Tiny satellites use AI to sniff for methane leaks on the ground (photos)

Emissions of potent greenhouse gas methane significantly contribute to climate change.

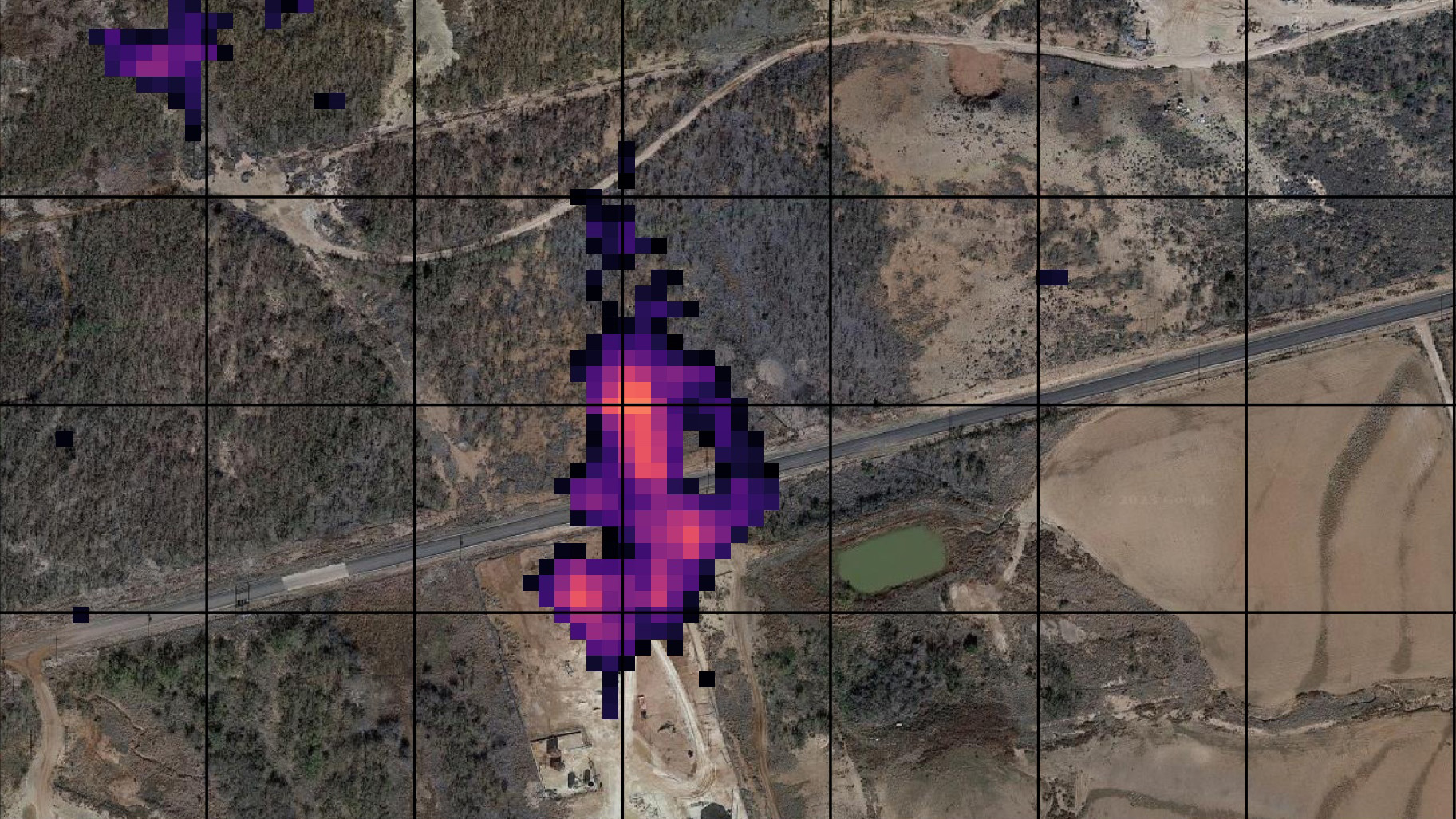

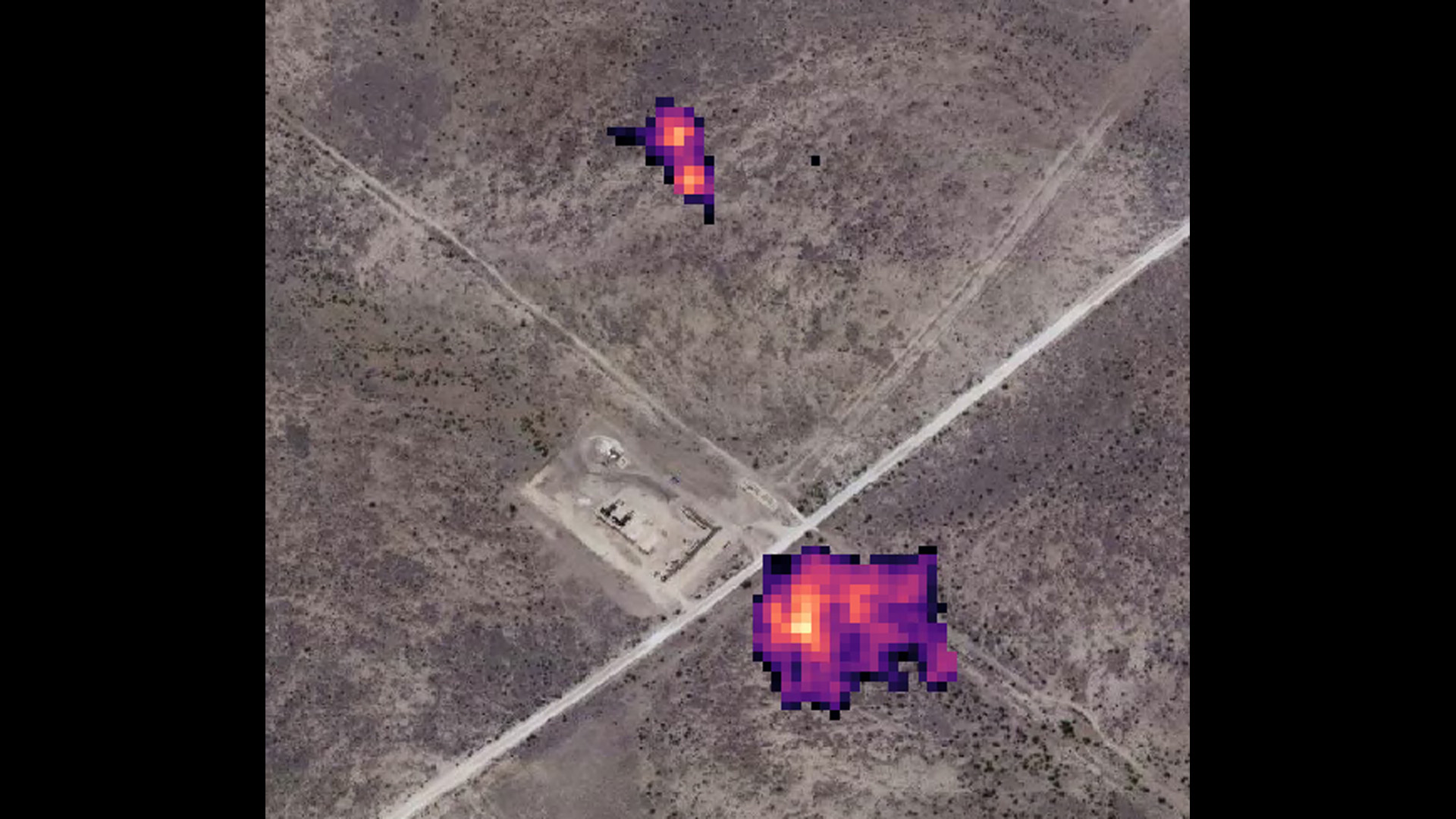

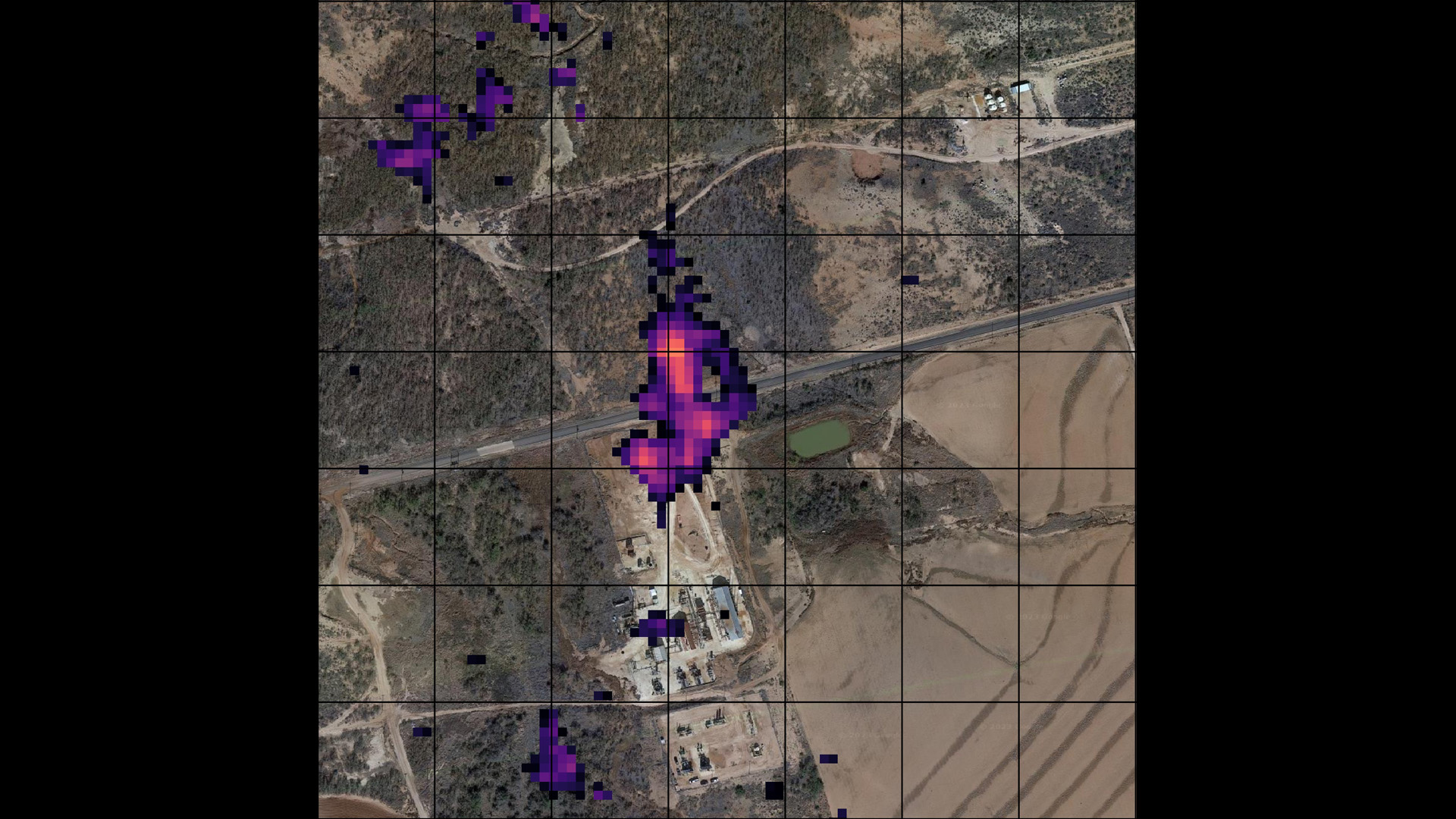

California-based Earth-observation startup Orbital Sidekick has released the first images from its new constellation of planet-watching satellites that promise to take methane-leak monitoring from space to a new level with the help of AI.

Orbital Sidekick's three satellites, launched earlier this year, are fitted with hyperspectral sensors that analyze 500 bands of light across the electromagnetic spectrum. Hyperspectral imaging offers 20 times better sensitivity compared to other systems currently in orbit, the company said in a statement. This sensitivity enables Orbital Sidekick to "chemically fingerprint" Earth's surface with a resolution of 26 feet (8 meters), revealing sources of contamination in unprecedented detail.

