Earth science missions are still challenged 50 years after 1st Earth Day

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Human space exploration has shown us that we live on a beautiful swirl of green and blue and white — even when life on Earth is riddled with sorrows, sickness and challenges knotted beyond measure.

Today (April 22) marks the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, an annual celebration inspired by spaceflight and an apt moment to look back on a planet that humans can — albeit occasionally, briefly and in very small numbers — leave, and to consider how we are treating it.

The milestone comes amid a sweeping pandemic that has already killed tens of thousands of people, sprawling wildfire seasons, evaporating biodiversity, weather patterns that have unraveled to the point of becoming utterly unrecognizable and profoundly different versions of the human experience for those with riches than those without.

Related: Earth science is more important than ever (op-ed)

It's a lot to handle, and dealing with the host of global challenges we face will likely require help from the fleet of sensors that orbit Earth, looking down on our planet and giving us a broader yet more detailed perspective than we can glean on the ground.

That's nothing new for NASA, of course. "NASA's got a long history of monitoring Earth from space," Annmarie Eldering, an environmental scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, told Space.com, pointing to early weather satellites and the transition over the decades to more advanced research missions.

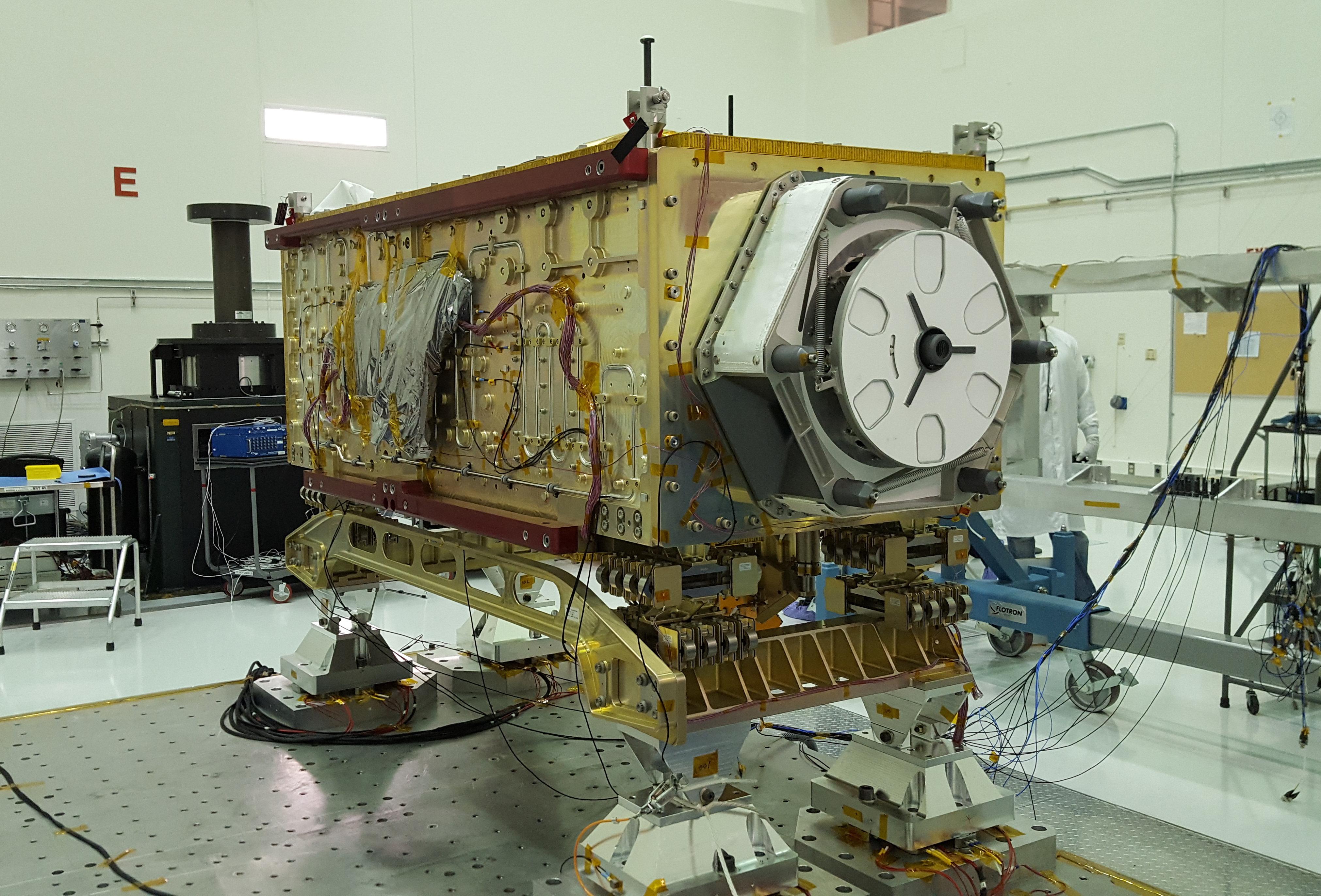

Currently, NASA runs a total of 28 space-based Earth-observing missions. Eldering works with two such missions right now: Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 and -3 (OCO-2 and OCO-3), which measure atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. The projects were dreamed up in the 1990s, she said, but the necessary observations are so finicky that scientists only felt confident designing a mission in the 2000s.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Back and forth budgets

But OCO-3 hit a snag on its road to launch when, in March 2017, its funding went missing in the newly inaugurated President Donald Trump's budget request. Congress reinstated the money and Eldering said the politics didn't particularly interfere with the mission's development — and is unremarkable, if inconvenient, for Earth-observing missions.

