Escape from Mars! Red-Planet Dust Storms Linked to Atmosphere Loss

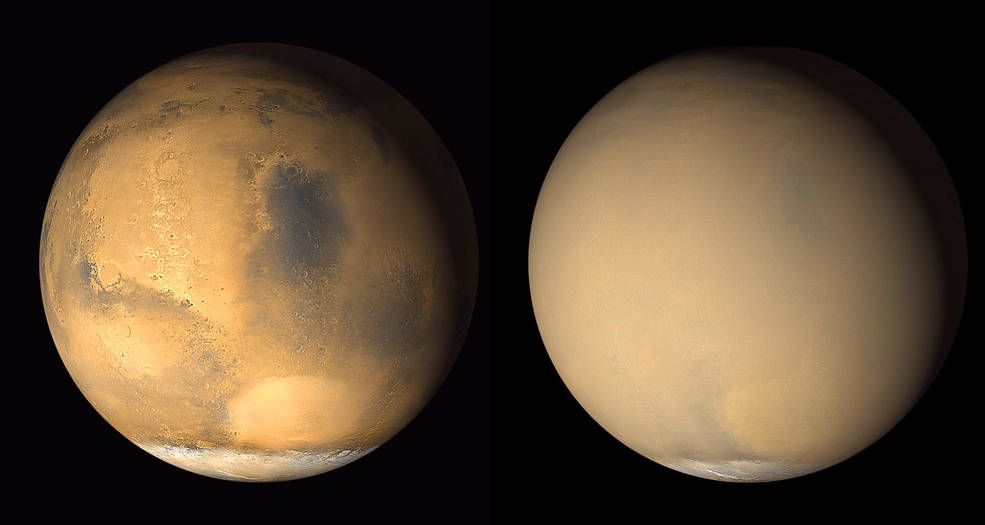

Dust storms that take over the Martian globe play a key role in promoting gas escape from the Red Planet's atmosphere, according to a new study.

Scientists know that water flowed on the surface of Mars in the ancient past; there's lots of evidence of this, from riverbeds and canyons to minerals soaked with water (such as hematite).

Why Mars dried up, however, is still under investigation. The leading theory suggests that most of the Martian atmosphere was stripped by the solar wind shortly after the planet lost its global magnetic field, about 4 billion years ago. The Martian air became so wispy that the planet couldn't support running water on its surface anymore. [Photos: Ancient Mars Lake Could Have Supported Life]

In the new study, researchers reanalyzed dust-storm observations made by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). MRO saw water vapor increase in the middle atmosphere, about 30 to 60 miles (50 to 100 kilometers) up, during regional dust storms. It was during a global dust storm in 2007, however, that water vapor was really affected. The vapor moved to a higher altitude and increased in volume more than a hundredfold, the data showed.

"We found there's an increase in water vapor in the middle atmosphere in connection with dust storms," study lead author Nicholas Heavens, a geophysicist at Hampton University in Virginia, said in a statement. "Water vapor is carried up with the same air mass rising with the dust."

Other observations, by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter, suggest there's a link between Mars' middle-atmosphere water volume and the escape of atmospheric hydrogen into space — at least during years without global dust storms.

It's unclear what the relationship is during years with planetwide dust storms; they don't come along too often.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It would be great to have a global dust storm we could observe with all the assets now at Mars, and that could happen this year," study co-author David Kass, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the same statement.

Regional Martian dust storms tend to occur during the planet's northern spring and summer, NASA officials said.

"In most Martian years, which are nearly twice as long as Earth years, all the regional storms dissipate, and none swells into a global dust storm," NASA officials wrote in the same statement. "But such expansion happened in 1977, 1982, 1994, 2001 and 2007. The next Martian dust storm season is expected to begin this summer and last into early 2019."

Not everybody is keen on a pall of dust to settle over Mars. NASA's long-running Opportunity rover needs solar power to keep rolling along; it shuts down operations during dust storms. And the agency's InSight lander is scheduled to launch toward Mars in May and land there in November; if a dust storm happened before touchdown day, mission planners would likely need to adjust parameters for a safe entry, descent and landing, NASA officials said. And even Martian orbiters would be affected because they wouldn't be able to see as well.

Whenever a dust storm happens, however, the robotic explorers at Mars will take advantage of the opportunity to learn more about its effects on the Red Planet's atmosphere.

"Before MAVEN reached Mars, many scientists expected to see loss of hydrogen from the top of the atmosphere occurring at a rather steady rate, with variation tied to changes in the solar wind's flow of charged particles from the sun," NASA officials wrote in the statement, referring to the agency's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution orbiter, which arrived at the Red Planet in September 2014. "Data from MAVEN and Mars Express haven't fit that pattern, instead showing a pattern that appears more related to Martian seasons than to solar activity."

The new study was published online Monday (Jan. 22) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com .

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.