Curiosity Rover Spies Sand Dunes on Mars & Ancient Freshwater Deposits (Photos)

Curiosity's First 5 Years

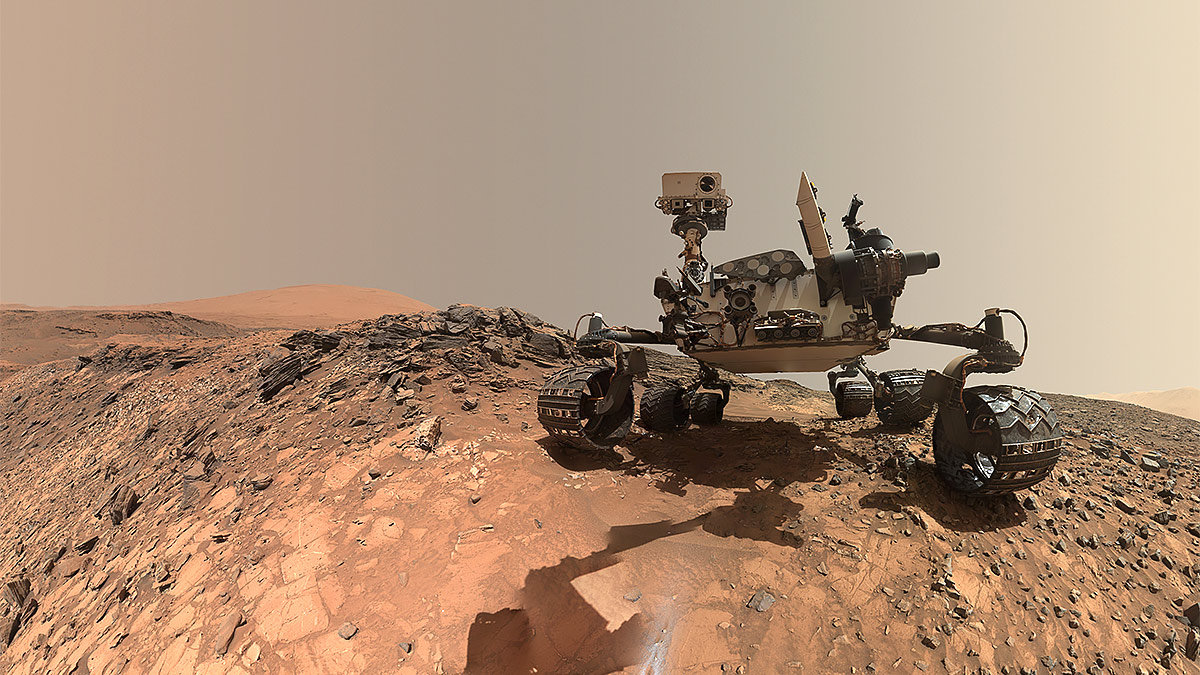

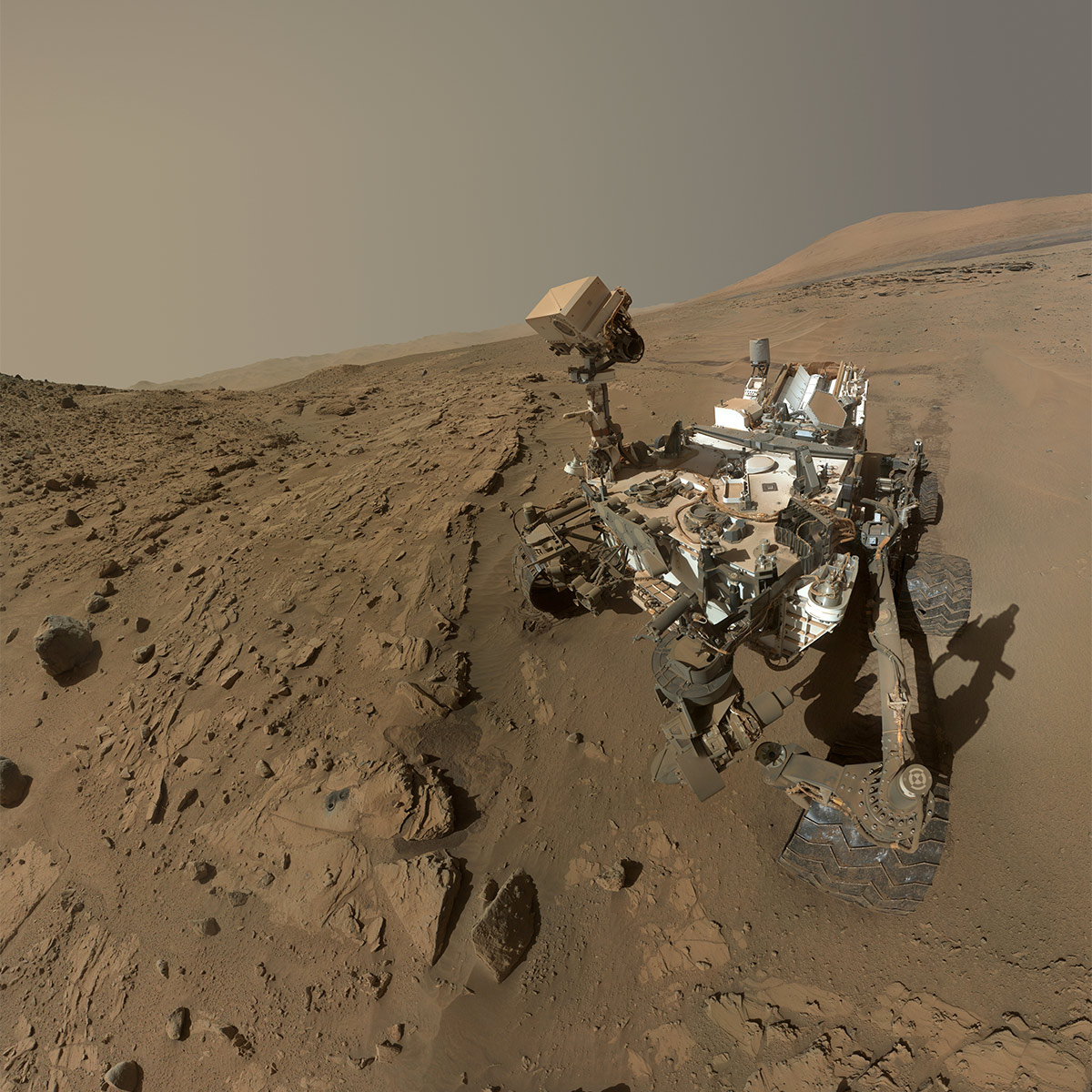

The Curiosity rover's first five years on Mars have been full of drama and scientific accomplishment. Within months of its hair-raising landing inside the huge Gale Crater on the night of Aug. 5, 2012, Curiosity had found evidence of an ancient Martian lake that may have been hospitable to microbial life billions of years ago — a discovery that fulfilled the rover's major goal of determining whether or not the Red Planet has ever been habitable. The six-wheeled robot then began making its way toward the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons) to study the layers in the mountain and track the area's geologic history.

While the mission has been full of successes, Curiosity has had some trouble with its wheels. Initially, the wheels were deteriorating faster than expected on the tough Martian terrain, but NASA modified the rover's driving style, taking it along gentler routes. This has slowed the damage, though wheel wear continues. The rover team is also troubleshooting an issue with Curiosity's drill, which has not been used since December 2016.

In the last few months, Curiosity has moved on to a new ridge on Mount Sharp and is trying to learn more about the environment there. The next few slides show the rover's journey around this feature, which mission scientists have dubbed Vera Rubin Ridge.

Mount Sharp and Vera Rubin Ridge

In the tradition of Earth explorers, members of the Curiosity team routinely name the landmarks that they come across — anything from rocks to ridges. While these monikers generally don't become "official" names recognized by the International Astronomical Union, they serve as useful guideposts when describing local features.

