Planet of Promise: Small, Rocky World Could Harbor Life

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

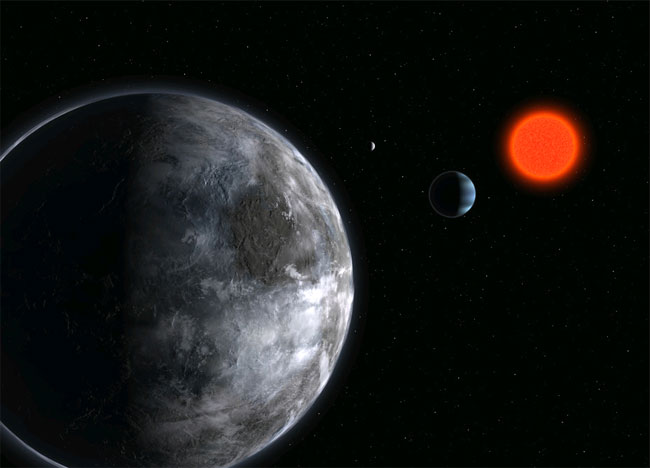

For thefirst time, astronomers have discovered a planet far, far away that might besimilar to Earth. This distant world, which pirouettes around a dim bulb of astar with the unglamorous name Gliese 581, may possibly sport a landscape thatwould be vaguely familiar to us - a panorama of liquid oceans and driftingcontinents. If so, there's the chance that it's a home to life - perhaps evenadvanced life.

It's been adozen years since the first planet around a star other than the Sun wasuncovered. Since then, small teams of astronomers have been flushing out freshplanetary prey at the rate of about one every two weeks. Today, it's easy tohave a blase attitude about this continuing drizzle of new worlds. With morethan two hundred planets already on the scoreboard, adding yet another soundsredundant.

But thisplanet is different.

It'sdifferent mostly because it's small. Nearly all the earlierdiscoveries were of massive worlds, lumbering giants comparable to Jupiteror Saturn. Such behemoths are likely to be buried in thick and toxicatmospheres, and seem ill-suited for supporting life. Mind you, it's not thatnature prefers the creation of such brawny planets; it's only that the wobbletechnique used to find them strongly favors the heavyweights.

However, bymeasuring the motions of bantam stars, such as the red dwarf Gliese 581, it'spossible to uncover lighter-weight worlds, since detectability depends on theratio of stellar to planetary mass. Gliese581c, as the new find is called, is the smallest yet discovered around anormal star, a mere 50% larger across than Earth. This diminutive size suggests(but does not prove) that it's a rocky world, like Venus, Earth or Mars.

In anotherstroke of luck, it turns out that this planet is likely to be - like Baby Bear'sporridge - at just the right temperature. Unlike Earth, it hugs Gliese 581 witha tight grip. It's five times closer to its runty star than Mercury is to ourSun. On the other hand, Gliese 581 is only a few percent as luminous as theSun. These two factors roughly cancel, and a simple calculation suggests anaverage temperature similar to the temperate zones of Earth.

Mind you, aplanet this close to its stellar master will most likely be tidally locked,with one side always facing its sun, and the other side perpetually turnedtoward the cold darkness of space. But computer models have suggested that ifsuch a world has an atmosphere, strong winds will distribute the heat of thesunny hemisphere around the planet. There should be a belt of moderatetemperatures somewhere near the twilight ring between light and dark. This ideahas received a bit of confirmation from recent infrared measures of anothernewly discovered planet, a tidally locked world named HD189733b. This gas giant seems to show a moderating of the temperaturedifference between its light and dark sides due to high-speed winds.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The bottomline is exciting. Out of the hundreds of planets so far uncovered around otherstars, Gliese 581c is the best candidate for habitation. It could conceivablyboast such terrestrial amenities as liquid oceans, a benign atmosphere, andplate tectonics to churn metal ore close to the surface, useful for anyadvanced beings with a penchant for technology.

Theconditions for life could be there, but is life itself? As yet, there's no wayto know unless the planet has spawned beings that are at least as clever as weare. As part of the SETI Institute's ProjectPhoenix, we twice aimed large antennas in the direction of Gliese 581,hoping to pick up a signal that would bespeak technology. The first attempt wasmade in 1995, using the Parkes radio telescope in Australia, and two yearslater additional observations were undertaken using the 140-foot antenna inGreen Bank, West Virginia.

Neithersearch turned up a signal. But of course, the extraterrestrials might have beenoff the air when we were listening. Maybe their transmitter power wasinsufficient for our receivers, or perhaps the bandwidth we covered, from about1,200 to 3,000 MHz, was the wrong part of the dial. There are many ways notto find an alien broadcast, but the Allen Telescope Array, now being built,will greatly improve our ability to more thoroughly scrutinize this world - andhundreds of thousands of others.

Gliese 581is, as astronomical distances go, relatively close: only 20 light-years away. It'sone of the few star systems which, if inhabited, might provoke conversation. Asimple exchange, along the lines of "how are you?" followed by "fine,and you?" would require a mere four decades. Tedious, but not unthinkable.

However,irrespective of whether the world orbiting Gliese 581 is host to chatty beingsor not, its discovery is highly suggestive. In the mid-twentieth century,astronomers debated whether planets were extraordinarily rare or as common ascrickets. We now know the latter is true, and the number of planets in our owngalaxy could easily tally in the hundreds of billions. This latest discovery isa strong hint that a great number of these could be carpeted in the dirtychemistry we call life. Earth may be unique, but it might not be miraculous.

Seth Shostak is an astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, who places a high priority on communicating science to the public. In addition to his many academic papers, Seth has published hundreds of popular science articles, and not just for Space.com; he makes regular contributions to NBC News MACH, for example. Seth has also co-authored a college textbook on astrobiology and written three popular science books on SETI, including "Confessions of an Alien Hunter" (National Geographic, 2009). In addition, Seth ahosts the SETI Institute's weekly radio show, "Big Picture Science."