Satellites Track Glaciers Flows After Ice Dam Breaks

The breakup of an Antarctic ice shelf created runaway glaciers, swiftly dumping large amounts of ice into the ocean, according to a pair of new studies based on satellite data.

The process might be repeated on a larger scale if the climate continues to get warmer, causing global sea levels to rise significantly, scientists said.

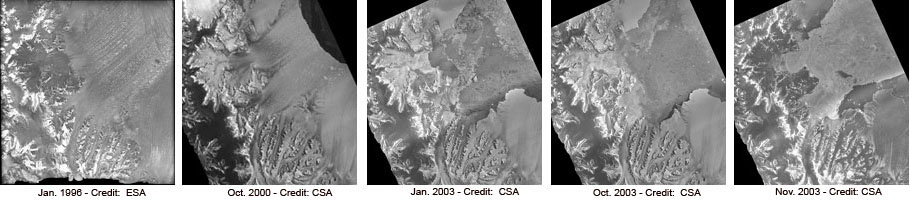

The Larsen B ice shelf broke free of the Antarctic Peninsula, a finger of the southernmost continent, in 2002. The collapse was attributed to a warming climate. Scientists have since watched nearby glaciers, which are like giant, slow-moving ice rivers, flow into the sea several times faster than before. They say the ice shelf, now gone, served as a dam.

The speed has caused the glaciers' thickness to drop by as much as 124 feet (38 meters) in one six-month period.

Scientists think the 15-mile-wide glaciers are thinning because the lower portions, near the sea, move more quickly, stretching the upper regions "like saltwater taffy," said Ted Scambos of the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The studies, announced yesterday, tracked the creation and movement of new crevasses generated by the stress.

Four glaciers previously held back by the Larsen B shelf traveled no more than 500 yards (460 meters) every year prior to the shelf's collapse, Scambos explained. Less than a year after the collapse, they moved along at a clip of 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) per year. That puts many more cubic miles of water into the ocean on an annual basis.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Ice that was on the continent itself rapidly flows into the ocean," Scambos said in a telephone interview. "It's very abrupt," he said of the change in the once-glacial pace.

The research also monitored two glaciers not related to the Larsen B shelf, and their speed has not changed during the study period.

"This study shows very clearly that glaciers which flow into ice shelves are partially controlled by the presence of the shelf, which acts as a kind of braking system," Scambos said. "Removing the shelf makes them speed up."

Because the glaciers are losing ice to the sea "at a rate which exceeds snowfall, there is excess water in the ocean from the glaciers, which means sea level is rising," said Eric Rignot, a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and leader of the second study. Both research efforts, performed independently, reached the same basic conclusions.

The amount of sea-level change associated with the Larsen B glaciers is less than a millimeter a year. But Rignot and Scambos say the process is a harbinger of what will happen when much larger ice sheets warm up.

"The point is that many other glaciers could do the same thing in the Peninsula, and eventually in Antarctica, in which case it won't be small," Rignot told SPACE.com. "What these studies are showing is that we should be concerned about that."

The research was funded by NASA and is detailed in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.