Telescopes watch the sun bake a comet to death

The observations might explain why there are so few comets around the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A comet visiting the sun has disintegrated in front of astronomers' eyes in a series of unprecedented observations that may help explain why comets orbiting close to the sun seem to disappear.

The comet, called 323P/SOHO, was discovered in 1999 by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), a NASA/European Space Agency probe that constantly observes the sun. 323P/SOHO is one of the rare near-sun comets, which follow elliptical orbits that take them closer to the sun than the orbit of the solar system's innermost planet, Mercury. Theoretical models predict that many such comets exist, but only a few have been observed to date. The recent observation might explain why.

In the winter of 2020/2021, when 323P/SOHO last approached its perihelion, the closest point to the sun in its 4.2-year orbit, it had a high-profile audience. Some of the world's most powerful telescopes — including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Gemini North, Canada-France and Subaru Telescopes in Hawai'i and the Lowell Discovery Telescope in Arizona — watched as the comet made its close pass by Earth's star. Although the telescopes didn't see the moment of closest approach, the changes they observed during the few short months suggested that something unusual was going on with 323P/SOHO.

Related: Giant comet was active way farther from the sun than expected, scientists confirm

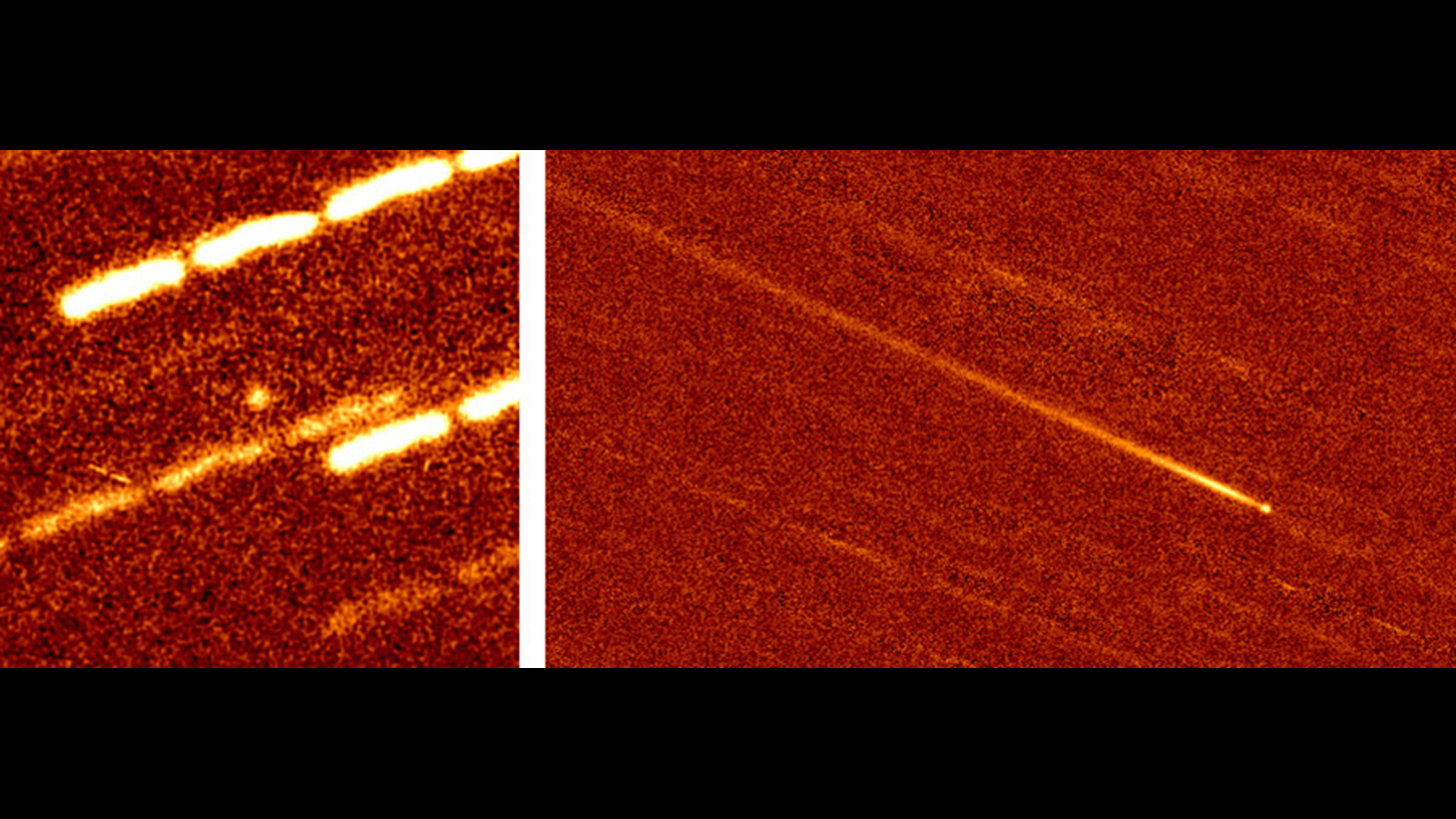

The Subaru Telescope, which searched for the comet as it approached perihelion in December 2020, saw only a simple small dot. However, when the comet reemerged into view of Hubble, Lowell, Canada-France and the Gemini-North telescopes in February and March 2021, it looked very different, sporting a long tail of ejected dust.

Scientists believe that the visible change happened as the comet disintegrated because of the extreme heat near the sun.

"The intense radiation from the sun caused parts of the comet to break off due to thermal fracturing, similar to how ice cubes crack when you pour a hot drink over them," the research team said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The comet also changed color, which became "unlike anything else in the solar system." The observations also found that 323P/SOHO was spinning rapidly, completing one rotation in just half an hour.

"Observations of other near-sun objects are needed to see if they also share these traits," Man-To Hui, who was a University of Hawai'i researcher at the time of the observations and is now an assistant professor at Macau University of Science and Technology, said in the statement.

Observing near-sun comets, however, is no easy feat. Most of them are discovered accidentally by sun-observing satellites, such as SOHO.

The study was published in the Astronomical Journal on Tuesday (June 14).

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.