Asteroid hit by NASA's DART spacecraft is behaving unexpectedly, high school class discovers

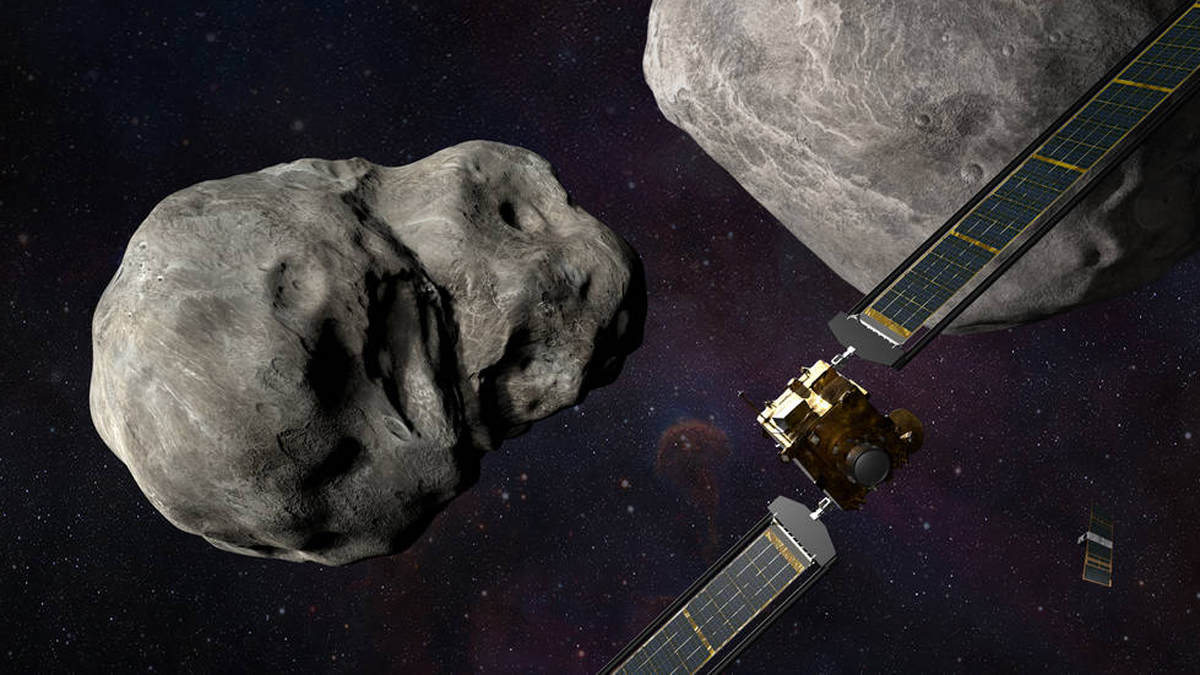

Asteroid Dimorphos, which NASA intentionally hit with a rocket during its DART mission in September 2022, is behaving in unpredicted ways.

The asteroid Dimorphos is behaving in unexpected ways after being hit with a NASA rocket last year, new data suggest.

Recent observations of the roughly 580-foot-wide (177 meters) space rock — which NASA intentionally crashed a spaceship into on Sept. 26, 2022, as part of the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission — show that Dimorphos may be tumbling in its normally steady orbit around its parent asteroid Didymos, according to New Scientist. Dimorphos also appeared to be continuously slowing down in its orbit for at least a month after the rocket impact, contrary to NASA's predictions.

California high school teacher Jonathan Swift and his students first detected these unexpected changes while observing Dimorphos with their school's 2.3-foot (0.7 meter) telescope last fall. Several weeks after the DART impact, NASA announced that Dimorphos had slowed in its orbit around Didymos by about 33 minutes. However, when Swift and his students studied Dimorphos one month after the impact, the asteroid seemed to have slowed by an additional minute — suggesting it had been slowing continuously since the collision.

"The number we got was slightly larger, a change of 34 minutes," Swift told New Scientist. "That was inconsistent at an uncomfortable level."

Related: Could an asteroid destroy Earth?

Swift presented his class's findings at the American Astronomical Society conference in June. The DART team has since confirmed that Dimorphos did indeed continue slowing in its orbit up to a month after the impact — however, their calculations show an additional slowdown of 15 seconds, rather than a full minute. A month after the DART collision, the slowdown plateaued.

What caused Dimorphos to slow steadily for a month, before reaching equilibrium? A swarm of space rocks could be to blame: Recent observations of the asteroid have revealed a vast field of boulders — likely shaken loose from Dimorphos' surface during the impact — strewn about the area. It's possible that some of the larger boulders fell back onto Dimorphos within that first month, slowing its orbit further than anticipated, DART team member Harrison Agrusa told New Scientist.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The DART team plans to release its own report on the unexpected findings in the coming weeks. However, complete answers may have to wait until 2026, when the European Space Agency's Hera spacecraft is scheduled to arrive at Dimorphos to investigate the cosmic crash site up close.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.