"That just feels like business as usual: money comes and money goes. Almost every project I've been on goes through some period of uncertainty or limbo, it's just been the nature of the way our work gets funded," Eldering said. "You talk to anybody who's been in this business for the last 50 years, if you have a brilliant idea, it's guaranteed it will take you many, many years to go from great idea to something actually happening."

OCO-3 happened; it flew to the International Space Station last year and began work in August. It's making observations smoothly and the team expects to release the instrument's first batch of science data later this month. Eldering said she's particularly pleased because, although the new mission was designed as a successor, OCO-2 is still going strong so scientists can use data from the two missions in tandem.

As OCO-3 proves, a budget request can't singlehandedly end a mission. The president's budget request is just a request, and Congress determines NASA's final budget. But that sort of limbo still a less-than-ideal way of doing business if your core priority is Earth, Rachel Licker, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit science advocacy group, told Space.com.

"It creates hiccups and it creates delays in important research and insights that people need to be safer and to be making better-informed decisions," Licker said. "So it affects scientists, but it also affects society in terms of the information we have at our disposal."

Two missions yet to launch have endured the budget will-they-won't-they more than OCO-3. Each year in office thus far, Trump's budget requests have canceled two specific Earth-observing missions. (Congress has not yet finished the current budget negotiations, so while these missions were eliminated for 2021, their funding remains uncertain.)

The Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem mission, or PACE, is one of those projects. For Licker, it's a good example of the way that new missions can provide data that matters in people's lives, even if they never know the project responsible. That's because PACE can catch big growths of tiny aquatic plants that can have dangerous side effects. Harmful algae blooms can close beaches and reduce air quality, and PACE would help scientists better understand how these blooms impact public health.

(NASA declined interview requests for PACE project scientist Paula Bontempi, who is also an acting deputy director in NASA's Earth Science Division, and Sandra Cauffman, acting director of the division. In a town hall about the budget request held on March 20, Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science, elided over potential mission cancelations, including the two Earth-observing missions. "We recognize that discussion is ongoing," he said. Read his thoughts on Earth Day here.)