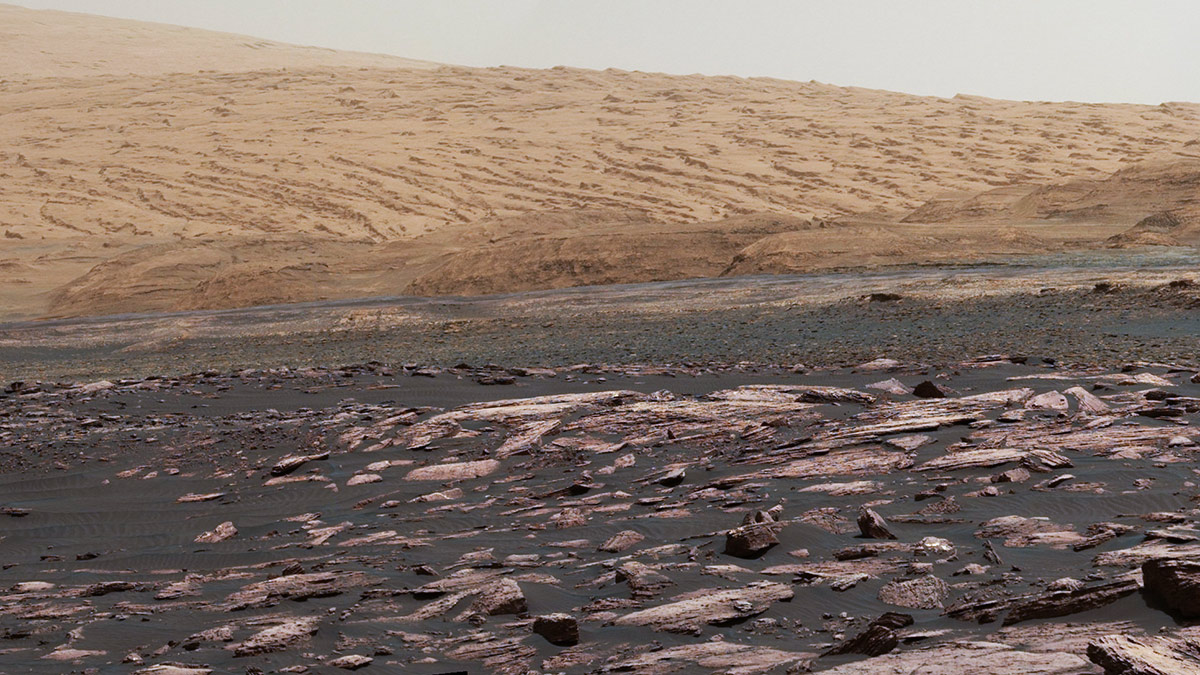

Here is a view of Vera Rubin Ridge, which was named after the late Vera Cooper Rubin, an astronomer whose observations helped provide evidence for dark matter in the universe. The eight-story ridge features an iron-oxide mineral called hematite that is known to form in wet conditions. (Hematite has been found in other locations on Mars by NASA's Opportunity and Spirit rovers.)

Layers on Mars

Curiosity's first job at Vera Rubin Ridge involves looking at sedimentary structures in the wall, but there will be other tasks as well, mission team members said. The rover will also look at a "boundary zone" between the ridge and the Murray formation, a lower geological unit that Curiosity has been studying since 2014. Specifically, geologists are curious to find out if the hematite in the Murray formation and Vera Rubin Ridge share similar histories.

"We want to determine the relationship between the conditions that produced the hematite and the conditions under which the rock layers of the ridge were deposited," Curiosity science team member Abigail Fraeman, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "Were they deposited by wind, or in a lake, or some other setting? Did the hematite form while the sediments accumulated, or later, from fluids moving through the rock?"

