Surprisingly mature galaxy in the infant universe suggests galaxies form faster than we thought

"This galaxy looks like a grown adult, but it should just be a little child."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A distant galaxy in the newborn universe essentially resembles a grown adult when it should just look like a small child, new findings that suggest galaxies may evolve far more rapidly than previously thought.

Galaxies come in a variety of shapes, colors and sizes. Much remains a mystery about how galaxies formed in the early universe and how they evolved mature features such as rotating disks and central bulges of tightly packed stars. To peer that far back in time, astronomers need to look at light from distant galaxies, but such targets are often too dim to see well.

In the new study, researchers focused on the galaxy ALESS 073.1,. The starlight they detected from this galaxy came from 12.5 billion years ago, when "the universe was 1.2 billion years old, about 10% of its current age," study lead author Federico Lelli, an astrophysicist at Cardiff University in Wales, told Space.com.

Related: Scientists think they've spotted the farthest galaxy in the universe

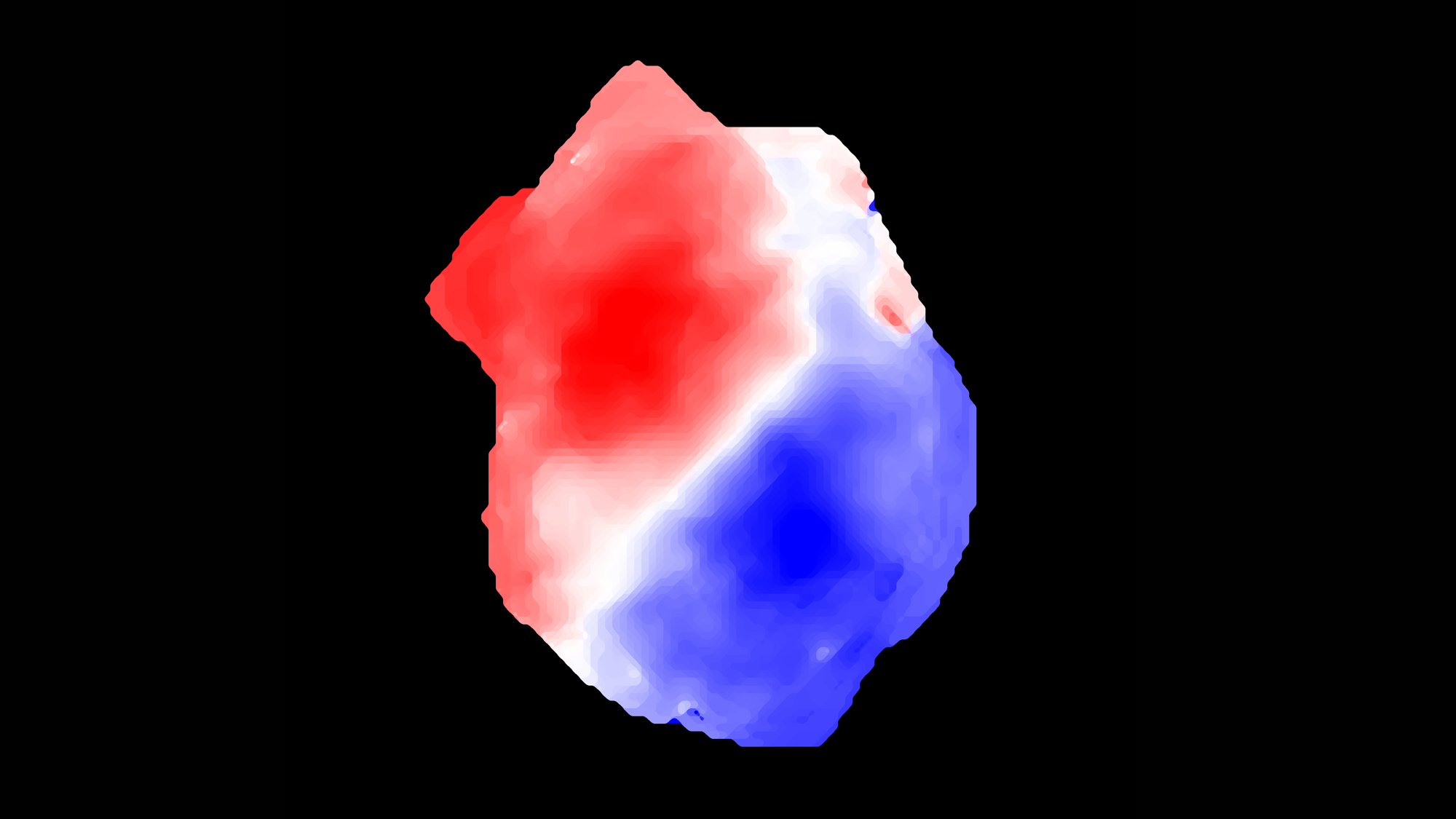

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the scientists analyzed high-quality images they successfully collected of ALESS 073.1's dust and gas. They used this data to model how matter was concentrated in the galaxy and calculate its motions.

Unexpectedly, the researchers discovered the galaxy possessed both a rotating disk and a central bulge. They also found signs it may even possess the same kind of spiral arms that mature galaxies such as the Milky Way have extending from their cores.

"This galaxy looks like a grown adult, but it should just be a little child," Lelli said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

ALESS 073.1's core also generated more energy than can be explained by stars. Prior work has suggested that such an "active galactic nucleus" (AGN) hints at the presence of a supermassive black hole millions to billions of times the mass of the sun.

Previously, researchers thought central bulges formed slowly over time, due to gravitational instabilities within a galaxy, or mergers between galaxies. "ALESS 073.1, instead, was able to form a big bulge, making up about half of its stars, in less than 1.2 billion years," Lelli said. "This young galaxy appears surprisingly mature."

Earlier research also suggested that galaxies forming in the primordial universe are generally expected to be chaotic, turbulent and largely unstructured because of all the activity they are going through, such as devouring gas from their surroundings and forming stars at very high rates. The orderly structure detected within ALESS 073.1 "is at odds with these expectations," Lelli said.

These new findings suggest that galaxies can form mature features such as disks and bulges far more quickly and efficiently than previously thought. "Structures like bulges, regular rotating disks, and possibly spiral arms must form in less than one billion years, which is a tall order for current models of galaxy formation," Lelli said.

In the future, the scientists aim to collect similar high-quality images for a dozen or so more galaxies from the same cosmic epoch, Lelli said.

"These new observations will establish whether galaxies like ALESS 073.1 are the rule or the exception in the primordial universe," Lelli said. "The observations were supposed to take place last year, but unfortunately the ALMA observatory was shut down due the COVID-19 emergency."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Feb. 12 issue of the journal Science.

Originally published on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us