Chemically, Earth Is Basically a Less Volatile Version of the Sun

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

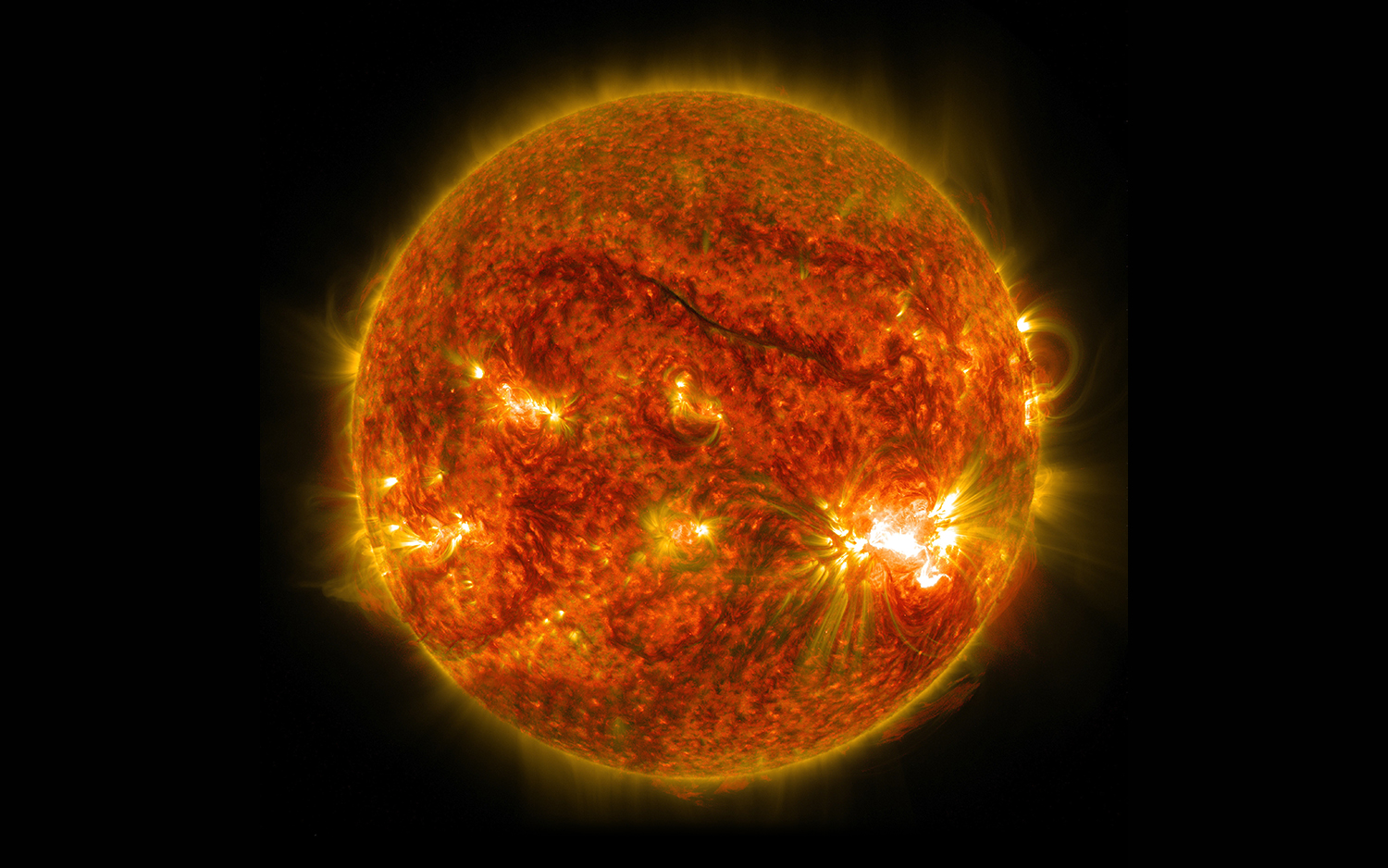

Our sun is a lifeless, fiery ball of gas fueled by a nuclear inferno. Earth, meanwhile, is a rocky, layered planet covered by water and teeming with life. Nevertheless, the elemental composition of these two celestial bodies is surprisingly similar.

The elements in the sun and Earth are pretty much the same, though Earth had less of the sun's more volatile elements, which evaporate at high temperatures, a new analysis reveals.

This suggests that Earth formed from material in the solar nebula — the cloud of dust and gas that shaped the sun — but volatile elements such as helium, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen were stripped away during our planet's formation. The tools used in the current study could also help reveal the composition of exoplanets orbiting distant stars, the study authors reported. [Spaced Out! 101 Astronomy Images That Will Blow Your Mind]

First, the researchers analyzed elements that appeared in rocky meteorites that fell to Earth, known as chondrites. Chondrites, which also formed in the protosolar nebula, are often used as proxies for understanding the sun's chemical makeup, the researchers wrote.

They also evaluated the sun's elemental composition from observations of radiation in the sun's photosphere — the outer "shell" that emanates light — and incorporated data from solar turbulence and theoretical models.

Though the most abundant elements in the sun are hydrogen and helium, the researchers discovered a total of 60 elements was abundant in both meteorites and photosphere; these elements were probably also plentiful in the protosolar nebula before the sun's birth, according to the study.

Then, the scientists compared their results to the elemental composition of Earth's core and primitive mantle, which can be gleaned through a combination of mathematical models, seismic data and rock samples. They found that while Earth shared most of the same elements as chondrites and the sun, Earth had "devolatilized" — lost volatile elements over time — and that this was "an inherent process" as the inner solar system took shape, the researchers wrote.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This comparison yields a wealth of information about the way the Earth formed," study co-author Trevor Ireland, a professor of geochemistry and cosmochemistry with the Research School of Earth Sciences at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, said in a statement.

Similar evaluations could be done for planets orbiting stars other than our sun.

"Rocky exoplanets are almost certainly devolatilized pieces of the stellar nebulae out of which they and their host stars formed," the researchers wrote in the study.

Pinpointing the elemental makeup of faraway exoplanets will play an important part in determining if they can support human life, lead study author Haiyang Wang, a doctoral candidate with ANU's Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, said in the statement.

"The composition of a rocky planet is one of the most important missing pieces in our efforts to find out whether a planet is habitable or not," Wang said.

The findings appeared online March 14 in the preprint journal arXiv, and will be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Icarus.

- Shine On: Photos of Dazzling Mineral Specimens

- What Will Happen to Earth When the Sun Dies?

- Top 10 Questions About Earth

Originally published on Live Science.