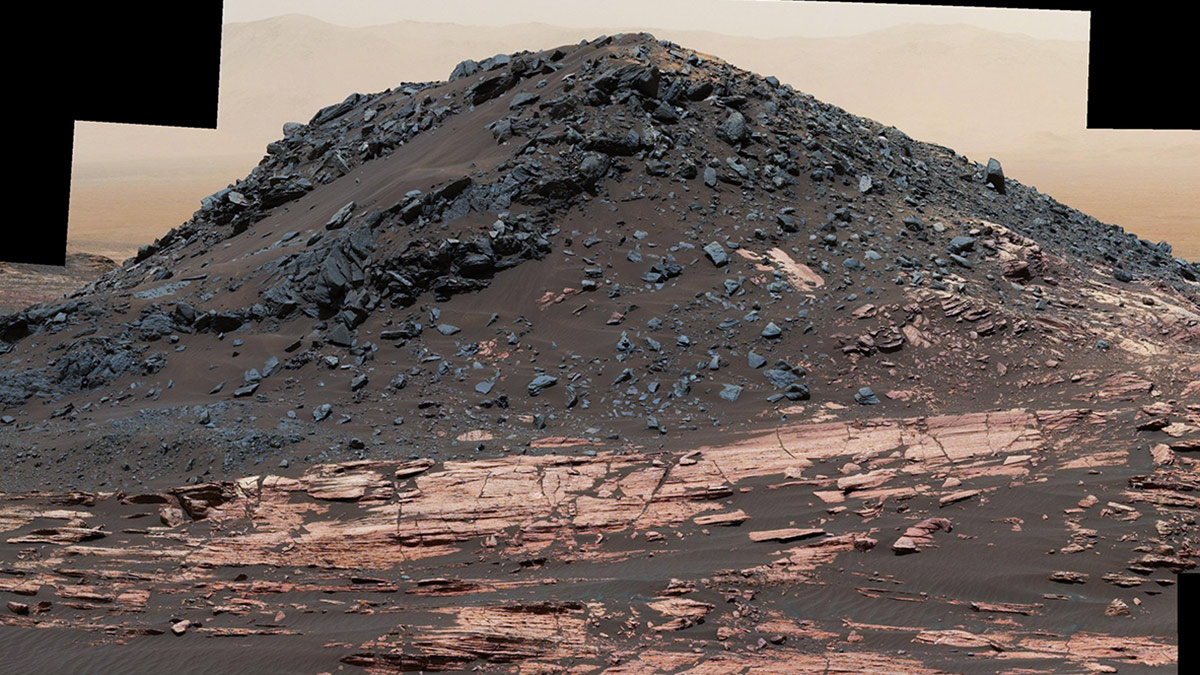

Ireson Hill

This dark hill is about 16 feet (5 meters) high and nicknamed Ireson Hill. Curiosity took this image at the Murray formation in February 2017 while studying a linear sand dune. Curiosity made a couple of visits to this formation a few months ago to look at some of the individual rocks and minerals, mission scientists said.

This previous work included an investigation of "Quimby," a rock that may have fallen off the top of Ireson Hill, and study of a target in the bedrock nicknamed "Quoddy." Curiosity captured close-up images and panoramic photos in this area, and also performed chemical and spectroscopic analysis, NASA officials said.

