Jupiter-Size Alien World Is Biggest 'Tatooine' Planet with 2 Suns Ever Found

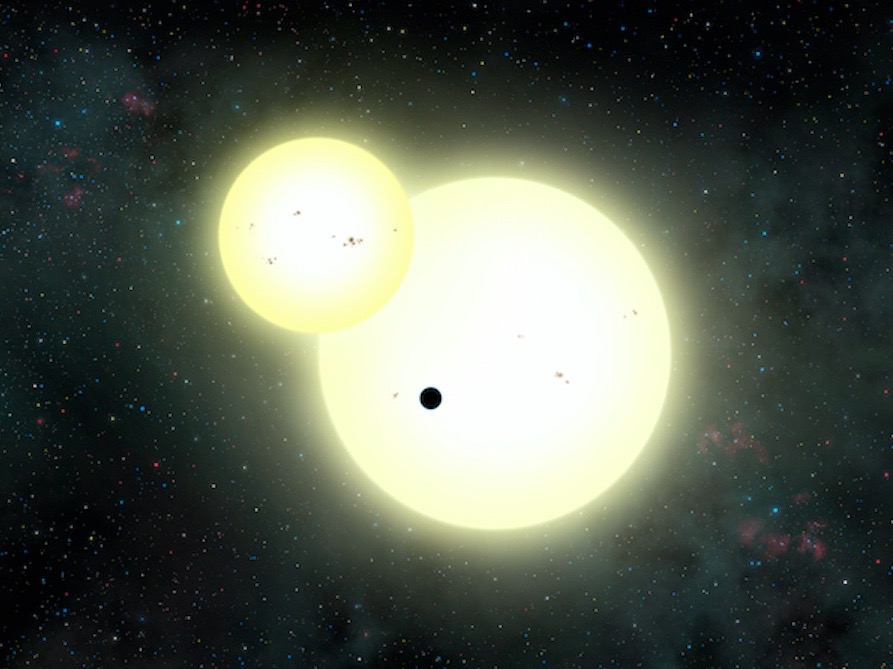

A newfound alien world is the biggest ever discovered that has two suns in its sky, like Luke Skywalker's home planet of Tatooine in the "Star Wars" universe.

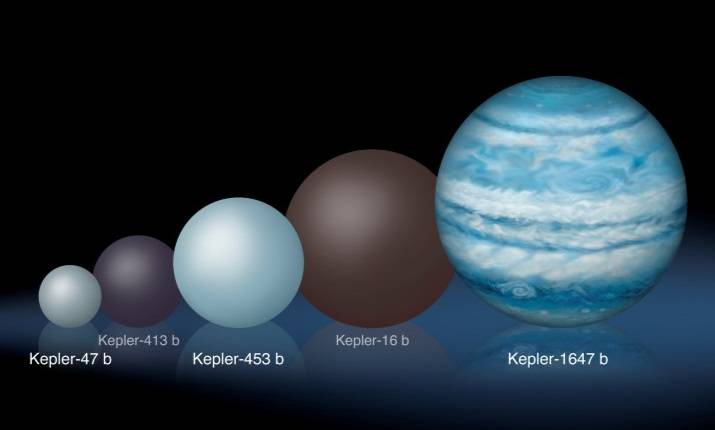

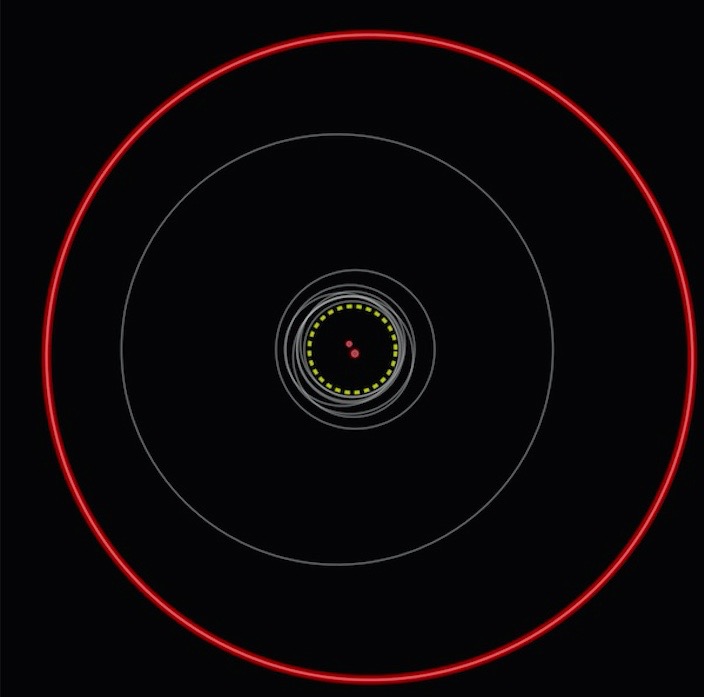

Whereas the fictional Tatooine is a small and rocky world, however, the real-life Kepler-1647b is a gas giant about the size and mass of Jupiter. In addition to being the biggest known two-star planet, Kepler-1647b also has the widest orbit, circling its host stars in 1,107 Earth days, astronomers said.

And the planet's intriguing characteristics don't stop there. Kepler-1647b also resides in its stars' "habitable zone," the range of distances at which liquid water could be stable on a world's surface. Kepler-1647b is a gas giant, so it doesn't have a surface — but any moons circling the huge planet could conceivably be capable of supporting life as we know it, study team members said. [10 Real Exoplanets That Resemble Star Wars Worlds]

Kepler-1647b was discovered by NASA's Kepler space telescope, which launched in March 2009 on a mission to determine how common Earth-like planets are throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

Kepler spots alien planets by noting the brightness dips that are caused when the worlds cross their host star's (or in this case stars') faces from the instrument's perspective. The spacecraft generally needs to observe three such "transits" to identify an exoplanet — which means that distantly orbiting worlds take longer to find.

"It’s a bit curious that this biggest planet took so long to confirm, since it is easier to find big planets than small ones," study co-author Jerome Orosz, an astronomer at San Diego State University (SDSU), said in a statement. "But it is because its orbital period is so long."

Kepler-1647b lies about 3,700 light-years from Earth, in the direction of the constellation Cygnus. The planet's two parent stars are about the same size as the sun — one is a bit bigger, and the other is a bit smaller — and they are both about 4.4 billion years old, study team members said. (The sun is 4.6 billion years old.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nearly half of all sunlike stars are part of two-star systems. Astronomers have found planets in a number of binary systems, but such worlds had previously all been Saturn-size or smaller, and had orbited relatively close to their host stars.

Kepler-1647b is "the tip of the iceberg of a theoretically predicted population of large, long-period circumbinary planets," co-author William Welsh, also of SDSU, said in the same statement.

The study team members announced their results today (June 13) at the 228th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in San Diego. Their paper has also been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Kepler's original planet-hunting observations ended in May 2013, when the second of the spacecraft's four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed. But scientists are still combing through the huge amounts of data gathered by Kepler, which has discovered more than 2,200 confirmed alien planets to date. The telescope also began searching for alien worlds anew (and observing a variety of other cosmic objects and phenomena as well) in 2014, after mission team members found a way to stabilize Kepler using sunlight pressure.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.