Gravitational Waves: Spying the Universe's 'Dark Side'

The Feb. 11 announcement that scientists had, for the first time, proof that space itself vibrates is expected to unleash a bevy of discoveries about things that go bump in the proverbial darkness.

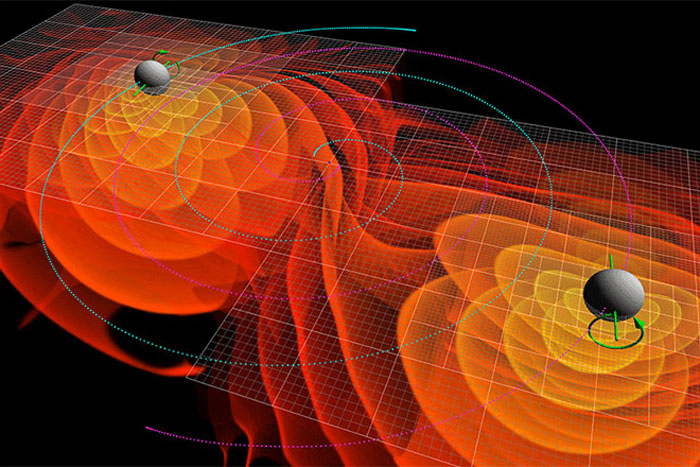

The initial detection of so-called gravitational waves occurred in September when a pair of black holes, each about 30 times more massive than the sun, spiraled in toward each other and then merged into a new, larger black hole more than 1.3 billion light years away.

PHOTOS: What You Need to Know About Gravitational Waves

In a flash, the crash released the equivalent of 50 times the energy of all the stars in the universe, powerful enough to ever-so-slightly jiggle L-shaped, 2.5 mile-long laser beams on Earth that comprise the heart of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO.

LIGO observatories in Louisiana and Washington had just been upgraded when the detection was made. Scientists spent months verifying the gravitational waves' footprint, which changed the length of the laser light arms an amount 10,000 times smaller than the diameter of a proton. Meanwhile, LIGO continued to monitor for other space-shaking cosmic booms.

"Before this, we didn't even know that black holes existed in pairs," University of Florida physicist David Reitze, now serving as LIGO director at the California Institute of Technology, told the House Science Committee last week.

"It's the start of a new astronomy," added Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicist David Shoemaker.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The LIGO detectors collected data for another three months, then shut down to prepare for an even larger boost in sensitivity.

NEWS: Gravitational Waves Detected for First Time

Additional findings have yet to be released, but Louisiana State University physicist Gabriela González, a spokeswoman for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, hinted to legislators that the detection of the merging black holes was not a solitary event.

"We saw one event in one month … so we can only predict from that data. But we have taken data for three more months, which we are still analyzing and everything that we see is consistent with what we saw there," Gonzalez said.

From theoretical models, scientists expect to be able to detect at least a few gravitational wave events per year, she added.

Merging black holes aren't the cosmic events likely to vibrate the fabric of space and time.

Scientists are hopeful that LIGO will sense the rumblings of neutron stars, which are the dense remnants of collapsed stars so packed with matter that a single teaspoon would weigh 10 million tons.

Typically, neutron stars are magnetized and spinning, though how that works is not fully understood. They also can exist in pairs, giving scientists an opportunity to detect not only gravitational waves set off by their interactions, but X-ray, radio waves and other electromagnetic radiation they produce.

ANALYSIS: We've Detected Gravitational Waves, So What?

"We can put together all this information … and know more than we could have ever known without gravitational waves or without this combination, this synergy of information," Shoemaker said.

LIGO also may be able to ferret out supernova explosions, collapsing stars, cosmic strings and even what Shoemaker calls "defects" in the interwoven fabric of spacetime.

"There certainly will be surprises. Every time we open up a new window to the universe, we see new things," Shoemaker said.

By the time LIGO returns to work late this summer or early fall, it may be joined by the first of several planned laser interferometers outside the United States.

Virgo, a French- and Italian-backed project, located near Pisa in Italy, will add a third ear to detect and verify gravitational waves and pinpoint their source.

Virgo also will serve as a backup if either of twin U.S. LIGO detectors is offline. Having at least two simultaneous detections is key to being able to rule out possible terrestrial sources of vibrations.

100 Years of General Relativity: Thought and Action

Japan is developing a gravitational wave detector as well, and last week the Indian government gave its approval to move ahead with the LIGO-India project.

Europe also is testing a space-based gravitational wave detector called LISA Pathfinder.

"In space, instead of having 2.5-mile long arms (to detect gravitational waves), you can have 2.5-million mile long arms. Our sensitivity grows with the length of those arms," Shoemaker said.

Since gravitational waves, like electromagnetic radiation propagate at different lengths, scientists expect that multiple gravitational wave observatories will be needed to study different phenomena.

"We are looking at the dark side of the universe, about which we know very little," Gonzalez said.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Irene Klotz is a founding member and long-time contributor to Space.com. She concurrently spent 25 years as a wire service reporter and freelance writer, specializing in space exploration, planetary science, astronomy and the search for life beyond Earth. A graduate of Northwestern University, Irene currently serves as Space Editor for Aviation Week & Space Technology.