More Comet Samples Needed to Understand Solar System's History, Scientists Say

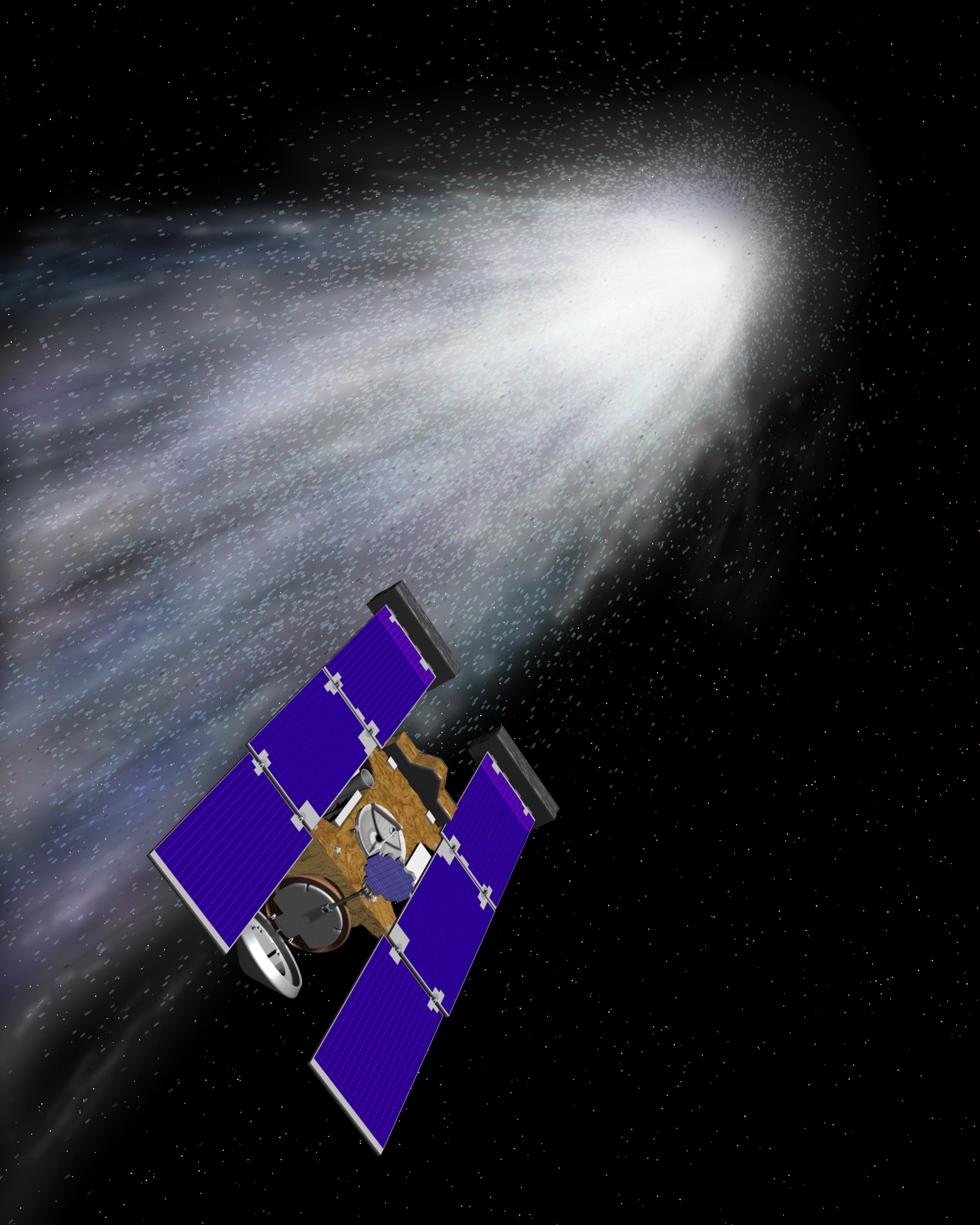

More samples of comets are urgently needed to better understand the early history of the solar system, say researchers analyzing comet dust brought back to Earth by NASA’s Stardust mission in 2006.

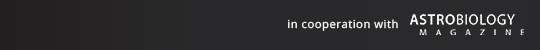

Those dust particles are from Comet 81P/Wild (also known as Wild 2) and date to the beginning of the solar system, containing clues about its earliest history.

"The future of Stardust science," a paper published last year in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, summarizes the roughly 150 scientific publications based on Stardust mission science. It makes an important point about the limits of our knowledge of the early protosolar disk of gas and dust from which the solar system formed — that Wild 2 and other Kuiper Belt comets (those originating from the ring of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune) are poorly represented in our samples of extraterrestrial material. [NASA's Stardust Mission Brings Cosmic Dust to Earth (Photos)]

In contrast, asteroids are represented in our collections by meteorites and have been well documented for over a century, while moon material has been collected and brought to scientists for analysis by the Apollo astronauts.

Andrew Westphal, a senior member of the Stardust team and an astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley, urged investigators to seek out more Kuiper Belt material to study on Earth because of its unique origins.

"As you sample farther and farther out in the solar system, you sample material that is more and more primitive," said Westphal, the lead author of the paper. "Particularly when you get a sample from a comet, you get a sample [that has been] in deep freeze for 4.6 billion years."

Approximately 10 percent of a typical Kuiper Belt comet is unaltered interstellar material. Some of this material consists of pre-solar grains — circumstellar dust grains condensed in the outflows (emissions) of other stars long before our solar system formed. Most of the interstellar material, however, probably formed in the interstellar medium.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Little information on water

Determining whether liquid water was ever present within Wild 2 is also an important goal of comet investigators. Astronomical evidence shows that cometary water may have variable deuterium-to-hydrogen (D-to-H) ratios, and that the average ratio differs from that of water on Earth.

A famous example of this is Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, which was studied up close by the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission from 2014 to 2016. Other cometary D-to-H ratios have been measured by ground-based telescopes.

If comets have different D-to-H ratios in their water than Earth's water does, this likely means that comets did not deliver the majority of water to Earth's surface. Instead, investigators speculate it was asteroids that brought the water, but more study is needed of both asteroids and comets to help confirm the hypothesis.

Unfortunately for Stardust investigators, no "volatiles" — molecules with low boiling points, such as water — survived slamming into the spacecraft's aerogel and aluminum foil collector at 6.1 kilometers per second (3.8 miles per second, or 13,680 miles per hour). That situation has made it challenging to advance the science on cometary D-to-H ratios.

"The rocks survived, but no water was preserved," Westphal said. "Some rare organics, however, did preserve their D/H ratios."

The investigators also looked for phyllosilicates, which are clays that preserve water inside of them, but studies of particles collected by Stardust have not yielded any phyllosilicates to date.

There may be another opportunity to study the material from a comet. The proposed Comet Astrobiology Exploration SAmple Return (CAESAR) probe — one of two "New Frontiers" mission finalists NASA is considering for launch in the mid-2020s — is designed to snag samples from Comet 67P and return them to Earth.

Westphal's research on stardust is supported by NASA's Emerging Worlds program and the Laboratory Analysis and Return Samples (LARS) program.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. This version of the story published on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.