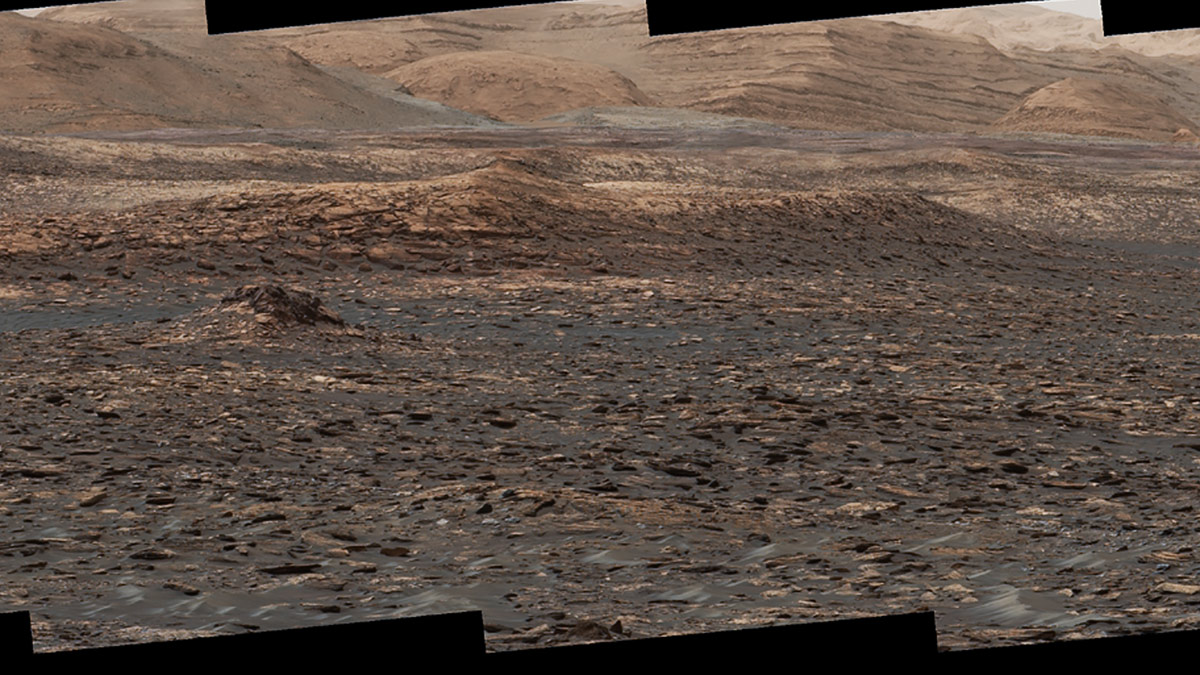

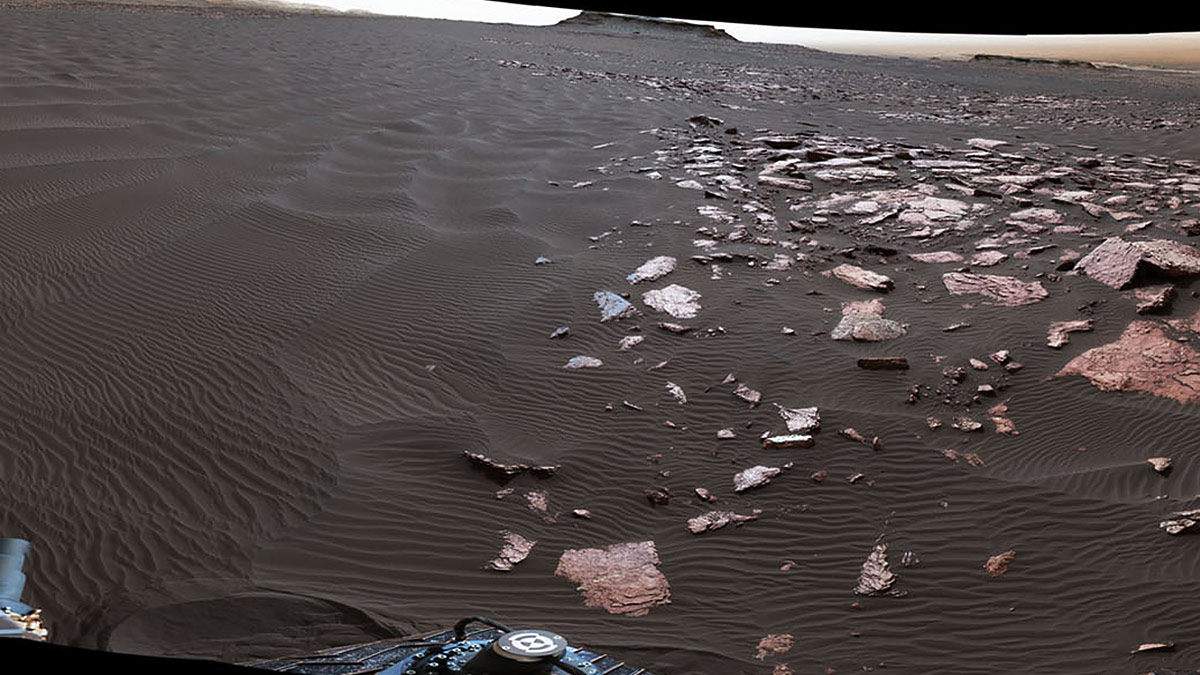

Dunes on a Mountain

One of Curiosity's ongoing science targets is active sand dunes; mission scientists want to learn more about how these transient features move across the Martian surface. This dune is nicknamed Nathan Bridges Dune after a planetary scientist who led the Curiosity team's dune campaign prior to his death in 2017.

In 2015, Curiosity data showed a dune surprise: It turns out that there is a kind of dune on Mars that does not exist on Earth. Due to Mars' thinner atmosphere, the Red Planet can support a kind of mid-size dune that falls between the small ripples and the large dunes that are seen on both Mars and Earth, NASA announced at the time.

