Mars glaciers were slowed by fast drainage and weak gravity, scientists suggest

Mars may be a freeze-dried planet now, but once, it was supposedly (almost) another Earth, with flowing water that froze into hulking mountains of ice.

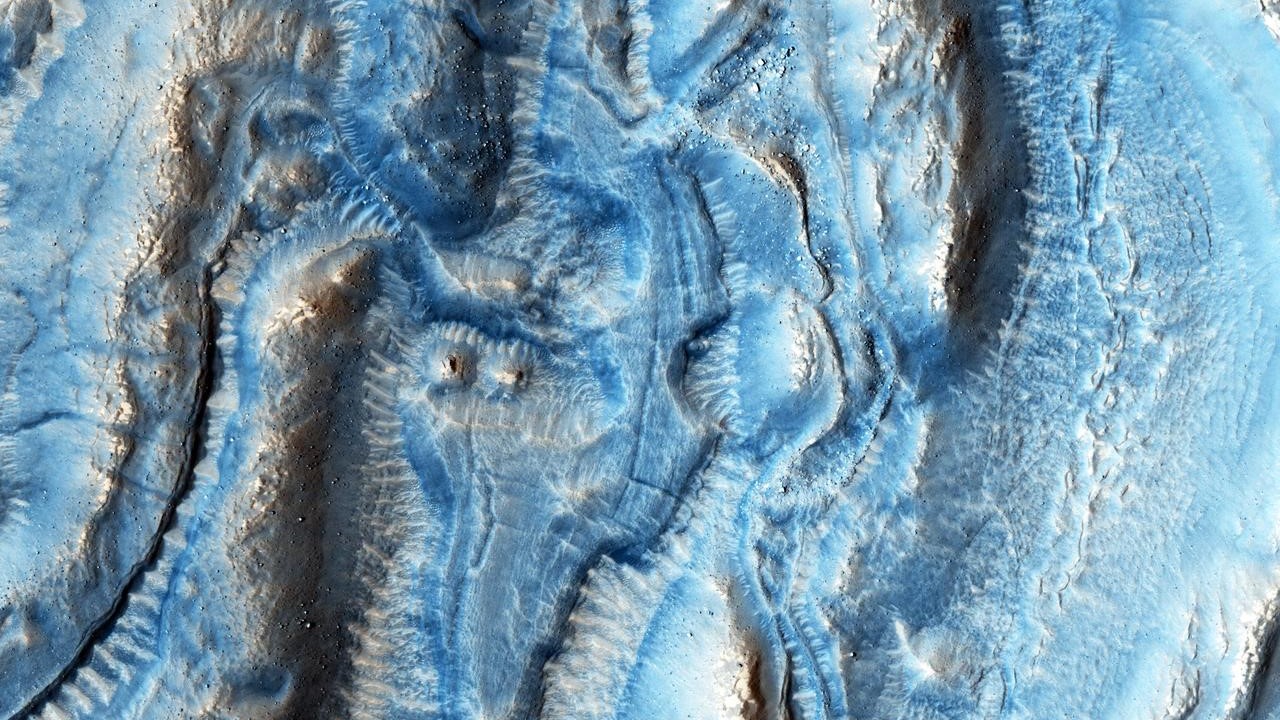

Because glaciers and ice sheets on Earth tend to slip and slide, they crawl across land and carve out stark geophysical features including linear grooves, ridges, and inverted hills. Scientists previously thought that glaciers on Mars stayed frozen in time due to the lack of similar features on the Red Planet. Planetary scientist Anna Grau Galofre of Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géosciences at Nantes Université in France led a study that found glaciers on Mars are on the move — they just happen to be extremely slow.

"On Earth, this glacial motion has produced scoured landscapes in northern Europe and North America," Grau Galofre wrote. "Mars lacks such large-scale glacial erosion even in areas with other signs of widespread glaciation."

Related: These dry ice glaciers on Mars are moving at its south pol

Instead, Martian landforms created by glacial melt and movement are mostly ridges and valleys with shallow, undulating channels. Scientists had previously assumed that Martian glaciers froze directly to the ground when they formed since Mars is missing Earth's more dramatic glacial terrain. To find out whether the ice actually stayed put, Grau Galofre and her team created models of identical ice sheets, subjecting one to the conditions on Earth and another to the conditions on Mars.

The scientists discovered that it is Earth's gravity that causes meltwater to pool beneath a glacier instead of draining right away. The pooled water makes the glacier move faster, something like the hydroplaning that happens when cars end up sliding uncontrollably because of a layer of water between their tires and the road. However, on Mars, lower gravity means drainage occurs much faster, Grau Galofre and her colleagues found that not as much water accumulates below the ice, so Martian glaciers are not able to travel as fast or as far.

Some glaciers on Mars might have had an assist from below. The research team hypothesized that to push the glaciers any faster, there would have had to be enough stress to make up for weaker gravity. Creep deformation is a phenomenon that happens when both temperature and pressure from the weight of the heavy ice above, known as overburden pressure, put enough stress on ice for it to start deforming. On Earth, creep deformation is not nearly as prevalent as the sliding of ice which results from glacial melt that pools beneath that ice. Formations on Mars like parts of the Argyre basin in its southern hemisphere were possibly affected by this extra speed.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It turns out that glaciers which behave much like what the researchers propose happens on Mars also occur on Earth. In the extreme northern reaches of the Arctic, the ground lying beneath some glaciers shows hardly any of the abrasions and gouges that mark places where enough meltwater keeps the ice moving and scraping out new features in its wake.

It is possible, Grau Galofre thinks, that glaciers could have once been a haven for primordial Martian life, if it existed, since they would have doubled as a nearly endless source of water and as a shield from harsh radiation. Earth creatures such as black ice worms thrive inside glacier ice.

Maybe something long frozen is waiting to be discovered deep inside a glacier on Mars.

The research is described in a paper published in July in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.