Good for Life? Megatelescope Will Probe Newfound Worlds' Atmospheres

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Telescopes around the world (and orbiting it) have turned their gazes to the seven Earth-size planets of the TRAPPIST-1 star system — but it's an upcoming megatelescope that could reveal whether any of them have life-friendly atmospheres.

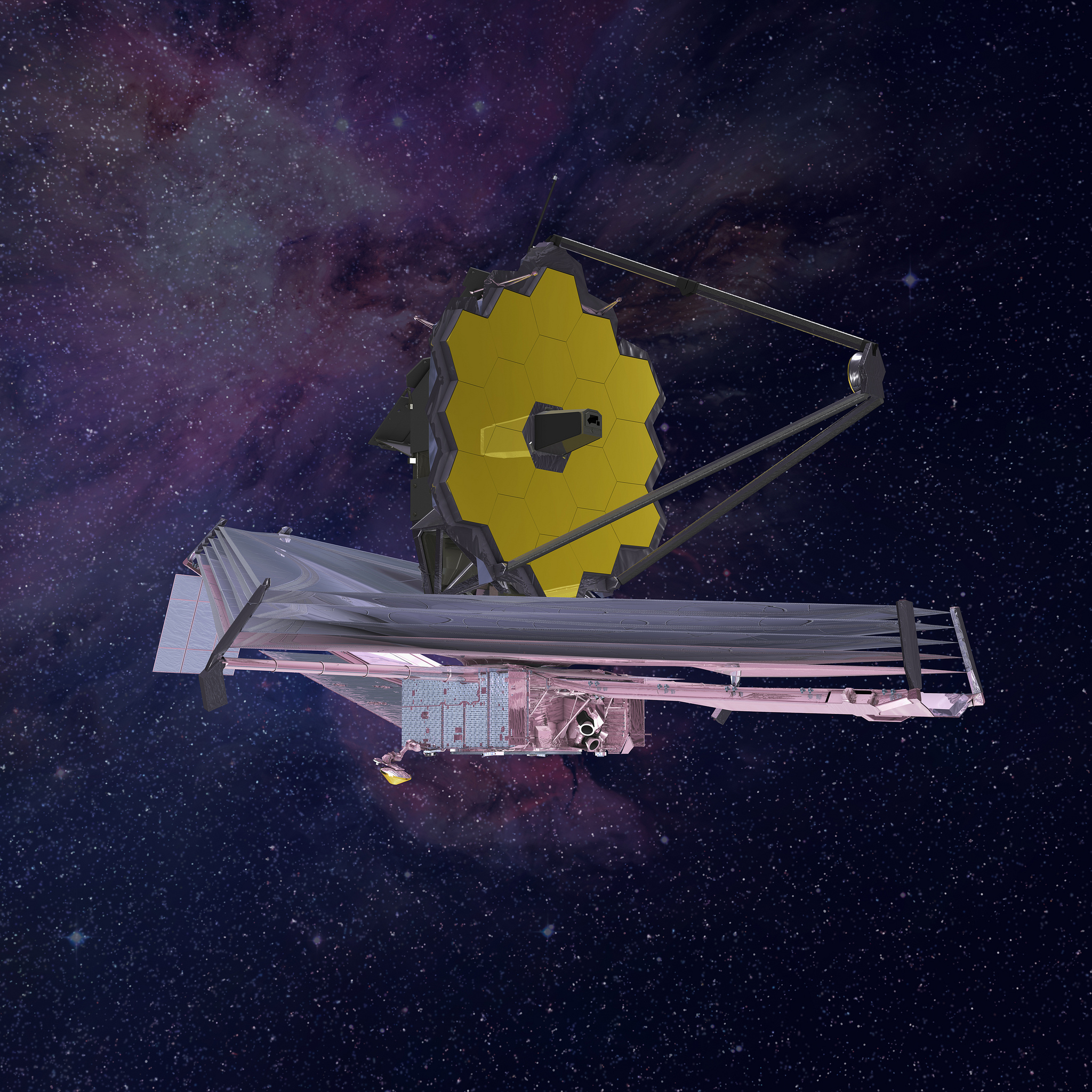

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), set to launch in 2018, is sensitive enough to identify the chemical components of the planets' atmospheres as the worlds pass in front of their star, NASA officials said.

"If these planets have atmospheres, the James Webb Space Telescope will be the key to unlocking their secrets," Doug Hudgins, exoplanet program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. "In the meantime, NASA's missions like Spitzer, Hubble and Kepler [telescopes] are following up on these planets." [TRAPPIST-1 System Has 7 Earth-Sized Exoplanets, 3 In Habitable Zone (Video)]

Researchers already knew that planets orbited the faint star TRAPPIST-1, based on the way it repeatedly dimmed and brightened, which suggested worlds were passing by it. And in 2016, a team announced that three planets had been found in the star's orbit. Follow-up investigations with ground-based telescopes suggested more planets might be there, but didn't give a clear picture.

This newest discovery, made by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, pins the number of planets at seven. Three of them travel in orbits that could potentially be friendly to Earth-style life, the researchers said, because these orbits put the planets at the right temperature to keep liquid water on their surfaces if they have atmospheres.

Spitzer, an infrared telescope had an advantage in looking at TRAPPIST-1 because the star is an ultracool dwarf: It's much brighter in infrared than in visible light, Shawn Domagal-Goldman, an astrobiologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a press briefing announcing the discovery of the planets.

From its view in space, Spitzer catalogued each of the planets as they passed by the star so researchers could work out their sizes and estimate their densities. The results of that estimation suggested the planets could be rocky, like Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Next up: James Webb

To find out if those three tantalizing planets in the "habitable zone" have atmospheres, researchers will turn to JWST. It's also an infrared space telescope, but is much more powerful than Spitzer. Researchers at Goddard are currently running tests on the completed telescope to prepare it for launch.

"These are the best Earth-sized planets for the James Webb Space Telescope to characterize, perhaps for its whole lifetime," Hannah Wakeford, also at Goddard, said in the statement. "The Webb telescope will increase the information we have about these planets immensely. With the extended wavelength coverage, we will be able to see if their atmospheres have water, methane, carbon monoxide/dioxide and/or oxygen."

The James Webb telescope will be able to illuminate these features of the planets because of how light interacts with planetary atmospheres. As the light from TRAPPIST-1 shines on a planet in its system, a small sliver of that light will pass through any atmosphere the world may have, altering the wavelengths of the light. If the planet is in between the star and Earth at that time, JWST can analyze that light to work out what (if anything) is in the planet's atmosphere, a process called characterization.

Signs of ozone and methane would be particularly exciting, as they would be possible signatures of life, NASA officials said, and the other chemicals could tell researchers about the planet's general conditions and the possibility that liquid water persists.

TRAPPIST-1 is perfectly placed for this type of analysis, the officials added: The system is relatively nearby to Earth, at 39 light-years away, and the star is small enough that it wouldn't overpower a signal from light passing by one of the planets in the habitable zone. That signal would be strong enough for JWST to pick up, the officials said.

"Two weeks ago, I would have told you that Webb can do this in theory, but in practice it would have required a nearly perfect target," Domagal-Goldman said in the statement. "Well, we were just handed three nearly perfect targets."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.