What the Ocean on Jupiter's Moon Europa Might Sound Like (Video)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

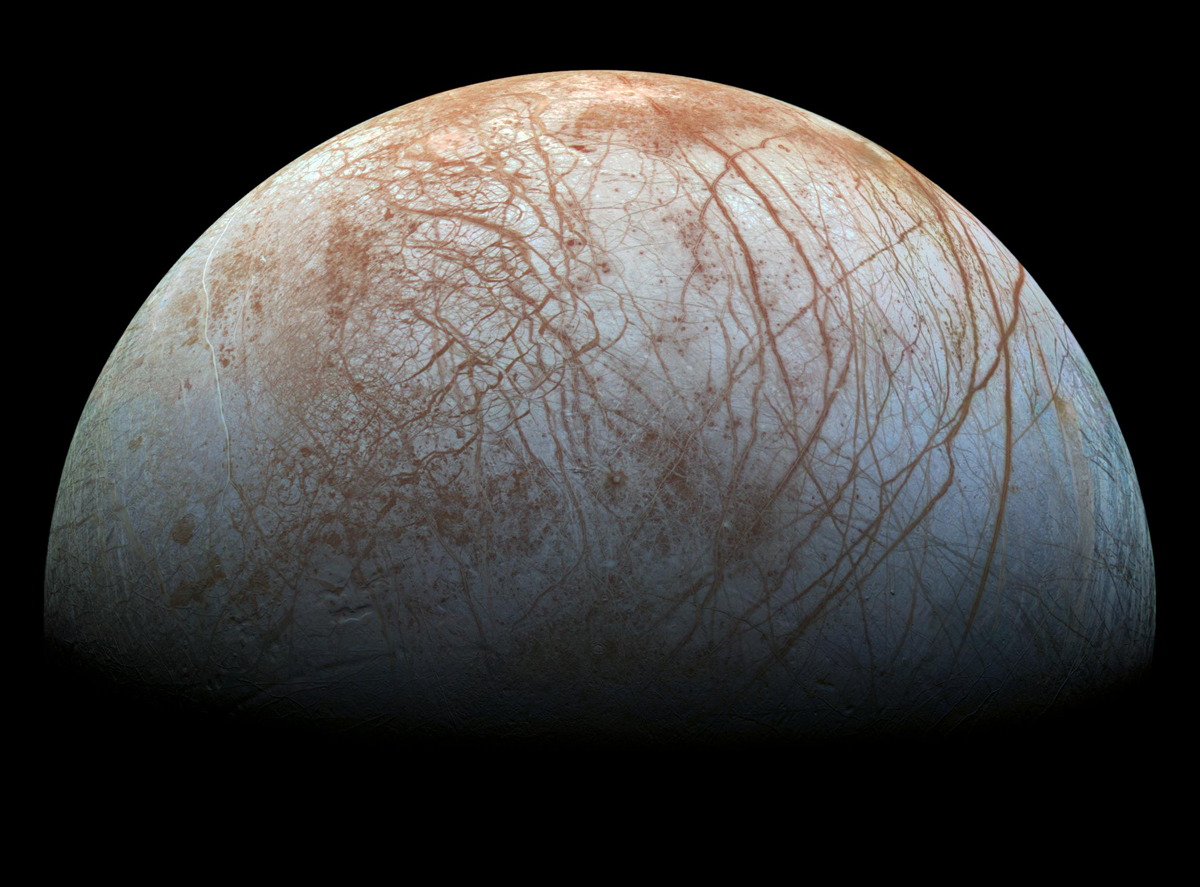

SAN FRANCISCO — The huge ocean that sloshes beneath the icy shell of Jupiter's moon Europa is likely a noisy place.

Cracking and sliding events within the shell — which, like the rest of Europa, is tugged hard by Jupiter's powerful gravity — probably create a sort of seismic hum that permeates the ocean, said Mark Panning, a geologist at the University of Florida. You can get a sense of that sonic background in this video, which features audio based on modeling work performed by Panning and his colleagues.

To be clear: This is not what you'd actually hear if you took a dip in Europa's frigid waters (after diving in through a very deep borehole, presumably). Panning and his team took 3 hours' worth of data from their seismic simulations, which contained information only up to 2 hertz — below the frequency that people can hear. They compressed the data into a 20-second clip and brought the frequencies into the audible range (using software provided by Georgia Tech researcher Zhigang Peng). [Europa May Harbor Simple Life-Forms (Video)]

Furthermore, these simulations don't provide a complete picture of Europa's soundscape, Panning stressed: They don't incorporate the contribution of water turbulence, which is the leading source of background noise in Earth's ocean. (The team aims to model turbulence effects soon, Panning said.)

Still, pretty cool.

But the researchers aren't doing this work — the results of which Panning presented here Wednesday (Dec. 14) at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) — for the gee-whiz appeal.

For the last several years, NASA has been developing a Europa flyby mission, which will investigate the 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) moon's ocean and its life-supporting potential over the course of dozens of close passes. Team members are working to get the flyby spacecraft ready to launch by 2022.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But late last year, Congress ordered NASA to add a lander component to the mission as well. The space agency is currently studying the best way to do that, and all signs point to two separate launches — one for the flyby probe, and one for the lander.

"It's essentially its own mission," Europa flyby mission deputy project scientist David Senske, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, told Space.com here at AGU, referring to the lander.

Whenever and however the lander gets off the ground, Panning hopes that a seismic instrument is on board. Such gear would allow researchers to get a better understanding of Europa's internal structure, he said.

And that's where the work by Panning and his team come in. A better picture of the ocean's ambient noise will help researchers design better seismic equipment and could provide other benefits as well, Panning said.

"It's going to guide instrument choice, and it could even help guide landing-site selection," he told Space.com at AGU.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.