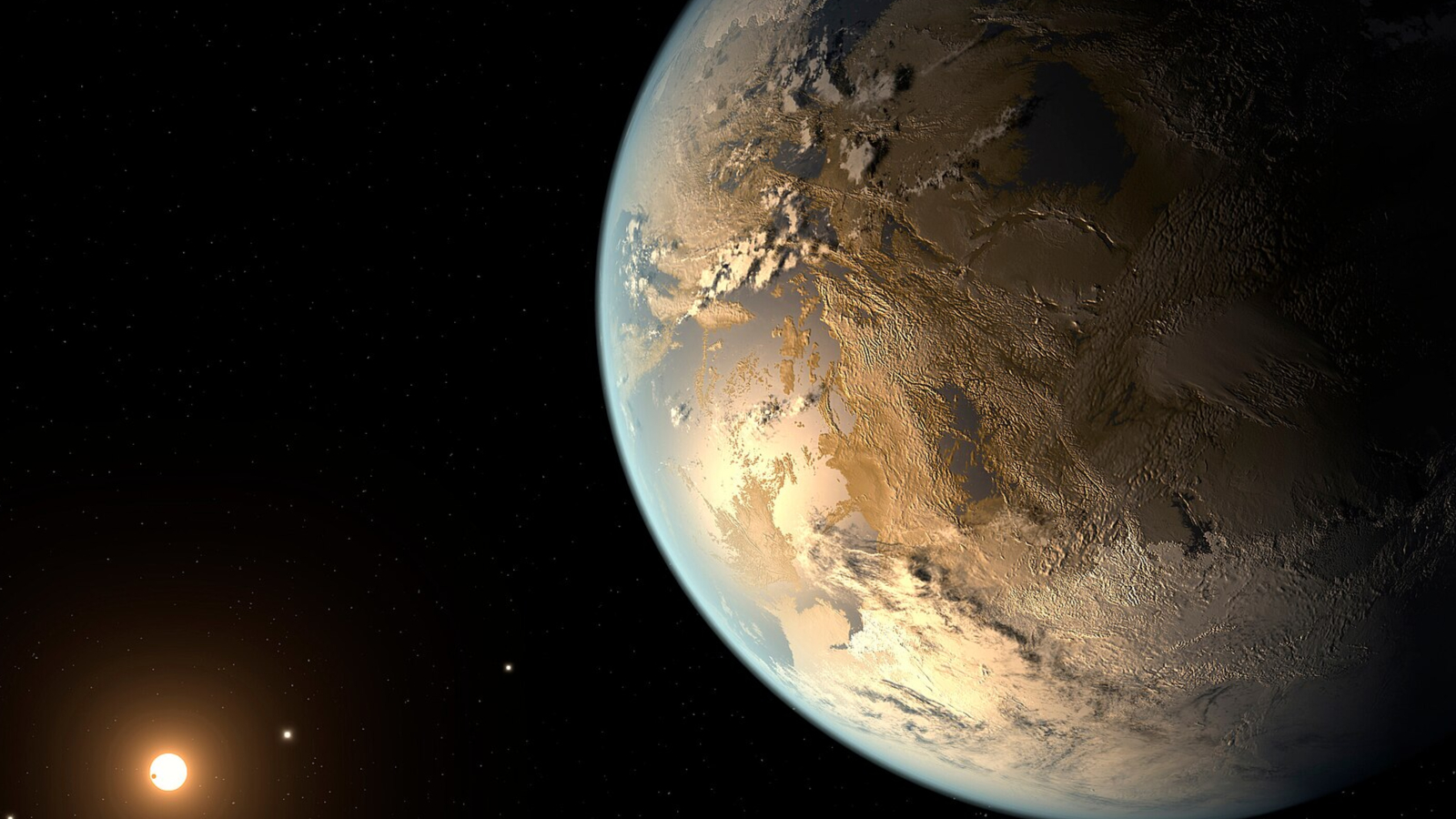

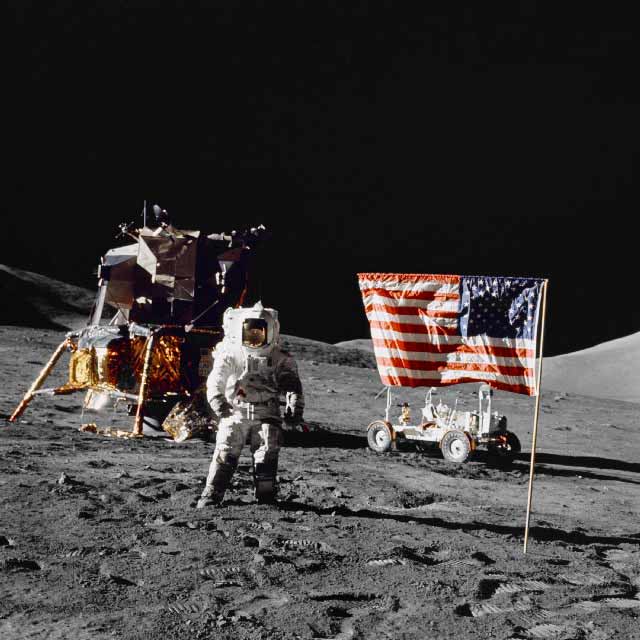

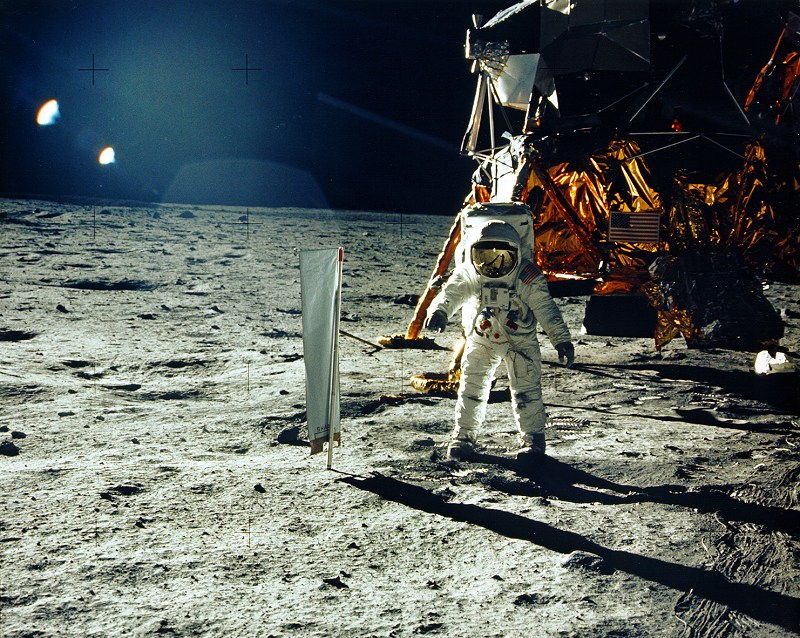

NASA astronauts on the Apollo missions to the moon, flown in the 1960s and 1970s, are the only humans to have flown beyond the protective magnetic shielding of Earth — and a new study shows that exposure to deep-space radiation may have taken a toll on their hearts.

The research compared Apollo astronauts' fates with those of unflown astronauts — who never made it into space — and those who lingered in low-Earth orbit, and found an increased level of death from cardiovascular problems in the deep-space adventurers. In a study with mice, the researchers also found a long-term effect on heart health from radiation exposure.

The International Space Station is scheduled to be decommissioned in 2024, and nations (and private companies like SpaceX) are turning their sights to the moon and Mars, said Michael Delp, a researcher at Florida State University and lead author of the new study. And with that comes exposure to deep-space radiation, which we know little about. [The Human Body in Space: 6 Weird Facts]

"With deep-space radiation, really, the 24 Apollo astronauts that went to the moon are the only astronauts that have really been exposed to this, because all the others — cosmonauts and astronauts — have stayed in low-Earth orbit," Delp told Space.com.

While there have been a few previous studies looking at astronauts' causes of death, this was the first to compare astronauts with other astronauts rather than the general population, Delp said — the study's control population included astronauts assigned to Apollo, Gemini and space shuttle missions that were ultimately canceled, among others. Those astronauts were selected but never made it to space, so they should have the same baseline health as those that did. (The researchers selected unflown astronauts who were chosen at close to the same time as the Apollo astronauts, Delp said, and although the astronauts who stayed in low-Earth orbit were selected slightly later, the ages at death for all the astronauts considered were comparable.)

"This was really the first indication that travel into deep space might have some health consequences, particularly on the cardiovascular system," Delp said.

Delp's group considered seven Apollo astronauts, 35 later astronauts who reached low-Earth orbit and 35 astronauts who never flew, and found that the proportional deaths due to heart disease were equivalent for the astronauts who never flew and the ones who stayed in low-Earth orbit, but for Apollo astronauts those deaths were four to five times more common. (Three out of the seven died from cardiovascular disease.