New Space Telescope to Map Infrared Sky Better Than Ever

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

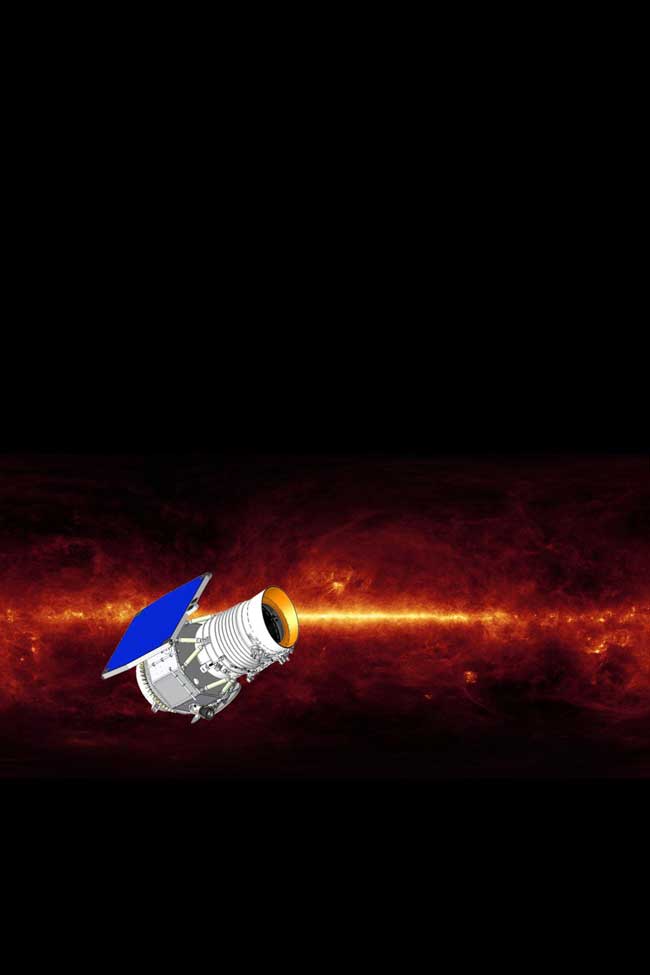

A new NASA spacecraft is ready to tackle a grueling nine-month photo shoot of cosmic proportions to seek out more than just the stars.

Instead of observing just one particular object, NASA?s new Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) will scan the entire sky 1 1/2 times during its mission to spot the coolest stars, dark asteroids and blazing galaxies that shine bright in the infrared. The spacecraft is set to launch Friday from California?s Vandenberg Air Force Base in California and head for an orbit circling the Earth?s poles.?

The $320 million infrared-vision spacecraft is designed to observe the sky at levels hundreds of times more sensitive than infrared sky surveys of the past.

WISE may not represent the most sensitive infrared instrument when compared to NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope or the European Herschel Space Observatory. But its all-sky view casts the widest possible net to gather a wealth of scientific observations ? not to mention find future telescope targets for Spitzer and Herschel. Its wide gaze may also uncover exotic, rare objects in the universe that most telescopes would never find in the sea of stars.

"The wide-angle approach used by WISE is essential when looking for rare or unique objects, such as the most luminous galaxies in the Universe or the closest stars to the sun," said Ned Wright, WISE principal investigator at the University of California in Los Angeles.

Unlike the naked human eye, WISE can see infrared light at longer wavelengths that may reveal cold, dusty or distant objects which might otherwise not show up in an optical survey.

A wide cosmic net

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Doing a fast and efficient survey of the sky requires special stargazing skills. The Spitzer Space Telescope and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope can detect fainter objects than WISE, because of larger mirrors that focus on one patch of sky to collect incoming light for long periods of time. But each of the pointed telescopes cannot cover more than 1 percent or so of the sky.

WISE uses a scan mirror that slowly tracks the same patch of sky for 8.8 seconds, even as the spacecraft orbits the Earth. The mirror then quickly snaps back to its starting position in 2.2 seconds, so that WISE can take still shots of the infrared sky every 11 seconds.

"WISE will look at everything, but will not detect everything," Wright told SPACE.com.

The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) and Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) conducted similar all-sky surveys in the 1980s, but with less sensitive detectors ? IRAS used just 62 pixels to cover four infrared bands, and COBE had just one pixel per band.

By contrast, WISE has so-called "megapixel eyes" that can cover a million pixels, so that it can spot more of the sky per picture. It also covers four of the same infrared bands surveyed by IRAS and COBA, with one megapixel per band.

"WISE will have hundreds of times the sensitivity of IRAS, and hundreds of thousands of times better sensitivity than COBE, in the overlapping bands," said Peter Eisenhardt, WISE project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif.

Discovering the infrared universe

The infrared eyes of WISE should reveal hundreds of near-Earth objects (NEOs), such as asteroids and comets, during the mission's sweep of the sky.

"We're not optimized for a NEO search, but we're pretty good at it," said William Irace, WISE project manager at JPL. "The way to look at WISE is that it's a nice proof of concept mission for a comprehensive NEO survey."

Farther out, WISE may find very cool brown dwarfs at temperatures of -94 degrees F (200 K). Such failed stars appear within the WISE detection range as far out as the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, about four light years distant from Earth.

"We may find the brown dwarfs which are the centers of the nearest extrasolar planetary systems, the first place beyond the solar system that humanity may visit," Eisenhardt said.

A more unlikely find could involve the Oort cloud, or the large spherical cluster of comets which sits almost a light year out from our sun. If WISE happens to spot a large gas planet the size of Neptune or Jupiter far off in the Oort cloud, such a discovery could once again throw the definition of a planet into disarray.

WISE can also detect ultraluminous infrared galaxies that radiate with the light of up to a trillion suns, Eisenhardt explained. Those galaxies may show up as far as 10 billion light-years away, or back in the time when the universe was three to four times younger and galaxy formation had kicked into high gear.

Similarly, Wright wants to see how the distribution of galaxies stacks up against the cosmic microwave background, which represents leftover radiation from the time of the Big Bang.

Above and beyond

The WISE mission's survey will eventually end when an onboard supply of solid hydrogen, called cryogen, runs out after about 10 months. The cryogen helps WISE prevent its own infrared signature from interfering with its detectors, by keeping the infrared telescope and instruments at -429 degrees F (17 degrees K).

But the WISE team hopes for a possible three-month extension even after the cryogen is exhausted, because the shorter infrared bands may still uncover useful data. Perhaps NASA might consider the extension as a reward for a job well done ? especially given that both NASA and its subcontractors have kept the WISE mission on schedule during the run-up to launch, according to Irace.

Past all-sky surveys have also provided a smorgasbord of data for scientists to examine long after the original mission ended. For instance, hundreds of papers still refer to the IRAS survey that took place more than a decade ago.

"This is why we like to say that the legacy of all-sky surveys endures for decades," Eisenhardt said.

- Video - A New Closest Star? - Getting WISE to Brown Dwarfs

- Images - Spitzer Telescope Sees Universe in Infrared

- A List of the Major Space Telescopes

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.