James Webb Space Telescope will get best view yet of 'failed stars' and rogue planets

Not much is known about the tiny celestial bodies, which are hard to see.

We're just weeks away from the release of the first images taken by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, and while that occasion will be momentous, there is far more science to come.

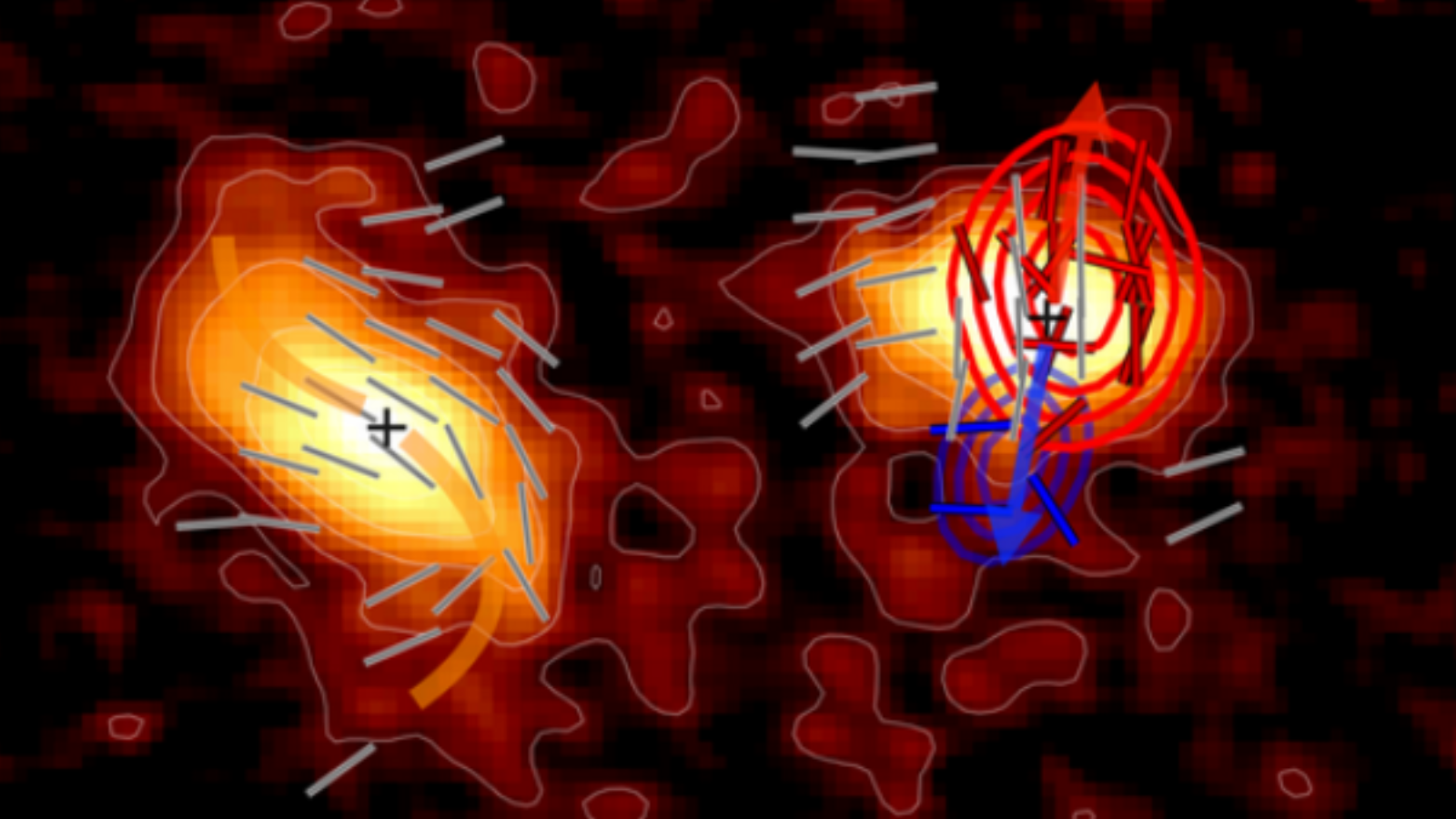

One of the James Webb Space Telescope's early programs is a study that plans to use Webb to observe the nearby stellar nursery NGC 1333. The international team of scientists will image the stellar nursery's small, faint residents — primarily brown dwarfs and rogue planets — which have been difficult to see with less-powerful telescopes.

Brown dwarfs are considered failed stars. Though they begin their lives in the same way as true stars, in clouds of collapsing gas and dust, they do not gather enough mass to begin fusion. Thus, they are quite small and do not produce bright light as other stars do, making them tough to see. Brown dwarfs exist somewhere between gas giant planets and red dwarfs, the smallest and coolest type of main sequence star.

Related: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope is almost ready for science. Here's what's next.

"The least-massive brown dwarfs identified so far are only five to 10 times heftier than the planet Jupiter," Alek Scholz, an astronomer at the University of St Andrews in Scotland and leader of the study, said in a statement. "We don't yet know whether even-lower-mass objects form in stellar nurseries. With Webb, we expect to identify cluster members as puny as Jupiter for the first time ever."

The team will also study rogue planets, or celestial bodies that formed in a stellar system before being ejected into space, left to float freely among the stars. (True planets and exoplanets are gravitationally bound to stars.)

To observe these small, dark objects, the researchers will use Webb's Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, allowing the scientists to do spectroscopy on dozens of objects at the same time.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"For an unambiguous confirmation of a brown dwarf or rogue planet, we need to see the absorption signatures of molecules — water and methane, primarily — in the spectra," Ray Jayawardhana, an astronomer at Cornell University and a member of the research team, said in the statement. "Spectroscopy is time-consuming, and being able to observe many objects simultaneously helps enormously. The alternative is to take images first, measure colors, select candidates, and then go and take spectra, which will take much more time and relies on more assumptions."

The study is part of Cycle 1 of the Guaranteed Time Observations program, which will occur during Webb's first year of operations.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.