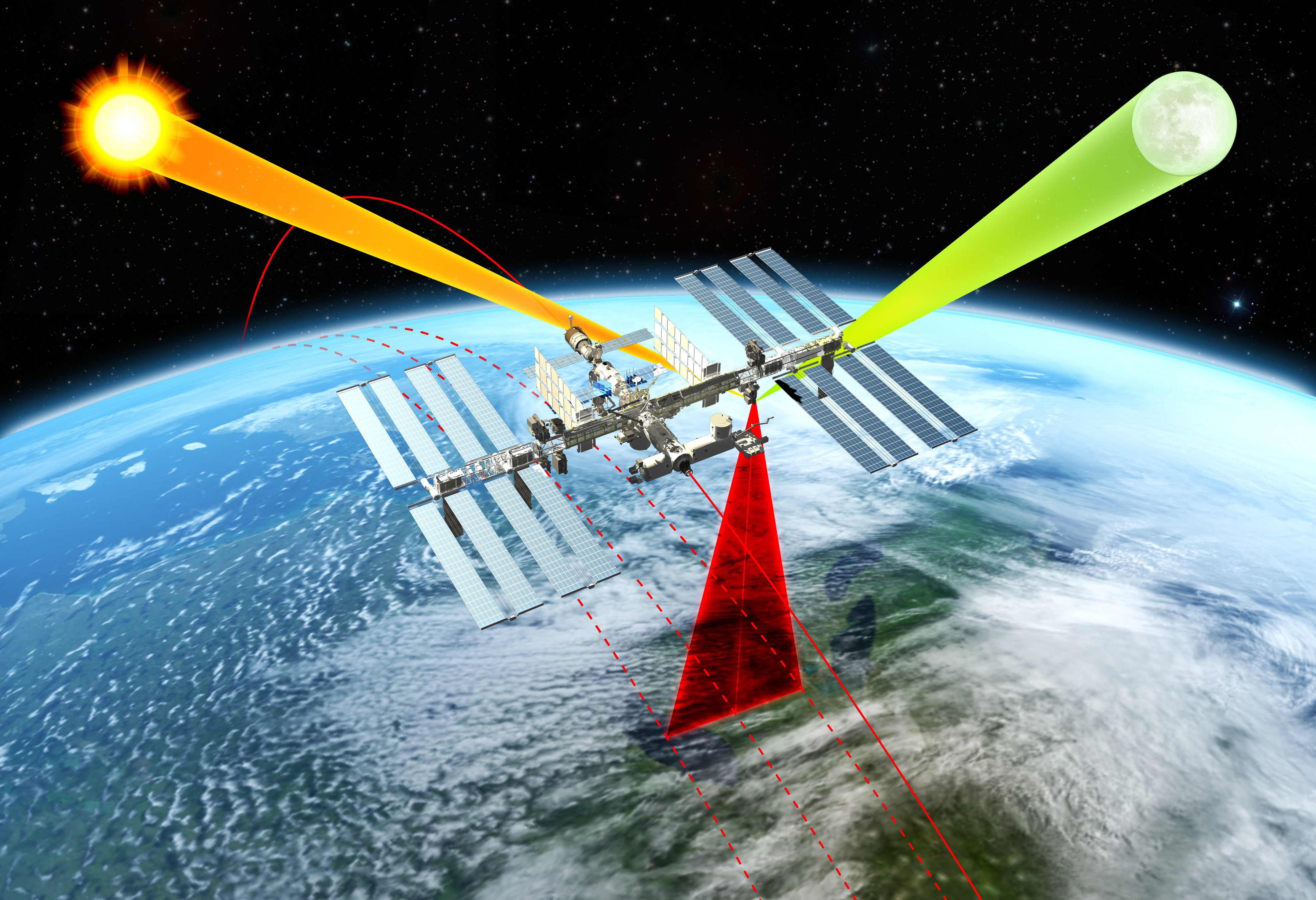

The other Earth science mission that has been repeatedly canceled in requests and revived by Congress is the Climate Absolute Radiance and Refractivity Observatory (CLARREO) Pathfinder. Like OCO-3, CLARREO Pathfinder is destined for the International Space Station. There, it would calculate how much sunlight Earth reflects in specific wavelengths of visible and near-infrared light. It would also provide data for scientists to confirm that other Earth-observing instruments are gathering accurate measurements.

Those tasks mean CLARREO Pathfinder would represent a step forward for scientists studying a wide range of climate-relevant phenomena, including clouds and land use patterns, Yolanda Shea, a project scientist for the mission and an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Langley Research Center in Virginia, told Space.com. "Those are the types of measurements we need to monitor Earth's climate at the level that will give us more certainty about any decisions we may need to make in the future," she said.

CLARREO Pathfinder, which is facing a late 2022 launch to the space station, will last only a year, which perhaps complicates understanding its role in climate science as a whole. "It's a one-year mission, we're not observing decadal-scale changes," Shea said, "but the data that will be taken can all be used to conduct science."

