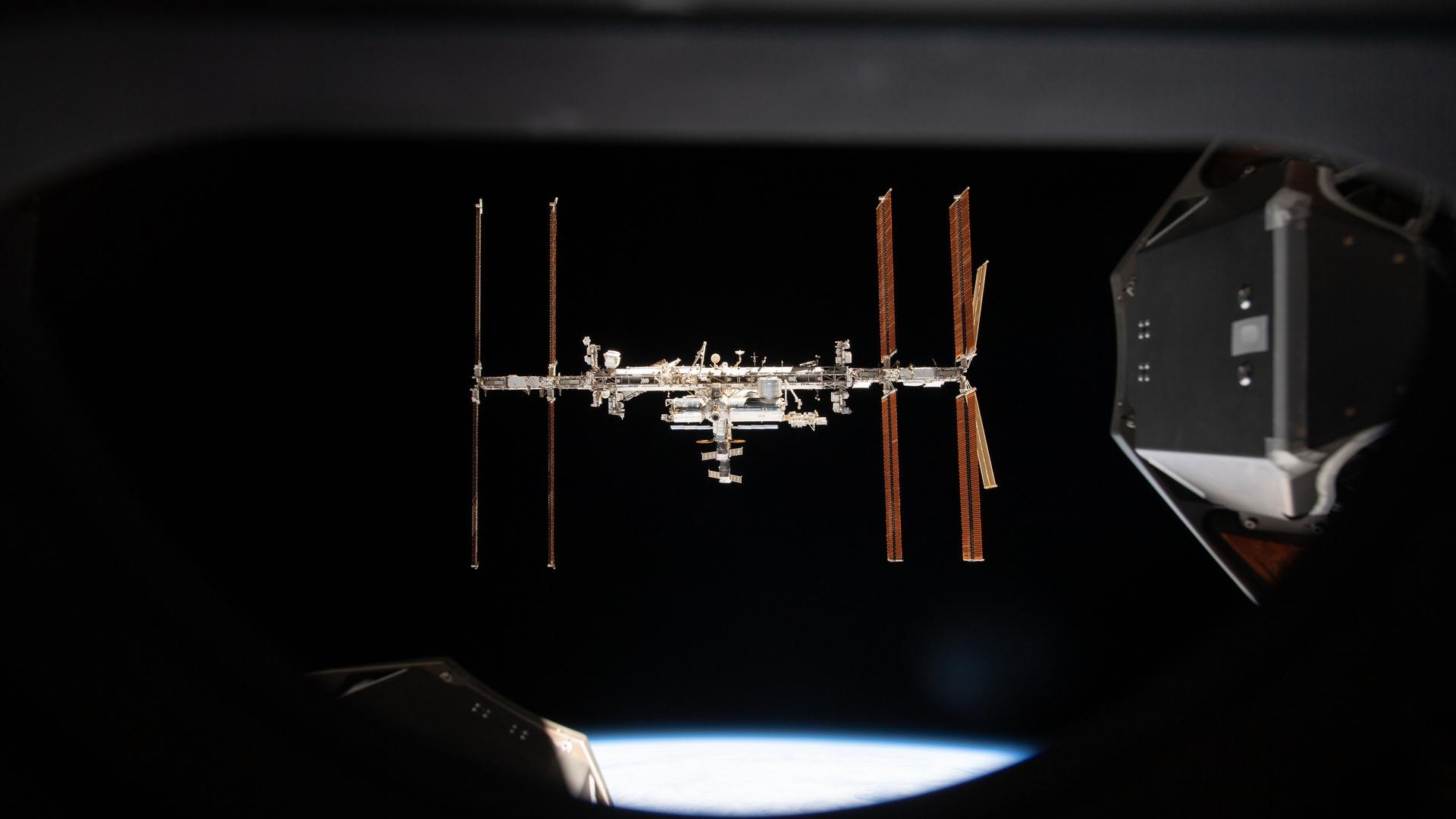

As the ISS turns 25, a look back at the space laboratory's legacy

The ISS just celebrated its 25th anniversary — soon, the station will be hanging up its boots.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Hurtling through space at 17,500 miles per hour, the International Space Station (ISS) circles the entire globe roughly once every 90 minutes — which amounts to 16 sunrises and sunsets every 24 hours. At any point in time, the station is home to no less than seven international crew members, with the station's living and working areas amounting to the size of an average six-bedroom house.

The ISS has undoubtedly become an iconic piece of human history, and on Nov. 20, NASA celebrated the station turning 25. This anniversary in particular feels a little bittersweet because the station itself is set to be decommissioned by 2030, as the structure will become too fatigued around then to be able to house astronauts safely. So, with an expiration date being placed on humanity's foothold in space, it's worth talking about what we've learned and why it matters.

Related: Quantum chemistry experiment on ISS creates exotic 5th state of matter

In an obvious way, the ISS has been pivotal in the development of space hardware. For engineers, the station has provided the unprecedented challenge of creating a habitat in low Earth orbit that can safely host a semi-permanent population of people. Microgravity conditions, the threat of space debris collisions and harmful cosmic radiation also create a novel environment in which scientists had to solve logistical problems.

And because of those solutions, the ISS has provided an opportunity for humans to test new technologies that could one day be used during longer, farther crewed ventures to other areas in the solar system and perhaps even deep space. But while the ISS has clearly been a source of technological innovation, maybe more importantly, it has allowed us to understand how being in space affects people.

The human body evolved on the surface of the Earth, so it's built to stay on Earth. Space presents a new set of challenges. For example, astronauts on the ISS have to spend two hours a day exercising to stave off muscular atrophy, as their bodies do not have to continually work against gravity on the surface of the planet thereby deteriorating their strength.

"From the ISS programme, NASA has learned really what happens to the human body in zero-G over long duration flights. When we go to Mars we'll be committing those people to a long duration mission, so it's imperative to know what that's going to do to their bodies," Brian Berry, commercial crew programme mission manager at NASA, said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Living on the ISS also presents a number of psychological challenges for astronauts. Isolation, a lack of privacy, and a high expectation working environment can all contribute to quite difficult working conditions. Studying the psychological effects of living and working in space on the ISS has helped researchers understand what people will need to thrive on longer voyages into deep space.

At the eventual conclusion of the ISS programme, the station will be "deorbited" in a controlled manner, where the entire station's facilities will break up and vaporize as the units enter Earth's atmosphere. Any possible remnants of the station that reach the Earth's surface will land in a remote part of the ocean.

Over the course of its lifetime, thousands of engineers, computer scientists, researchers and astronauts from all corners of the world have all contributed to the functioning and flourishing of the ISS. This station, in a sense, therefore transcends scientific achievement. It serves as an important symbol of what can be achieved when countries put aside their differences and work towards a common goal.

Conor Feehly is a New Zealand-based science writer. He has earned a master's in science communication from the University of Otago, Dunedin. His writing has appeared in Cosmos Magazine, Discover Magazine and ScienceAlert. His writing largely covers topics relating to neuroscience and psychology, although he also enjoys writing about a number of scientific subjects ranging from astrophysics to archaeology.