New Views of Pluto Reveal Weird Bright Spot

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This story was updated at 1:59 p.m.ET

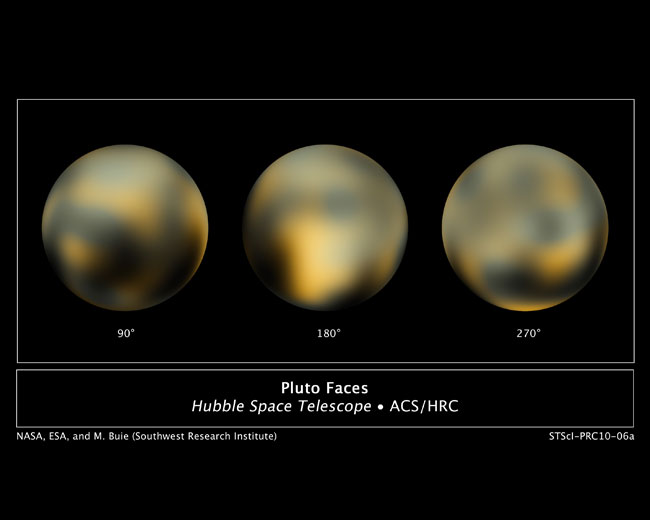

The Hubble Space Telescope has returned the most detailedimages of Pluto ever taken.

The new photos reveal the strange mini-world in neartrue-life color, close to what the dwarf planet would look like to an observertraveling toward it in a spacecraft, scientists said. The surface appearsreddish, yellowish, grayish in places, with a mysterious bright spot that isparticularly puzzling to scientists.

Some of the colors revealed in the new pictures of Plutoare thought to result from ultraviolet radiation from the sun interacting withmethane in the tenuous atmosphere of the dwarf planet. The bright spot apparentnear the equator has been found in other observations to be unusually rich incarbon monoxide frost.

"This is our best candidate, that it's carbonrelated," Marc Buie of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colo.said during a Thursday teleconference.

The newimages should provide "a real treasure trove of information inunderstanding the nature of Pluto and how it evolved and changes withtime," Buie said.

Pluto is a world on the fringe of the solar system withthree small moons called Charon, Nix and Hydra. It was discovered in 1930 byastronomer Clyde Tombaugh, and was long considered a full-fledged planet. Butin 2006, after much debate in the astronomical community, Pluto was downgradedto "dwarfplanet" status, along with other cosmic bodies such asCeres and Eris.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientist Mike Brown, professor of planetary astronomy atCaltech in Pasadena, Calif., who as discoverer of Eris was partly responsiblefor this demotion, says not to feel too bad for Pluto.

"Pluto is a fascinating world and it doesn't reallycare what we call it," Brown said. "I think this is an exciting thingto see and an exciting thing to try to understand how the entire solar systemworks."

Pluto is the destination for NASA's NewHorizons probe, a spacecraft currently on a course to fly by Pluto and itsmoons in 2015.

"It's about halfway there already and when its getsthere we're going to get all sorts of great pictures and great data," Buiesaid. "But these [Hubble] maps have been used already to help plan theencounter.

When compared to older data from 1994, the new photos ?taken by Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys ? reveal a surprising amount ofchange in the appearance of Pluto. Over that period, Pluto has gotten redder,while its northern polar region has gotten brighter and its southern hemispherehas gotten darker.

One reason for the variability, scientists say, is Pluto'shighly eccentric ? or oblong ? orbit, which causes strong variations intemperature. Pluto takes 248 years to make a full orbit around the sun.

"Right now it's close to being springtime onPluto," Brown said. "In the fall things will freeze out. It's just aridiculously extreme place to be."

Since the dwarf planet is so small and so far away, it hasbeen difficult to gather detailed data before. When New Horizons arrives, thatprobe should reveal even higher quality data. But until then, Hubble's visionis by far the best view we've ever gotten.

"This has taken four years and 20 computers operatingcontinuously and simultaneously to accomplish," says Buie, who developed aspecial computer program to sharpen the Hubble data.

The findings are detailed in the March 2010 issue of theAstronomical Journal.

- As Science Evolves, So Does Pluto

- Pluto's Identity Crisis Hits Classrooms and Bookstores

- Gallery: Our New Solar System

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.