Assuming, of course, the budget comes through, and so far it has despite the proclaimed cuts. "In our day-to-day, we try to move forward with our work: as long as there's funding appropriated for the mission we'll work on the mission," Shea said. "There have always been tugs of war over funding and priorities, and I think NASA has a great history of doing a lot with whatever we're given. We think about the work that we can do and impact we can have and we figure out how to use those resources to support the public."

Beyond any one agency

The CLARREO Pathfinder mission would be far from alone in focusing on light reflecting off our planet, Earth scientist and former NASA astronaut Kathy Sullivan told Space.com. Whether a satellite is billed as measuring wind speed or ocean color or anything else, it is actually measuring reflected or emitted light.

Then, scientists need to use their skills to convert such data to the parameter of interest, and to convey that information to people making decisions that affect lives and livelihoods. That translation relies on the entire institution of science, she said.

"I care about that whole span of knowledge creation, not just about the next gadget that goes into orbit," Sullivan said. "People are so unaware of how much they rely on insight and information about the planet to go about their daily lives. We just presume it will be there, but it won't be there without continuing to monitor, without continuing to measure, and without continuing to advance the fundamental underlying knowledge."

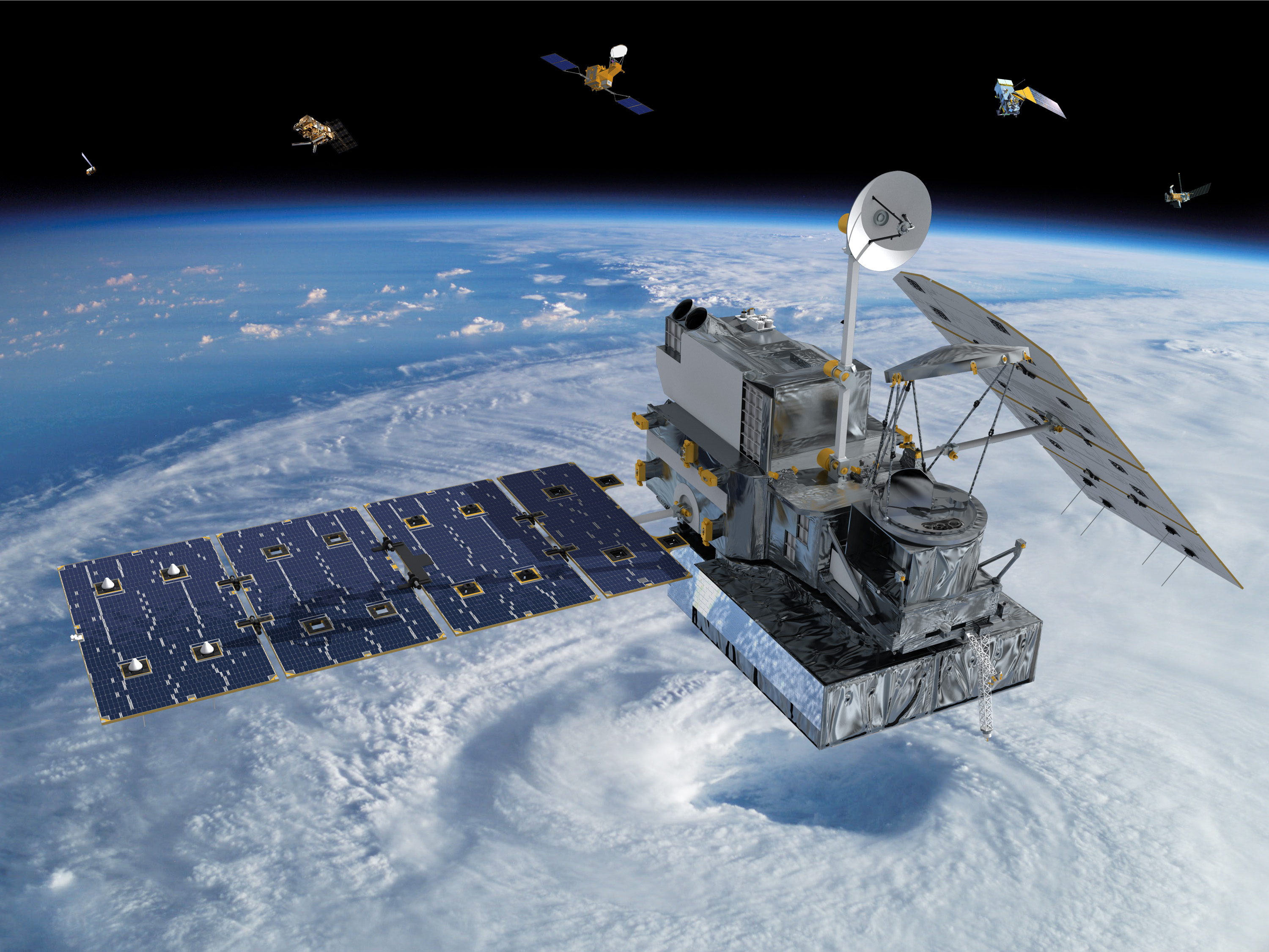

That burden doesn't just rest on NASA, of course, although NASA is a leader and its partnerships, like those with the European Space Agency (ESA), are vital scientific endeavors.

"A strong NASA is good for a strong ESA and a strong Earth-observation program worldwide," Josef Aschbacher, head of ESA's Earth Observation Programs, told Space.com. He said he hopes PACE and CLARREO Pathfinder fly, especially because he believes they align nicely with ESA programs.

But he isn't worried about their fates yet. "This is the beginning of a debate and the real budget decisions will be made later on," he said. He also said he takes confidence from how closely NASA's programs have matched the priorities of the so-called decadal survey meant to guide Earth science through 2027 based on input from the scientific community. (PACE and CLARREO Pathfinder both ranked highly in that report.)

Pandemic planet

In Aschbacher's portfolio, ESA is currently overseeing 15 operational Earth-observation missions, with 34 more in development. Perhaps the pride of its fleet is the Copernicus program's series of Sentinel satellites, each tailored to a different type of measurement. The next installment in the series, due to launch later this year, is a partnership with NASA that will measure sea levels, one of the most vital types of data about climate change impacts.

