E.T. Phones Earth? 1,500 Years Until Contact, Experts Estimate

SAN DIEGO — Aliens may be mediocre just like Earthlings, which could explain why humanity hasn't heard from advanced civilizations yet. If life on this planet develops at an average pace, rather than an exceptionally slow pace, then extraterrestrial life likely followed a similar path.

Like humanity, average civilizations have barely scratched the surface of galactic communication, so humans shouldn't start to worry about whether they're alone for another 1,500 years or so.

"Communicating with anybody is an incredibly slow, long-duration endeavor," said Evan Solomonides at a press conference June 14 at the American Astronomical Society's summer meeting in San Diego, California. Solomonides is an undergraduate student at Cornell University in New York, where he worked with Cornell radio astronomer Yervant Terzian to explore the mystery of the Fermi paradox: If life is abundant in the universe, the argument goes, it should have contacted Earth, yet there's no definitive sign of such an interaction. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

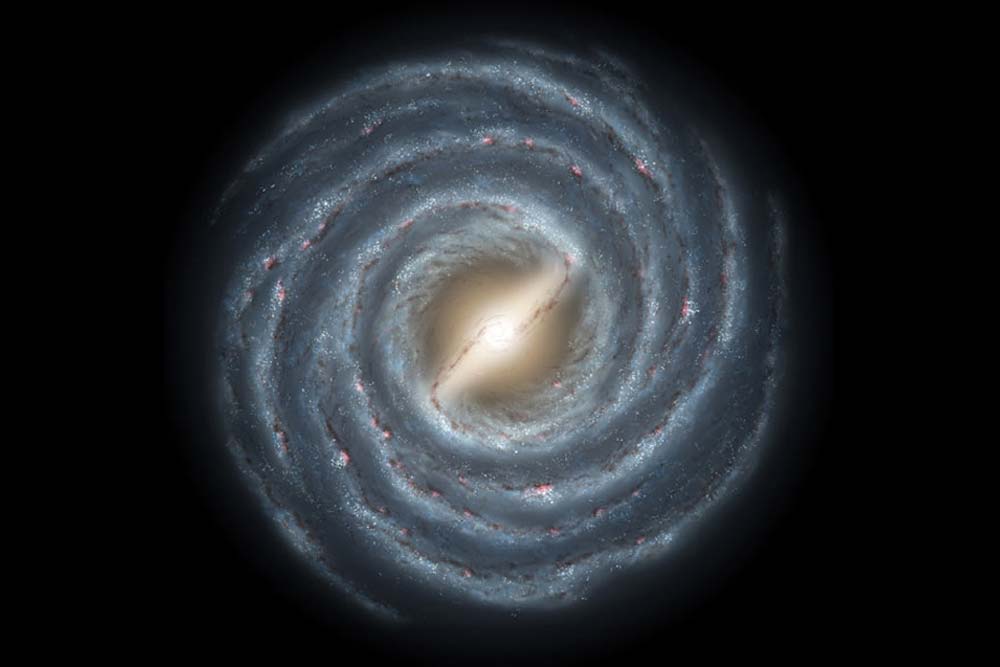

Solomonides said the enormous size of the galaxy means the silence comes as no surprise.

"Space is very big. It takes a long time to reach anyone, even at the speed of light," he said.

Silent space

When Enrico Fermi formulated his namesake paradox in the 1950s, planets around other stars were only hypothetical. Today, scientists suspect that nearly every sun has at least one if not more worlds, dramatically increasing the chances for life to have evolved throughout the universe. However, for some people, the lack of confirmed greeting from another civilization suggests that life may not be so common after all.

Solomonides applied the mediocrity principle — the idea that Earth's attributes are likely common in the rest of the universe, rather than unusual — to the Fermi paradox. Scientists think that Earth is an average planet around an average star, orbiting in an average place within an average galaxy.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There's nothing even remotely special about where we are in the universe, or even in the galaxy," Solomonides said.

The 1936 Berlin Olympic games broadcast was the first radio signal strong enough to leave Earth. Traveling at the speed of light, this program is the leading edge of a bubble of broadcasts racing outward through space from Earth. But that signal has managed to travel only 80 light-years from the planet.

Solomonides said advanced life elsewhere in the universe is unlikely to have arisen much before life on Earth. That's because bodies like those of humans require a mixture of the heavy elements produced over the lifetimes of stars, and it takes several generations of star formation to produce the necessary quantities. As a result, civilizations capable of communicating throughout the galaxy wouldn't have started out much earlier than happened on Earth.

Based on the assumption that life and technology on Earth should have evolved at a relatively average pace, not significantly faster or slower than for other civilizations, Solomonides calculated the communication bubbles that life would produce throughout the galaxy. He found that, as of today, only about a tenth of 1 percent of the Milky Way would be blanketed by signals. With those numbers, it's likely that Earth won't hear from other life-forms for another 1,500 years.

"There could be life everywhere in the galaxy, and we still wouldn't know it," Solomonides said.

In fact, "if we had been contacted by another civilization, we would actually be special."

That doesn't mean humanity should stop searching for signals or cut off broadcasts (though the rise of cable to carry television signals may mean that Earth is getting quieter anyway), Solomonides said. Instead, humans should keep broadcasting and listening in order to avoid missing the historic chance of contact, he said. People simply shouldn't expect results any time in the near future.

Even if, in the next 2,000 years, humans still haven't heard from other life-forms, that won't mean life doesn't exist throughout the galaxy, Solomonides said. He pointed out that communication requires the evolution of advanced life; molecular life won't be sending out signals, and so isn't considered in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Other scientists have suggested alien life may have evolved but then died out.

Another possibility is that advanced civilizations are unwilling to respond, because they'd rather avoid contact. After all, Solomnides said, Earth's first broadcast was Adolf Hitler's Olympics remarks.

"That's not really a great introduction," he said, wryly.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky