Russia's Soyuz Spacecraft Marks 50 Years Since First Flight

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It launched under a different name and was not officially disclosed until almost two decades later, but Russia's first Soyuz spacecraft lifted off into history 50 years ago Monday (Nov. 28).

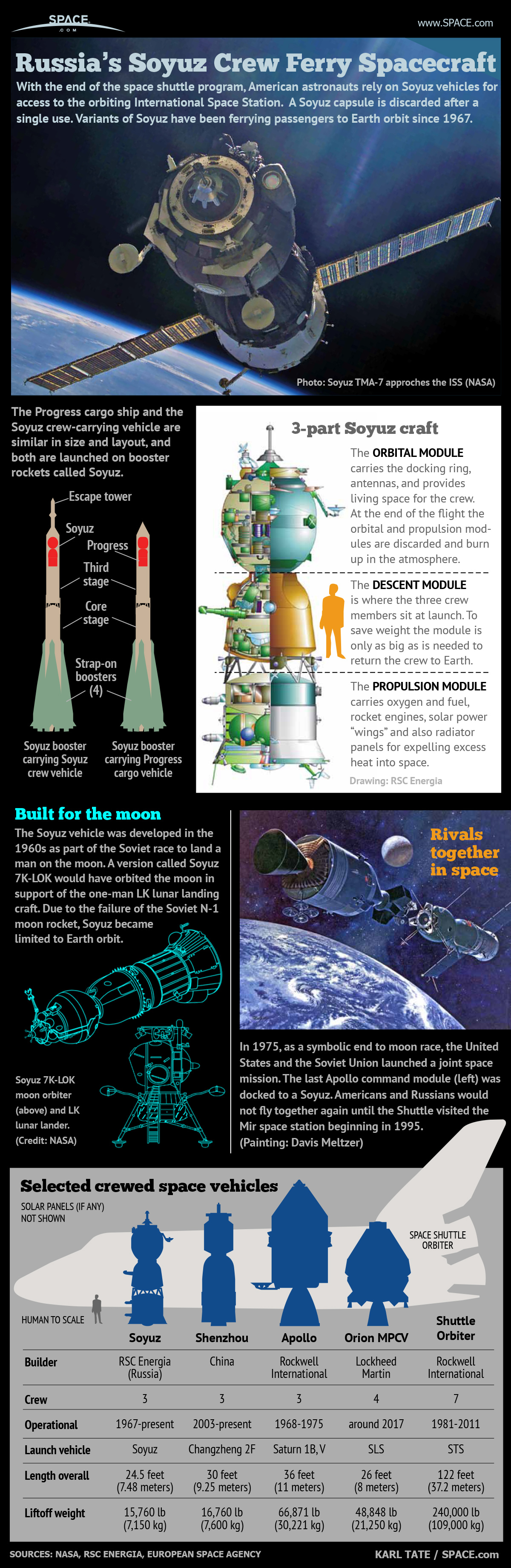

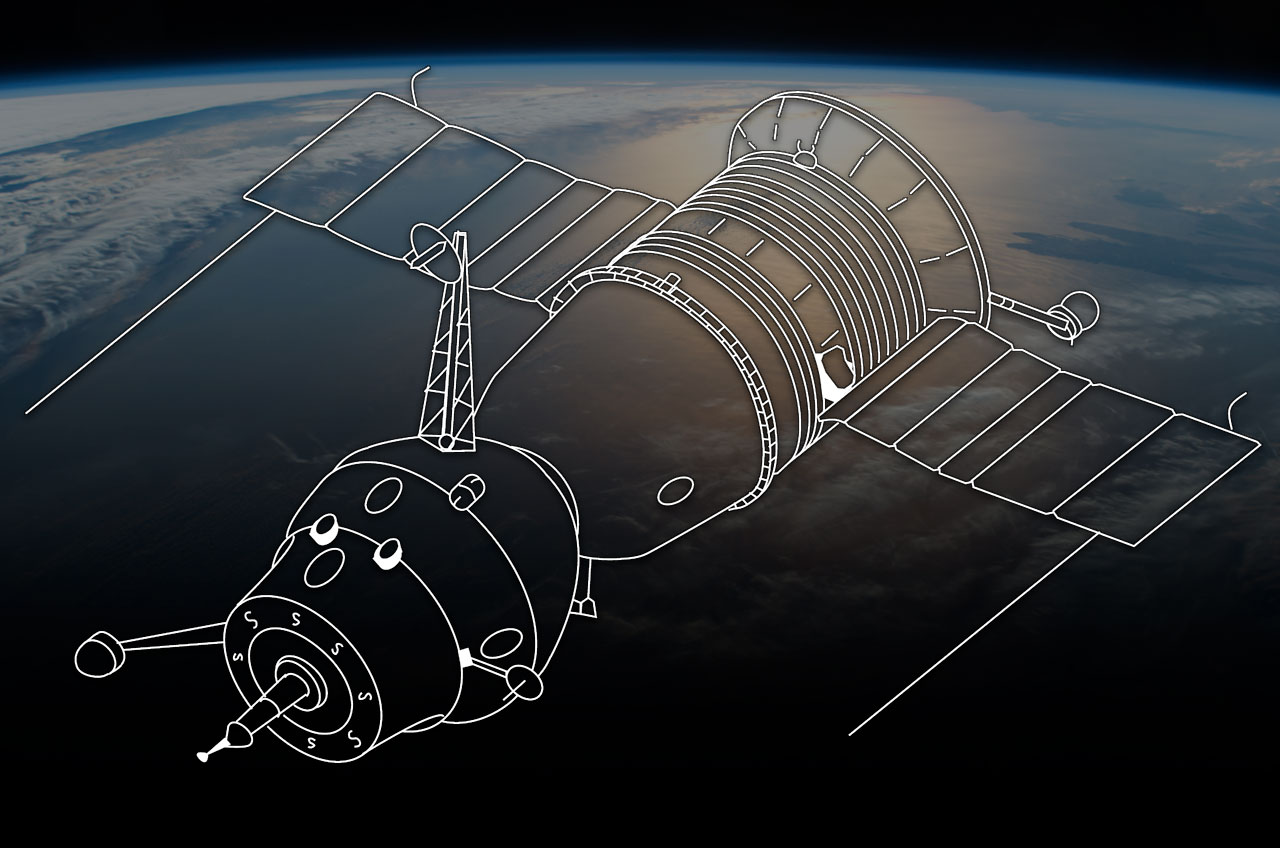

The Soyuz, which became the former Soviet Union's third class of crewed transport spacecraft and is still used today to take cosmonaut and astronaut crews to the International Space Station, first flew under the intentionally nondescript title "Kosmos 133" on Nov. 28, 1966.

The less-than-successful, 34-orbit uncrewed maiden mission ended with the Soyuz's descent capsule self-destructing, instead of landing off-course in China. But that was only the last of its problems. [Russia's Manned Soyuz Space Capsule Explained (Infographic)]

Article continues belowOriginally slated to fly a fully automated rendezvous and docking with Russia's second Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft, to be launched the following day, Kosmos 133 lifted off at 4 p.m. Moscow Time (6 a.m. EST; 1100 GMT) from Site 31 at Tyuratam, now known as the Baikonur Cosmodrome, in Kazakhstan. The launch inserted the spacecraft into a 112 by 144 mile (180 by 232 kilometer) orbit, slightly lower than planned.

"We've been waiting for this to happen," Nikolai Kamanin, then-head of the Soviet cosmonaut corps, wrote in a diary entry describing the first two Soyuz missions (as quoted by historian Asif Siddiqi in his 2000 book, "Challenge to Apollo"). "Today and tomorrow will see launches on which the immediate future of our space program will hinge."

Almost immediately though, flight controllers knew that the missions would not go as planned. Upon separating from its booster, the Kosmos 133 spacecraft's main orientation engine system lost pressure in its fuel tanks.

"Within less than 15 minutes, all or most of the propellant in the system had been used up, sending the spacecraft into a slow rotation of two revolutions per minute," Siddiqi wrote. "Given the engines were indispensable for attitude control during approach and docking, there was little hope of carrying out a docking with a second Soyuz."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The second Soyuz launch was called off (it would later fail to reach space during a launch attempt on Dec. 14, 1966, which ended with its escape system pulling the uncrewed capsule to a safe landing away from the pad), and attention turned to bringing Kosmos 133 back to Earth.

"The ballistic team quickly predicted that without additional maneuvers, the mission's orbit would decay [deorbit] after 39 orbits," wrote Anatoly Zak with RussianSpaceWeb.com. "It was now important to take the spacecraft under control as soon as possible."

