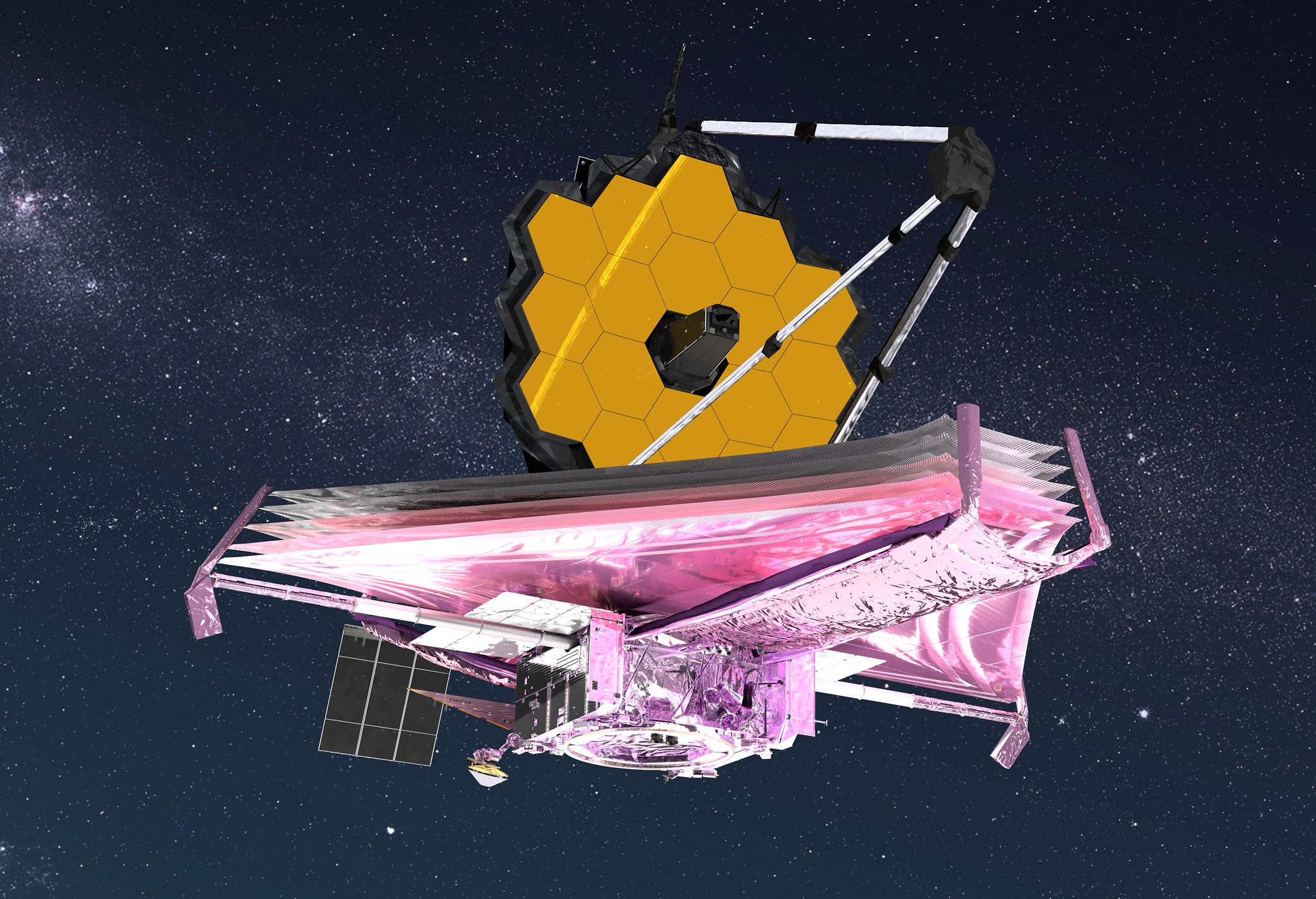

Here's how the James Webb Space Telescope is aligning its mirrors in deep space

Here's how it works.

The James Webb Space Telescope continues to fine-tune its mirrors to ultimately peer into the deep and distant universe.

The telescope launched Dec. 25 with the 18 hexagonal segments of its primary mirror and its secondary mirror folded up and stowed so that the components would survive the rigors of liftoff. Now, the telescope is close to reaching its way to its deep-space destination and is starting to move those mirror segments into alignment.

"Before launch, the mirrors were all positioned with the pegs held snug in the sockets, providing extra support," Marshall Perrin, deputy telescope scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute that manages Webb, said in a NASA blog post on Thursday (Jan. 13).

"Each mirror now needs to be deployed out by 12.5 millimeters [about half an inch] to get the pegs clear from the sockets. This will give the mirrors 'room to roam' and let them be readied in their starting positions for alignment," Perrin added.

Live updates: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope mission

Aligning the mirror segments is a multi-month process that will require several blurry and "ugly" testing images to ensure everything is going to plan, NASA engineers said during a livestreamed press conference Jan. 8. The mirrors should be aligned around April 24.

"I like to think of it as, it's like we have 18 mirrors that are, right now, little prima donnas, all doing their own thing, singing their own tune in whatever key they're in," Jane Rigby, Webb operations project scientist, said during the press conference. "We have to make them work like a chorus, and that is a methodical, laborious process."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Perrin added that the process will require "some patience," especially seeing as the mirrors can be manipulated to high precision. Further adjustments to the mirror segments are possible in increments as small as 10 nanometers, which is only one-ten thousandth the width of a human hair. The first adjustments, he added, won't be quite so fine, only about a centimeter.

Webb's mirror control system only moves one actuator at at time to reduce the complexity of the system electronics, and also to ensure safety (in that a single maneuver is easier to monitor than several.) These actuators are tiny motors that allow the team to move the individual mirror segments.

Another major factor that Webb has to contend with is heat, as the telescope needs to be ultra-cool to perform its observations in the infrared.

"To limit the amount of heat put into Webb’s very cold mirrors from the actuator motors, each actuator can only be operated for a short period at a time," Perrin said. "Thus, those big 12.5-millimeter moves for each segment are split up into many, many short moves that happen one actuator at a time."

Webb's mission operations center at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center sends scripts to the telescope, which run under human supervision. "At full speed, it takes about a day to move all the segments by just 1 millimeter. It's about the same speed at which grass grows," Perrin said.

As Webb continues its adjustments, the mirrors and the instruments will continue to cool from natural radiation into space post-launch. The telescope's next major space maneuver will be Jan. 23, when the mission team expects that it will execute an engine burn and glide towards its ultimate "parking spot" in space known as L2, or the second Earth-sun Lagrange point, a gravitationally stable point in space. Webb will orbit the sun from this spot during its lifetime.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.