Snoopy to the Moon! Apollo 10 Commander Looks Back on Historic Flight 50 Years Ago

Fifty years ago, astronauts flew just 9 miles above the moon's surface in preparation for Apollo 11's lunar landing.

Fifty years ago today, NASA's Apollo 10 mission rocketed to the moon. The crew got just 9 miles from the surface, but they never landed.

Often referred to as a dress rehearsal for the lunar landing, this mission was an integral step forward in the Apollo program, because it included all of the steps of a crewed lunar landing — minus the lunar landing. Space.com sat down with mission commander Thomas P. Stafford to look back at the crucial mission that made the lunar landing possible. The remarkable mission was not only an impressive feat on its own, but it also pointed out the remaining dangers with crewed missions to the moon. These efforts not only supported the Apollo 11 lunar landing, but also the following Apollo missions and even modern day efforts to return to the moon.

Apollo 10 launched from Cape Kennedy, Florida, on May 18, 1969, and landed back on Earth on May 26, 1969. Stafford, command and service module pilot John W. Young and lunar module pilot Eugene A. Cernan made the trip. Stafford is the only surviving member of the crew.

Related: Apollo 10: NASA's Lunar Landing Dress Rehearsal in Photos

The procedures tested during Apollo 10 showed NASA that a lunar landing really was possible and what issues might arise during its successor's touchdown.

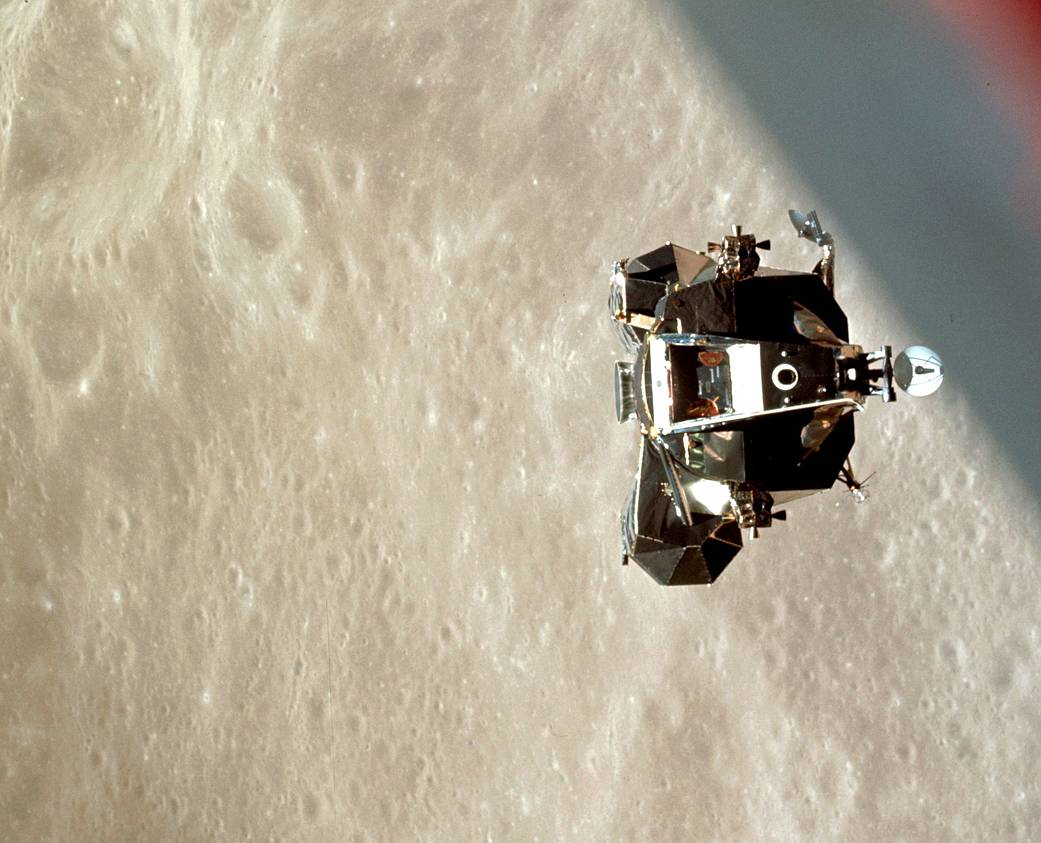

During the flight, Cernan and Stafford undocked the lunar module, which was called Snoopy, and achieved translunar injection burn. The astronauts completed a lunar orbit and descended to just 47,400 feet (about 9 miles, or 14.4 kilometers) above the moon's surface before ascending to rendezvous and dock with the command and service module during lunar orbit.

The astronauts completed this close encounter with the lunar surface above the Sea of Tranquility, right where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would land the lunar module just a couple of months later. During this dry run, the crew collected data that helped NASA's teams on the ground to refine network tracking techniques, lunar flight control systems and lunar module trajectories.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Of course, the Apollo 10 crew also got to see Earth from space, an experience that has stayed with Stafford over the 50 years since he landed. "It was absolutely awesome," he told Space.com. "When you're at the moon, you look back at the Earth and it's about the size of an orange." It was the sort of view that couldn't be predicted, despite hundreds and hundreds of hours in simulators, he added.

But Stafford also remembers how close he came to touching down on the lunar surface, explaining that computer systems weren't ready in time for a landing during the Apollo 10 mission. "The software was not completely finished or reliable enough for 10," he said. "They barely got us there for 11."

In addition to providing updates for the Apollo 10 software to support Apollo 11, data from this mission also helped NASA to determine how much fuel would be necessary to complete a lunar landing. Still, as Stafford recalled, it was a pretty close call — Armstrong and Aldrin rapidly ran out of fuel on their way down to the moon's surface.

"Charlie Duke was the [Apollo 11] CAPCOM [capsule communicator], and he was calling out, 1 minute to go of fuel. And then 45 seconds, 30 seconds, and I remember when he called 20 seconds and then Neil landed with 17 seconds of fuel," Stafford said. "I would've had zero seconds," he joked.

Before becoming an astronaut, Gen. Stafford served in the Air Force and was a test pilot. This prepared him to not only work with Project Apollo but also to fly in two Project Gemini missions — Gemini 6A and Gemini 9. While Apollo 10 is often overshadowed by the lunar landing, the mission was much more than just a dress rehearsal for Apollo 11. The data collected on Apollo 10 informed the entire future of spaceflight from there on out.

Apollo 10 was also the first time that astronauts on the command service module filmed in color so that back on Earth, people could watch in vivid color as the lunar module and the command service module docked after the lunar module's lunar descent. The remarkable, colorful television broadcast of the mission even earned the Apollo 10 crew an Emmy award.

For Stafford, Apollo 10 is a reminder of what it takes to do groundbreaking work. Having flown in the Gemini program, Stafford was a veteran of the space program before he ever even flew as the commander of Apollo 10. That makes him an expert on what it actually takes to do the impossible and push the boundaries of human spaceflight. Stafford himself said it best when said that, to do incredible things, "you gotta think out of the box!"

- Future Moon Exploration: How Humans Will Visit Luna (Infographic)

- How the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Worked (Infographic)

- The Apollo Moon Landings: How They Worked (Infographic)

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.