Titanic cosmic bubbles blown by the Milky Way are surprisingly complex

Astronomers have discovered new properties of the giant lobes of gas called eRosita bubbles that extend far out from the center of our galaxy.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

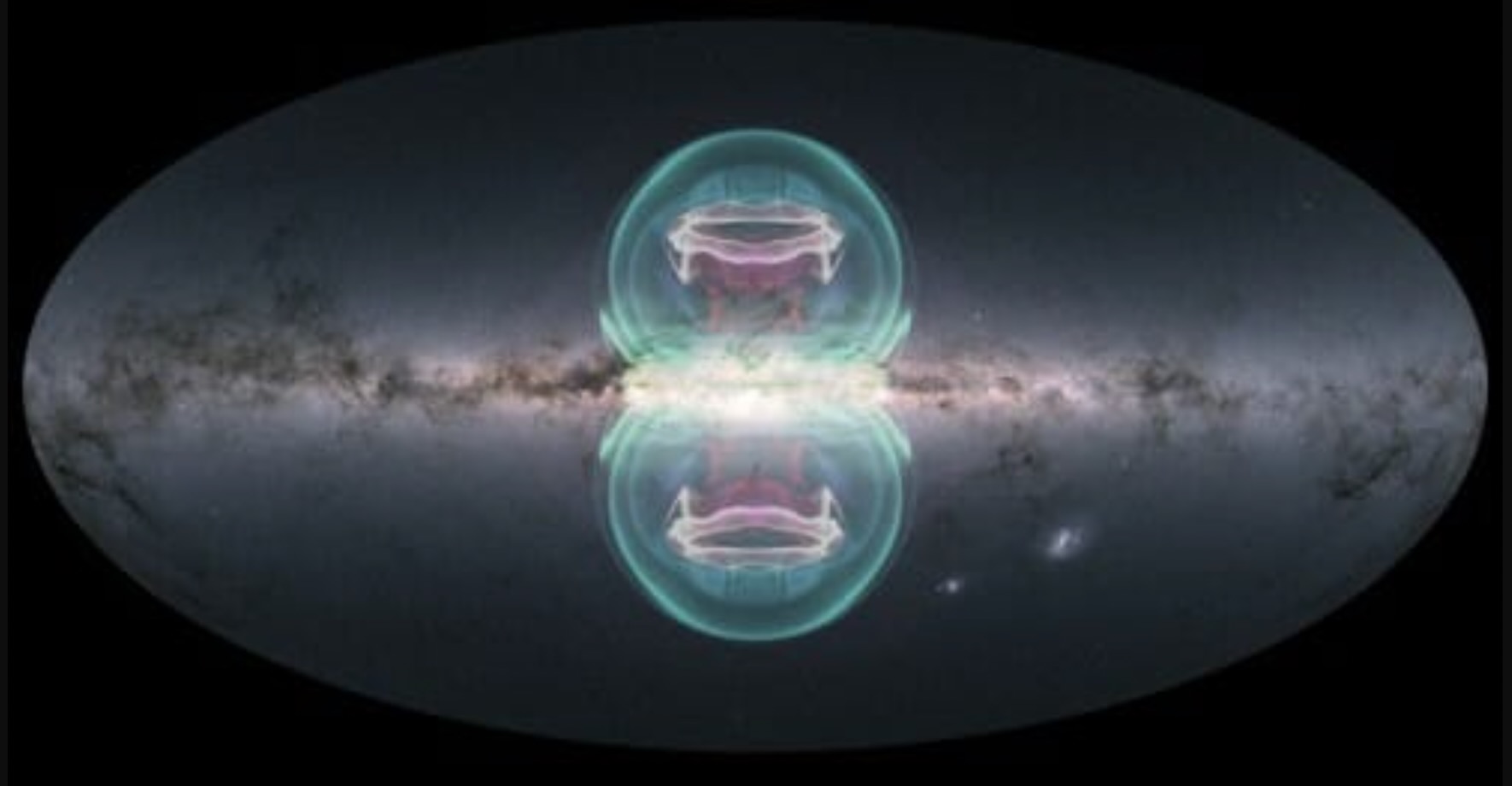

The giant bubbles of hot gas blown out from the center of our Milky Way galaxy are far more complex than previously believed, a new study suggests.

The discovery could finally explain how these 36,000-light-year-tall structures, which extend from the Milky Way's disk, are formed, scientists said.

The new study examined the thermal and chemical properties of these features, called eRosita bubbles, revealing hitherto undiscovered properties in their shells.

Related: Milky Way galaxy: Everything you need to know about our cosmic neighborhood

These bubbles — named after the eRosita X-ray telescope that first sighted them — aren't the only set of bubbles extending from the disk of the Milky Way. They are joined by Fermi bubbles, which, despite possessing a similar shape, are half the size of eRosita bubbles and are also less energetic than their larger counterparts.

These structures extend through the gas that surrounds our galaxy, known as the circumgalactic medium. Astronomers hope that the study of such bubbles sheds light on the process of star formation and helps explain how galaxies like ours come together.

"Our goal was really to learn more about the circumgalactic medium, a place very important in understanding how our galaxy formed and evolved," research lead author Anjali Gupta, a professor of astronomy of Columbus State Community College in Ohio, said in a statement. "A lot of the regions that we were studying happened to be in the region of the bubbles, so we wanted to see how different the bubbles are when compared to the regions which are away from the bubble."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While scientists had previously assumed that galactic bubbles are heated by shocks of gas pushed out from the Milky Way, Gupta and her team found, surprisingly, that the temperature of the gas within the bubbles is similar to the temperature of the gas outside them. The astronomers found that the eRosita bubbles are bright not because of their temperature but instead because they are filled with extremely dense gas.

Gupta and her colleagues reached their conclusion by examining 230 observations of eRosita bubbles made between 2005 and 2014. These observations characterized emissions from low-density gas from the bubbles and the hot gases around them.

Currently, scientists aren't sure about the origins of galactic bubbles; the topic is hotly debated in astronomy and astrophysical circles. Some scientists believe these bubbles are blown outward by activity centered around the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way, known as Sagittarius A*. The new research could help settle that debate, the team believes.

For example, abundances of certain elements in the bubbles suggests that they were first created by star-forming activity or the injection of energy from massive stars or other astrophysical processes, team members said.

"Our data support the theory that these bubbles are most likely formed due to intense star formation activity at the galactic center, as opposed to black hole activity occurring at the galactic center," team member Smita Mathur, an astronomy professor at Ohio State University, said in the same statement.

The team will continue to investigate the eRosita bubbles, further characterizing their properties and looking at the implications their current findings have on other aspects of astronomy by using data collected by new space missions.

"Scientists really do need to understand the formation of the bubble structure, so by using different techniques to better our models, we'll be able to better constrain the temperature and the emission measures that we are looking for," Gupta concluded.

The team's research was published this month in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.