End of the World As We Know It: What's the Draw of Dystopian Sci-Fi?

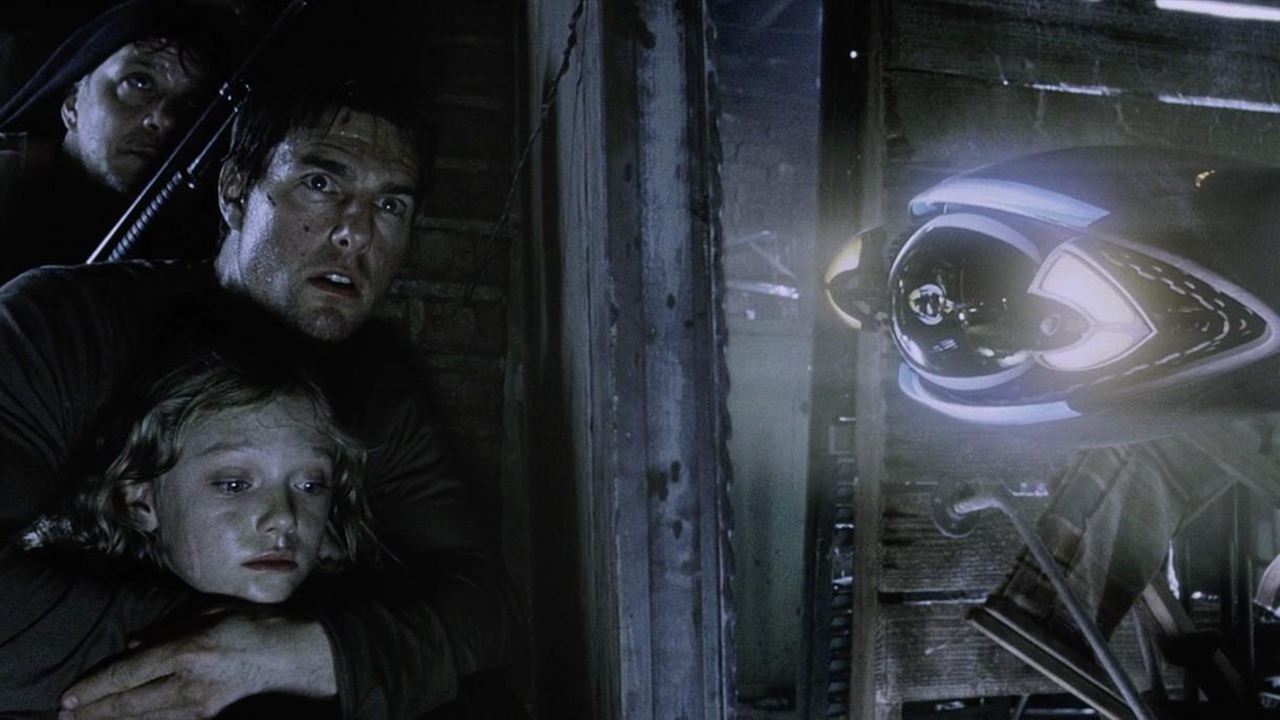

NEW YORK — Grim sci-fi and speculative fiction tales are often rooted in scenarios of oppression, moral disintegration or even total social collapse — from the perpetual surveillance and menace of "Big Brother" in George Orwell's "1984," to the deadly state-sanctioned battles fought by desperate children in Suzanne Collins' "The Hunger Games" trilogy.

But as bleak as these stories are, they have captivated readers and writers alike for decades. What drives authors to imagine these broken futures, and what might explain their enduring popularity?

On Oct. 6, a panel of writers at New York Comic Con (NYCC) explored their own relationships with dystopian sci-fi, and what characters who navigate dire situations in futuristic but degraded environments under totalitarian control can tell us about our world today — and about ourselves. [Doom and Gloom: Top 10 Post-Apocalyptic Worlds]

Some authors of dystopian sci-fi write to exorcise their own fears about how the future might go horribly wrong, panelist Lauren Oliver explained. But many also find that the genre allows them to address contemporary issues that might otherwise be too uncomfortable to confront, Oliver said. In her book "Ringer" (HarperCollins, 2017), Oliver uses a plot about cloning to highlight the topic of inequality, and to point out how some people in society are considered expendable — a grave problem that we face today, she told the audience at NYCC.

Dystopian science fiction can also introduce weighty topics, such as climate change, in ways that are entertaining, and not "dry or preachy," panelist Paolo Bacigalupi said.

When a reader meets a character who's trying to survive on a coastline that's been reshaped by rising sea levels, or who's coping with a Category 6 hurricane, the story resonates because it reflects circumstances that are already in motion around us, Bacigalupi said. Recent destructive hurricanes like Harvey, Irma and Maria have already raised concerns about the possibility of stronger storms to come, fueled by a warming world, he told the audience.

"Fiction lets you talk about something that hasn't happened yet, but we're leaning toward it," he said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Visiting a pessimistic future can also be surprisingly cathartic, because the reader knows that, however frightening that world may be, they can instantly leave it behind with the turn of a page, according to panelist D. Nolan Clark. A reader can experience the gamut of anxiety and unease, but there's also a sense of relief and safety when they step away from the book — which isn't always possible in real life, Clark said.

Dystopian fiction also provides a space where readers can wrestle safely with disturbing situations in an uncertain or malevolent world, panelist Scott Reintgen explained. And seeing characters make tough decisions and bravely face gut-wrenching challenges provides a shred of hope that goodness can still prevail, even when the odds seem hopeless, Clark said.

"A lot of us feel like we don't have any control over our lives these days. When you read about someone who stands up, you find in that character some kind of heroic model," Clark told the audience.

"The act of standing up and talking back to power in the most sassy voice you can think of — that in itself is heroic," he said.

Seeing that individual actions matter, and that even someone who seems powerless at the start of a story can be brave, and, in doing so, can dramatically change things for themselves and for others, is especially important for young readers, Oliver told the panel audience.

"Kids don't have fairies under the bed — they have monsters," she said. "You have to give them ways to imagine worlds in which they can be brave and make good choices. That's good work for a book to do."

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.