Devising alternate methods of control, the flight managers attempted to use the vehicle's smaller thrusters to stabilize the spacecraft as the main engine performed short burns, instead of executing a 100-second firing under the nominal plan. These brief burns also ran into issues, though, cutting off early and placing the vehicle into the wrong orientation.

"The Soyuz apparently came close to deorbiting during the 33rd orbit on Nov. 30 ... but again, the engine burn was apparently cut short before completing the braking," wrote Zak. "Finally, the spacecraft plunged into the atmosphere during the 34th orbit of the mission."

The spacecraft's propulsion and orbital modules separated from the descent capsule as was planned, but then flight controllers then lost track of the plunging vehicle.

"Later, the State Commission ascertained that the descent trajectory had been too flat, and the capsule had begun to overshoot Soviet territory and head toward China," Siddiqi said. "The self-destruct system, consisting of 23 kilograms [50 pounds] of TNT, exploded automatically and destroyed the capsule."

"Debris apparently rained down on the Pacific Ocean, east of the Mariana Islands," he wrote.

The one day and 21 hour Kosmos 133 mission was not a complete failure, as the data collected during the flight led to improvements to the Soyuz spacecraft. [Space Travel: Danger at Every Phase (Infographic)]

After the second flight's launch failure the following month, three more uncrewed missions of the new spacecraft were launched in 1967 under the Kosmos title (two successes and one failure), prior to Soyuz 1 lifting off with cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov on April 23, 1967.

Tragically, the Soyuz 1 mission ended with the first in-flight fatality in spaceflight history, after a parachute failure led to the descent capsule slamming into the ground. The Soyuz returned to manned flight in October 1968, suffering only one more loss of crew on the Soyuz 11 mission in 1971 and an in-flight abort aboard Soyuz 18A (or Soyuz 18-1) in 1975.

To date, half a century after its first flight, Soyuz spacecraft have flown with 130 crews, flying Russian cosmonauts to Earth orbit and on missions to the Salyut and Mir space stations. The spacecraft comprised one-half of the world's first international mission, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, in 1975, and since October 2000, has been ferrying crews to the International Space Station.

Now its fourth generation, the Soyuz is slated to continue serving the Russian space program until the introduction of the Federatsiya ("Federation") crewed transport spacecraft targeted for 2023.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2016 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.