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers also tested mice exposed to similar radiation as well as simulated weightlessness on Earth: Mice exposed to either radiation or weightlessness all showed injury to blood vessels and arteries, which could lead to heart attacks and strokes, and those exposed to both showed even more damage. Six to seven months later, though, which Delp said was the equivalent of 20 human years, only the ones exposed to radiation showed sustained harm to their blood vessels.

"I think it poses a really interesting hypothesis," said Richard Hughson, a cardiovascular physiologist at Schlegel-University of Waterloo Research Institute for Aging who was not involved in the study. "Delp and his group teased out this data, had a hypothesis, tested it with the mouse model, and showed some fascinating long-term effects of radiation on endothelial [blood vessel cell] function," he told Space.com.

Hughson and others have studied the impact of spaceflight on heart and blood vessel health, but have found that the mechanisms affected by low-Earth orbit mostly recover normal function post-flight — these radiation effects, on the other hand, seem to linger. To directly investigate the effect in humans, he said, it will be important for future astronauts to test their own blood vessel function once on the moon.

Going forward, Delp said, researchers need to look at the minimum radiation to have a harmful effect, examine the mechanism behind it and begin to explore countermeasures to lessen the radiation's effects — shielding is one option, but there could be other actions to take to protect the body. Delp also plans to collaborate with the Johnson Space Center to study the Apollo astronauts' medical history in more depth.

"Most scientists have felt like it would take years of being exposed to space radiation before there would be any harmful effects, and what this study does is it shows that even about two weeks of exposure may be causing harmful effects," Delp said. "It doesn't prove that radiation is doing it, but it's indicating that we probably need to do more research and look at this more carefully than we have in the past."

"It's really the first step, or first glimpse, into how deep space may be affecting human health," he added.

The new work was detailed today (July 28) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Editor's Note: A new NASA statement, posted the afternoon of July 28, discusses the agency's astronaut health research and states that the data used in the observational portion of this study is too limited to determine cosmic rays' impact on the Apollo astronauts. At this article's press time, NASA had not responded to multiple requests for comment.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.