How a Solar Flare Amped Up Chaos of Hurricane Irma

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

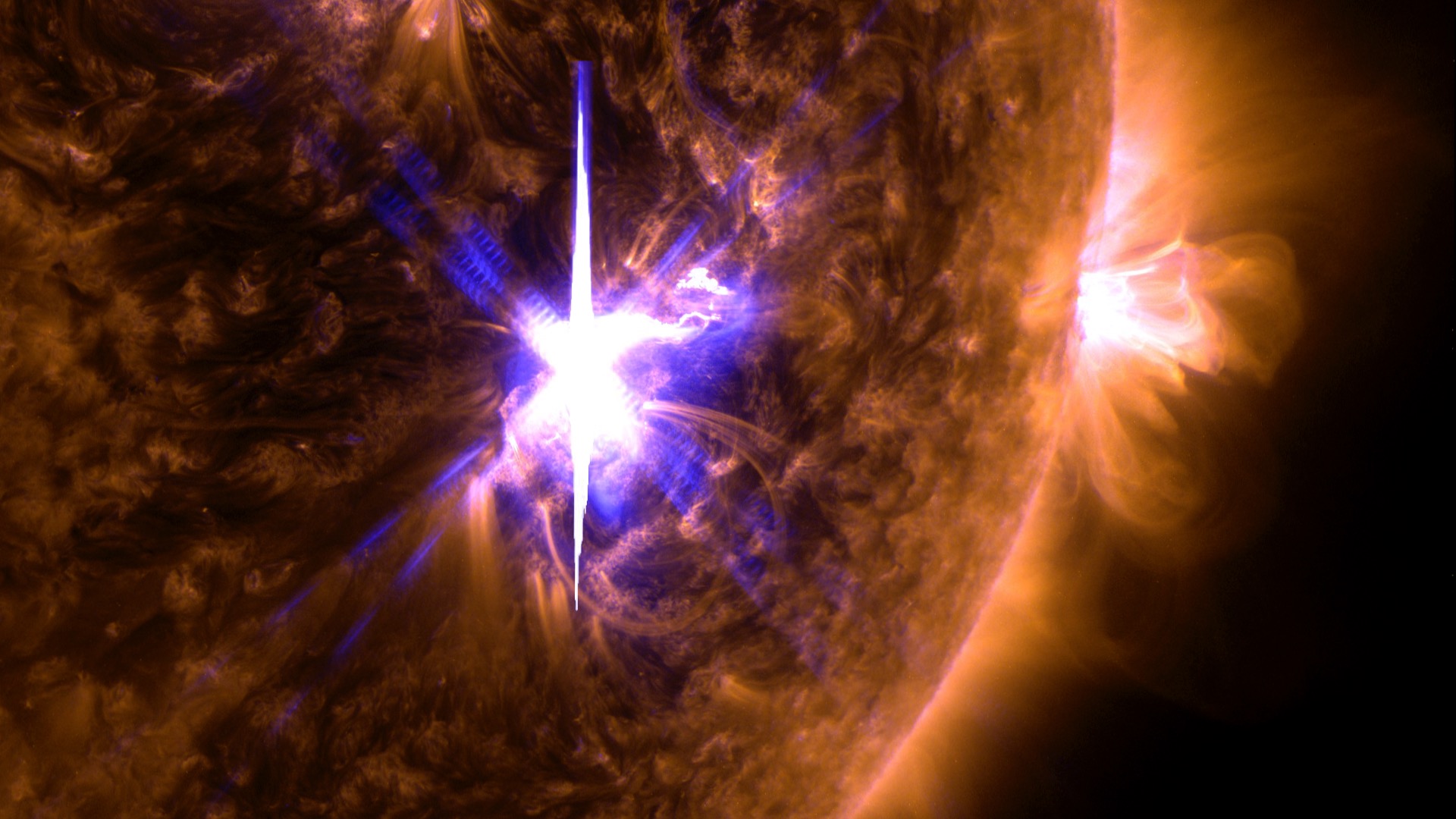

During Hurricane Irma's advance over the Caribbean in September 2017, the sun coincidentally produced its own space weather. This interfered with communication during the response to the severe terrestrial weather.

That's according to new research looking at how a 10-day period of high solar activity affected radio communication during the hurricane. The situation came to a head on Sept. 6, as Irma was approaching the Virgin Islands and the sun produced a gigantic X9.3 solar flare pointed toward Earth. This flare knocked out radio communication.

"Space weather and Earth weather aligned to heighten an already tense situation in the Caribbean," lead author Rob Redmon, a space scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said in a statement from the American Geophysical Union, which published the new research. [In Photos: The Monster Solar Flare of September 2017]

Space weather includes a range of phenomena, from the harmless and beautiful northern lights to coronal mass ejections that fling tons of highly charged plasma out of the sun. More-dramatic types of space weather can affect satellites orbiting Earth, including communication and navigation systems, and can block radio waves moving through Earth's atmosphere.

That can mean trouble for emergency response, which often relies on radio communication. And Hurricane Watch Net, a group of amateur radio enthusiasts who assist NOAA during hurricanes, had reported problems during the 10-day period of solar activity in September.

"You can hear a solar flare on the air as it's taking place. It's like hearing bacon fry in a pan. It just all of a sudden gets real staticky, and then it's like someone just turns the light completely off — you don't hear anything. And that's what happened this last year on two occasions," ham radio operator and Hurricane Watch Net Manager Bobby Graves said in the statement. "We had to wait 'til the power of those solar flares weakened so that our signals could actually bounce back off the atmosphere. It was a helpless situation."

The researchers behind the new paper didn't try to figure out the extent to which the communications problems might have slowed down or interfered with the hurricane response. Instead, the scientists focused on precisely what was happening in the sun's atmosphere and how that behavior affected Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To do so, the researchers tapped into a range of satellites in orbit right now, including missions studying the sun, like NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), and those focused on terrestrial weather, like NOAA's Geostationary Satellite Server (GOES) network. The researchers said they hope that by piecing together a detailed picture of what happened and when, they will be able to better understand how space weather works.

That goal should get a lift from NASA's new Parker Solar Probe, currently scheduled to launch on Aug. 11. It's meant, in part, to help scientists better predict space weather and the impacts of the sun here on Earth. That won't prevent another coincidence of severe space and terrestrial weather, but it could help responders better handle such a situation.

The new research was described in a paper published July 25 in the journal Space Weather.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.