NASA's Human Mars Mission Will Require Living Off the Land

NASA's goals to land humans on Mars in the 2030s will require Mars settlers to "live off the land," just as the early European settlers did when they came to what is now the United States, according to a recent statement from the agency.

The practice of using local Martian resources for human survival — also known as "in-situ resource utilization" ISRU) — is something researchers are pursuing at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

"It was an incredible accomplishment when we went to the moon," said Bob Cabana, director of KSC and a former space shuttle astronaut, inthe statement. "We stayed for a couple of days and took some rocks home. We explored." [How Will a Human Mars Base Work? NASA's Vision in Images]

"But now," he said, "we want to be pioneers. As pioneers, we will create a sustained human presence in an ever more extreme environment."

These are some of the things KSC scientists are working on in the area of ISRU.

Durable machinery

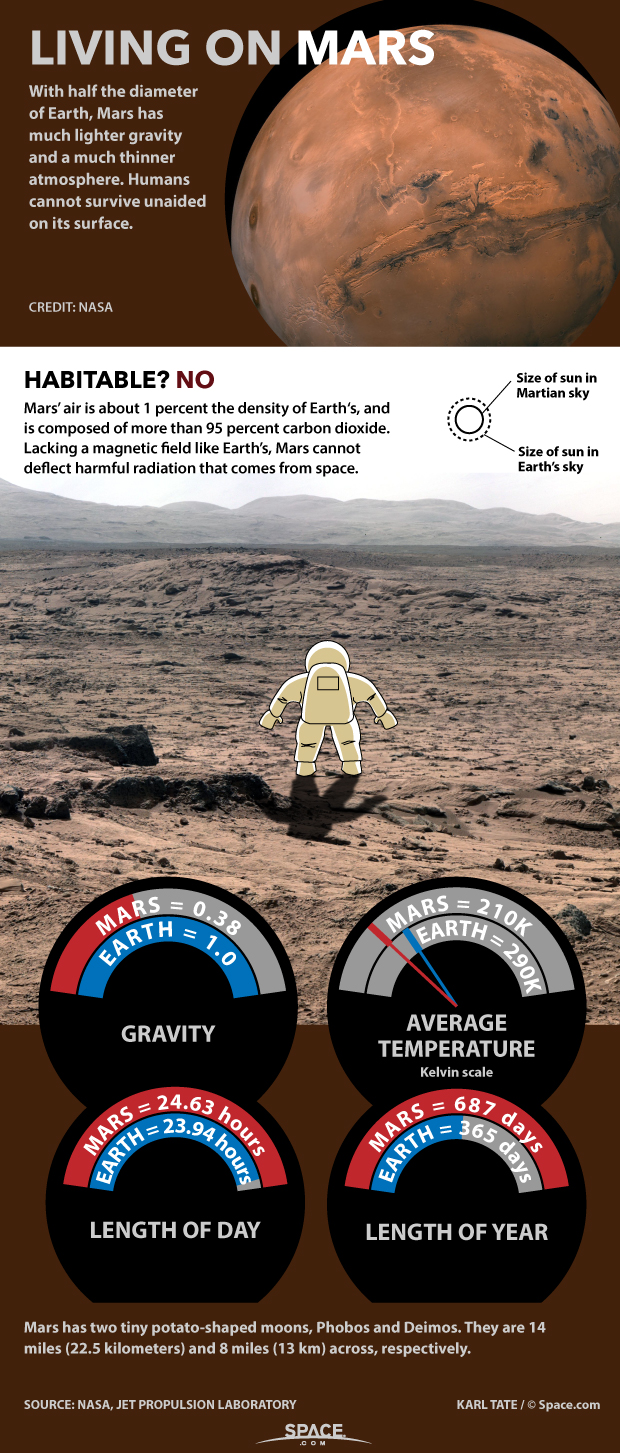

Mars has harsh conditions with wildly different temperatures, ranging from minus 195 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 126 Celsius) during winter at the poles to 70 F (21 C) during summer at the equator. The atmosphere is also 95 percent carbon dioxide. Earth’s atmosphere is primarily composed of nitrogen and oxygen.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"To (use ISRU resources) on a remote planet or an asteroid, the systems need to be very reliable," Jim Mantovani, a Kennedy planetary scientist and granular physics researcher, said in the statement.

Epic recycling

Some of the long-term aims at KSC include using resources on Mars to create propellant for rockets and other consumables for life support. But first, the agency needs to know where on Mars to look for those resources. NASA plans to send an orbiter to Mars with instruments to look for water in the regolith (loose rocks and dirt on top of bedrock) or soil, said Rob Mueller, a senior technologist at Kennedy's spaceport systems branch. A future lander would then survey the materials up close. A possible model for Martian mining missions would be NASA's Resource Prospector, a lunar robot that could launch in the 2020s, according to the statement. The prospector will try to locate specific resources at the lunar poles, and excavate samples of resources, such as hydrogen, water and oxygen.

Mining on Mars

NASA could dig for resources on the Red Planet using a robot called RASSOR, for Regolith Advanced Surface Systems Operations Robot. It will be designed to work in the lower gravity of Mars (62 percent lower than Earth's) and will pick up several small scoops of regolith. Then the material will be processed to remove water, hydrogen and oxygen, the statement said. Besides providing resources for people to live off of, the regolith could also be used to 3D print shelters and other things.

Growing crops

"Food is something we all depend on, and it's not going to be easy to get food out of regolith," Gioia Massa, a Kennedy project scientist that has worked on plant growth experiments on the International Space Station, said in the statement. "Right now, we pretty much take all our food along to the space station. But seeds are very small. Seeds are easy to take."

NASA researchers on Earth and aboard the station are working to find optimum growing environments for plants and crops in microgravity; they are testing the impact of factors that include lighting, nutrients and watering.

"There are a number of different types of plants we can grow [on the station]," Massa said. "We can start with produce that is just fresh that you can pick and eat. Other crops, such as potatoes, can be added depending on available time and resources."

Robots may also help tend to plants and crops so astronauts can devote their time to other activities.

'Trash to gas'

Kennedy is also working on ways to repurpose the waste from food, packaging and biological activities. A trash compactor being tested can take more than three quarts of material and burn it at 1,000 F (537 C). Possible byproducts of trash could include oxygen, water or rocket fuel, which would further reduce the amount of stuff to haul from home.

"It costs a great deal to launch a ton of payload beyond Earth orbit," Annie Meier, a chemical engineer at Kennedy, said in the statement. "So why not reuse it."

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.