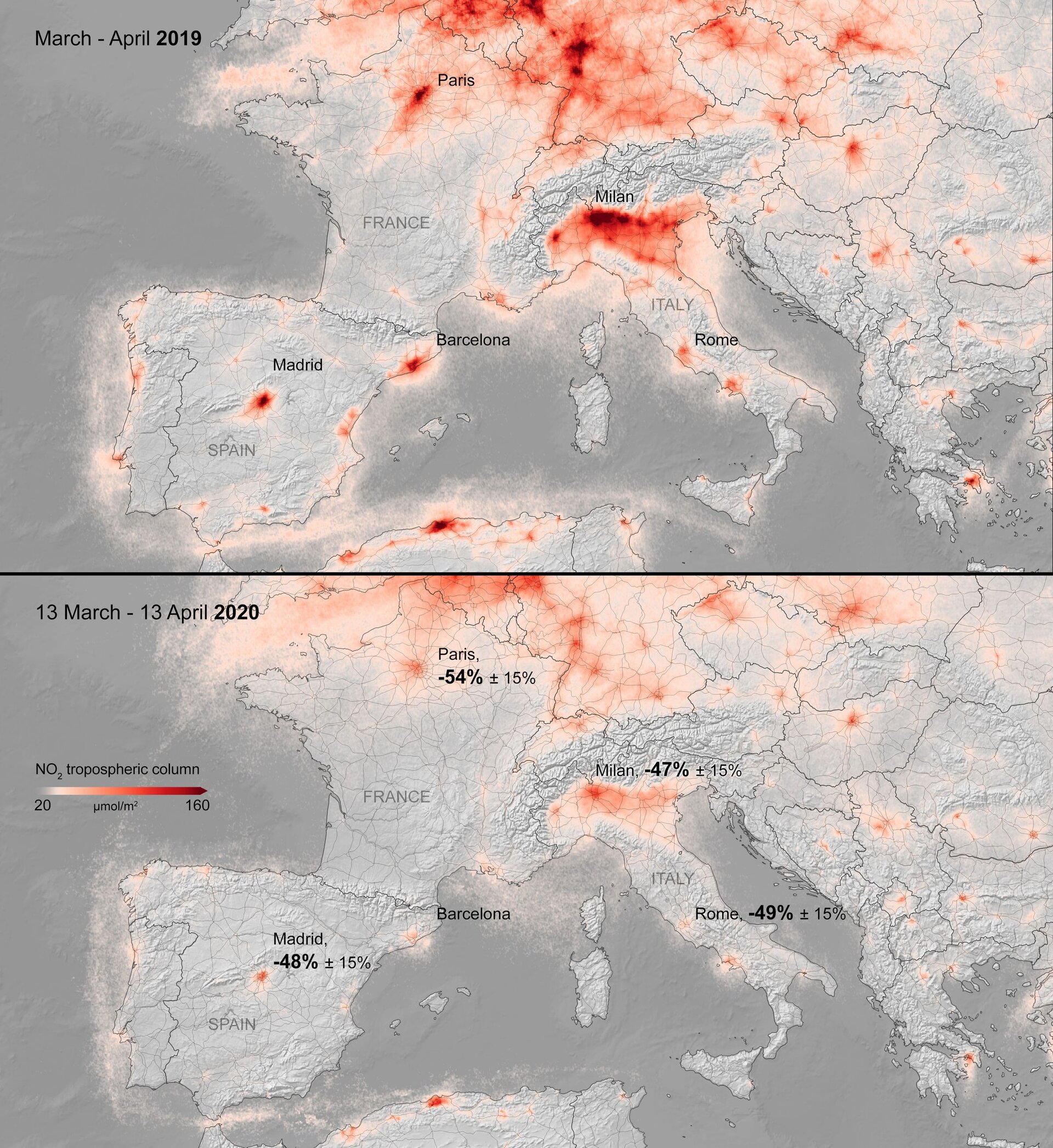

Others in the series study the atmosphere. Sentinel-5P, for example, has found the spotlight recently for its measurements of falling nitrogen dioxide levels over cities shut down as a public health measure to slow the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

About that pandemic: even as counties scramble to reassess their budget in the wake of the economic upheaval and emergency costs that the pandemic has provoked, Earth science missions shouldn't be cut, Aschbacher emphasized, noting that satellites like Sentinel-5P will help experts track countries rebounding from the pandemic.

And environmental science will still be vital, no matter how the public health situation changes. "Especially after COVID, we cannot forget that we have to make investments in line with creating a sustainable planet," he said. "There may be a danger that pollution may be increasing because pollution thresholds may be a bit more relaxed, but I think the opposite should take place."

Other Earth-observing satellites will be vital in helping scientists understand how the disease could interact with other disasters. "Floods ain't gonna stop because there's a global pandemic," Beth Tellman, a geographer at Columbia University's International Research Institute for Climate and Society who focuses on using satellite data to understand flooding, told Space.com, adding that scientists predict the Midwestern U.S. will see bad floods this year.

That said, she, like the other scientists I spoke with for this story, isn't pessimistic about Earth's future. "What coronavirus has shown me is we can do a lot when we have the will to," Tellman said. "Transformation is possible. It gives me hope in a really weird way: what is the opportunity for response to climate change and disasters in the future? We clearly have more power in collaboration than we think."

Her colleague, Andrew Kruczkiewicz, who focuses on the remote sensing of disasters, hopes that the jarring alignment of celebration and pandemic sparks new conversations about the inequities involved in observing Earth from space. "Only some people have the privilege to observe the Earth," he said. "We have a responsibility, I believe, to communicate the constraints and the opportunities to the people that we're observing and potentially helping, but also interacting with in ways that may not be fully understood."

The pandemic has also perhaps laid bare the ways in which even the best satellite data cannot foist good outcomes on humans.

"The arc of the last 50 years we've seen this growing capability and understanding of our earth system and new techniques and technologies to learn about it and gather data, that's a big plus," OCO-3's Eldering said from her background in climate science. "Have we advanced in our ability to make good policy decisions around that? It's kicks and starts."

- Earth Day 2019: These amazing NASA images show Earth from above

- Earth pictures: Iconic images of Earth from space

- Coronavirus pandemic's global impact seen from space in chilling satellite images

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.