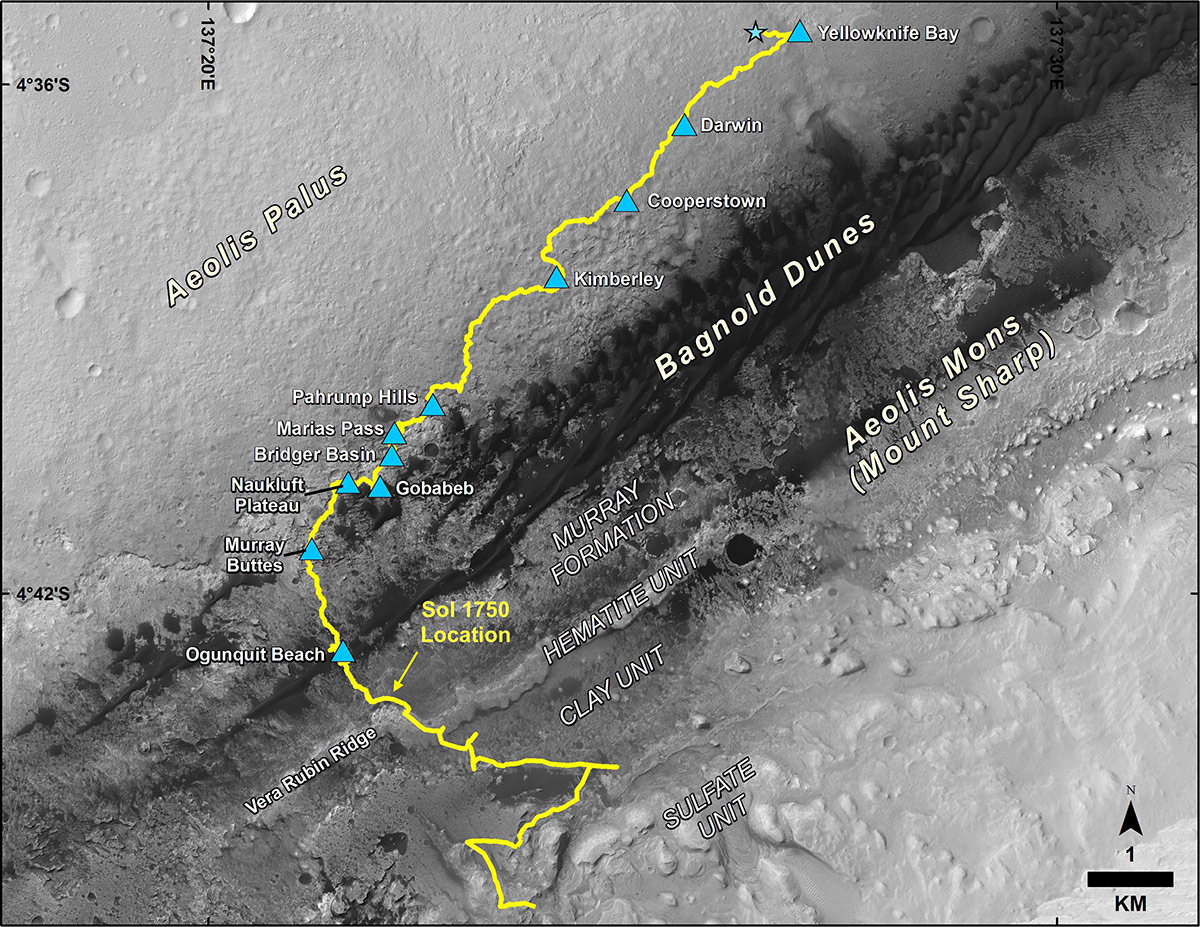

Curiosity's Travel

Curiosity has covered more than 10 miles (16 kilometers) on Mars in a little less than five years. (By comparison, the much smaller Opportunity rover — which has roved the Red Planet since 2004 — has traveled roughly 27 miles, or 45 km) This map, based on an image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, shows some of the highlights of Curiosity's travels since 2012.

The touchdown site, nicknamed Bradbury Landing, is marked by a blue star at the top. Blue triangles show where Curiosity stopped to examine features in Gale Crater and, starting with Pahrump Hills, on the flanks of Mount Sharp. Curiosity's position on July 9, 2017, is marked with the Sol 1750 label. A "sol" is a day on Mars, which is roughly 24 hours and 40 minutes in Earth time.

Looking Ahead

Curiosity's immediate priority will be learning more about the hematite at Vera Rubin Ridge, and whether the area's environmental history is similar to that of the older Murray formation. Specifically, the science team is curious to see if the waters that deposited the layers were more acidic at the higher elevation, NASA officials said.

The team will also attempt to determine whether a range of different oxidation levels, which could have served as an energy source for possible Mars life, existed at the site long ago.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.