Fly Higher, Fly Lighter: 'Ballute' Technology Aimed at Moon Missions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

BOULDER, Colo. -- Moviegoers may recall it as that nifty bit of high-speed technology used in 2010: The Year We Make Contact -- the space age equivalent of playing air bag bumper car with Jupiter.

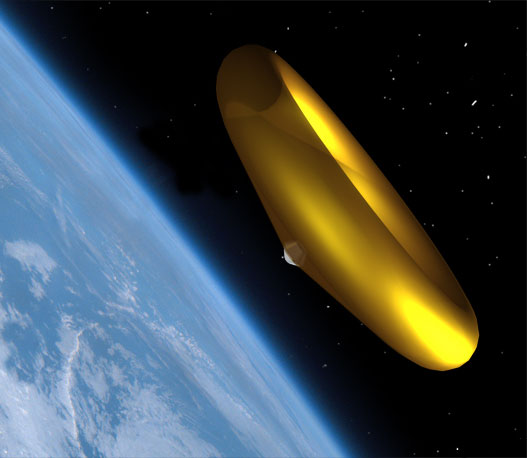

A "ballute" was used to slow the spacecraft once it reached the giant planet, a device that allows for aerocapture around a celestial body that's enveloped in an atmosphere.

Now fast forward two decades since that sci-fi movie's release in 1984.

NASA's Exploration Systems Mission Directorate is on the lookout for new concepts for its Vision for Space Exploration -- the White House-backed Moon, Mars and beyond agenda. And on November 16th, NASA selected a concept from Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corporation for inflatable thin-film ballutes for return from the Moon.

Not only Moon-to-Earth traffic could benefit by using the ballute/aerocapture technique. So too could missions to Mars, as well as future probes to Titan, the largest moon of Saturn, and other distant destinations.

Fly higher, fly lighter

Aerocapture uses atmospheric drag to slow down an incoming satellite so that it enters an orbit around a planetary body more efficiently. Taking this approach translates to using less propellant to slip a satellite into a proper orbit, lower launch costs, and makes more room on spacecraft for sensors and other payload gear.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By using a ballute -- a fusion word from balloon and parachute -- a spacecraft can slow down enough to go into orbit around the target planet.

"We call this concept 'fly higher, fly lighter', said Kevin Miller, Senior Technical Manager of Spacecraft Systems in the Civil Space Systems division of Ball Aerospace here.

The idea is to use a large ballute that flies high in the atmosphere and decelerates itself and the attached payload over a period of time. That high-flying maneuver would reduce heating loads on the ballute.

"The temperature on the ballute does get hot, but it's within the limits of thin film materials," said Jim Masciarelli, Principal Engineer for Spacecraft Systems at the company. You pick a point in the atmosphere, but not so deep that the ballute sees high heating rates, he said.

Given a ballute-enabled aerocapture, a payload could be released to drop into a pre-selected landing zone, touching down on Earth via parachute or parafoil. Using this technique to put an incoming payload into an orbit for retrieval is feasible too.

Ballute bonuses

The ballute's lightweight "fabric" comes from the high-temperature, flexible polymeric film family that includes kapton, Miller told SPACE.com. No need for the type of thermal protection system like that in use on the space shuttle or akin to an incoming Apollo lunar mission of the past.

Masciarelli noted that thin film materials technology has advanced over the years, as has the manufacturing of large inflatable structures, high-temperature adhesives, and analytical design tools. "Obstacles in the past...now the obstacles are not quite so big," he explained.

There are several ballute bonuses: For one, you don't have to confine everything inside a fixed space of an aeroshell or heatshield. Furthermore, it doesn't really matter what payload is being toted. The ballute technology is viewed as modular and scaleable, Masciarelli pointed out.

Walk before you fly

Ball Aerospace is working on the ballute concept along with other team members, including NASA's Langley Research Center, Georgia Tech, and ILC Dover. The newly won contract has a total value of $14.12 million.

Now scripted is a four-year, step-by-step test program.

Materials and different assembly methods are to be studied. What shape is the right shape, and what ballute size ranges are required will be assessed.

Test ballutes of roughly 10 feet (3 meters) in diameter will be fabricated, evaluated in vibration facilities, a large wind tunnel, and vacuum chamber. Similarly, small scale models are to be tested in hypersonic wind tunnels.

Eventually, in-space demonstration of large inflatable ballutes seems to be mandatory, Miller said, to show the idea is ready for prime time. In adopting new technology to space projects there is always "institutional hesitation", he said.

"You've got to walk before you fly," Masciarelli said.

High performance return from the Moon

The ballute concept can apply to a small science package, large cargo, made-on-the Moon propellants, or human-carrying spacecraft such as NASA's Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) -- all hardware that would be on a heading from the Moon to Earth, Masciarelli said.

In addition, the ballute concept could operate all the way from a terra firma launch pad to Earth orbit, Masciarelli continued, permitting an astronaut to climb inside the inflatable device and escape from the space station or a damaged space shuttle.

That idea is not new. In the 1960's, General Electric was exploring a similar notion under a program that was later shelved: Man Out Of Space, Easiest - or MOOSE.

"First things are Moon and Mars," Miller said, with the ballute idea permitting a very high performance return from the Moon, but also serves as enabling technology for getting people to Mars. "The 'and beyond' is coming," he said.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.