Orbital Sidekick said that, among other applications, the technology will help improve detection of methane leaks from space. Methane is the second most common greenhouse gas found in Earth's atmosphere after carbon dioxide, accounting for 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions (compared to carbon dioxide's 76%), according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. But methane has an outsized impact on Earth's climate: It's more than 25 times more potent as a warming agent than carbon dioxide is.

Related: New satellite to police carbon dioxide emitters from space

Over the past few years, several companies have begun measuring methane levels from space, with the aim of helping reduce emissions of this greenhouse gas.

At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, also known as COP26, world leaders pledged to focus on reducing methane emissions in a bid to slow down climate change. A considerable proportion of these emissions comes from oil and gas pipelines and rigs and is completely preventable. Imagery by satellites, such as those operated by Orbital Sidekick, can help companies stop those leaks early.

Orbital Sidekick described its images as offering "higher resolution" and being "much more advanced" than those provided by older satellite systems.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

AI algorithms run by the satellites' onboard computers analyze the measurements in orbit and beam down to Earth information about hotspots with high methane concentrations, indicating potential leaks.

"With our initial datasets, we’re able to analyze the chemical composition of each pixel and have started building out our proprietary spectral library," Orbital Sidekick said in the statement. "We’re building one of the most robust remote sensing analytics capabilities that will assist us to understand the dynamic nature of our planet on a chemical level."

In the future, Orbital Sidekick wants to expand the use of its data to help farmers with precision agriculture and to assist disaster responders and security forces. The company plans to launch three additional satellites next year.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.