Top 5 Space Questions of 2015…with Answers! (Op-Ed)

Paul Sutter is a visiting scholar at The Ohio State University's Center for Cosmology and Astro-Particle Physics (CCAPP). Sutter is also host of the podcasts Ask a Spaceman and RealSpace, and the YouTube series Space In Your Face.

Because of my Ask a Spaceman podcast, speaking events and people sitting next to me on long flights, I get a lot of questions. Sometimes they're even about space. I love getting new questions and hearing what people are curious about. I've narrowed down all the questions I got this year into my favorite top five. Here we go!

Is the light from a supernova dangerous?

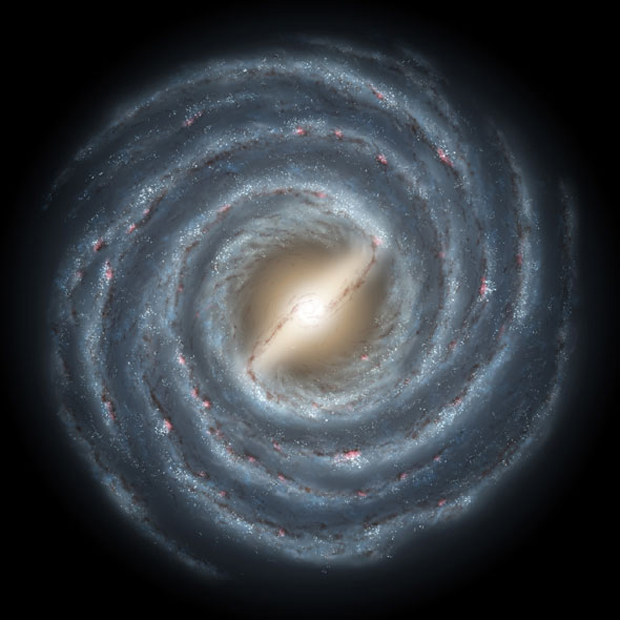

It depends on what you mean by "dangerous." If you mean "can kill you in an instant without any effort", then…yes, it's dangerous. A single supernova explosion can outshine an entire galaxy. Yes, you read that right. For a few days a single dying star is brighter than hundreds of billions of suns shining in unison. You think a sunburn is bad? Maybe a few blisters? You won't be able to pack enough SPF to cover your back if you're too close to a supernova going off.

It's not just the ultraviolet radiation. There's an unhealthy dose of X-rays and gamma rays, too. And, let's not forget, the sheer bulk of material ejected out into deep space at nearly the speed of light (in scientific terms, the explosion). After awhile, the supernova remnant calms down from "insanely dangerous" to "pretty dangerous," but the surrounding region of space persists as a galactic Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, awash in radiation and radioactive elements.

Please take this Public Health Advisory seriously: do not go near any supernovae.

Is an alien invasion possible?

Lots of things are possible, loosely using the word possible. It's possible that the atoms of the Earth spontaneously reorganize themselves and create a black hole. It's possible that this article will have 10 billion unique views. It's possible that intelligent aliens will construct a spaceship, travel across the gulf between the stars, find Earth, land here, and D-day us.

Possible, yes. Probable, no.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Let's look at the distances first. I don't think people really get — like in-your-bones get — just how far away stars are. Think of all the work it's taken to get to the moon, or to hurtle a piano-size probe to the lonely reaches of space near Pluto. If we wanted to send New Horizons to some truly new horizons, like the nearest star, it would have to go around 7,000 times farther than it is now. No, I did not add an extra 0 just for fun. And just to reach Pluto, New Horizons took around 9 years. Let's just say it's not easy to go interstellar.

Second, what do we have to offer? If aliens are able to harness the incredible resources and energies required to jump from star to star — why would they care about Earth? There's nothing here that isn't fantastically abundant anywhere else. After all, where do you think everything on and within Earth came from? Space. It came from space. "Hey, I know, let's build a mighty engine to hurtle us through the infinite darkness, and instead of exploring all the wonders the universe has to offer, let's land on a same-as-all-the-rest rocky planet and poke around," said no alien, ever.

Should we be worried about creating a black hole?

Let's just say that I sleep well at night knowing that my fellow physicists are busy slamming atomic nuclei together at near the speed of light. There are plenty of subatomic fireworks in those big accelerators, but probably not any black holes. We're not even sure we'll rip open such a hole in space-time — that prediction is based on a narrow class of speculative theories, which may or may not (let's just go with "not" for the time being) be true.

But what if we did make a microscopic black hole? Microscopic really means microscopic, not one of those stellar-mass ones roaming the galactic badlands or the monsters sitting in the hearts of galaxies. Black holes probably evaporate from Hawking Radiation, a hypothesized mechanism where black holes trap one of a pair of virtual particles, letting the other one free and thereby causing the black hole to lose mass. As soon as you make a teensy one — poof, it's gone. And if it survived? Well, to feed something actually has to get in its mouth, and if it's tiny it's not exactly Cookie Monster. Not sure about that analogy but you get the point. [Millions of Black Holes Seen by WISE Telescope (Photos)]

The other point is that it would take a long time to grow. Atom by accidental atom, molecule by stray molecule, it would take billions of years before you would start to get a mysterious sinking feeling.

Plus, Mother Nature sits back in wry amusement watching us smash our rocks together. You ever watch a toddler throw something? Adorable. Nature herself can accelerate particles to energies billions (literally!) of times higher than we can, and has been doing so for billions (literally!) of years. And the ground stays firm.

Could you travel through a wormhole?

Yeah, sure, whatever. You can travel through anything you want. But the thing has to exist in the first place. That's the tricky part. Wormholes are a valid solution to the equations of Einstein's general relativity — the foundation of our modern understanding of gravity, which tells us that matter and energy bend space-time like a fat dog on an old couch, and the subsequent warping of space-time informs matter to move over there rather than over here.

"Solution" is the key word here. General relativity (GR) is a (painfully complicated) set of mathematical equations. On one side you have the stuff in the universe, and on the other you have the description of the curvature. The usual question in GR is: for a given arrangement of stuff, how does space bend? But you can also go the other way: If I want to bend space like so, what kind of stuff do I need and where do I need to put it?

And so we ask: Can we give space-time a throat, so that it can swallow a spacecraft and pop it out somewhere else? What stuff do I need to manipulate space-time to make that happen? The answer: Wormholes are naturally unstable, unless you thread them with negative mass. Negative. Mass. Mass with a minus sign.

We can have negative energy and negative pressure — think Casimir forces or Dark Energy — and mass and energy are two sides of the same relativistic coin, but "negative mass" isn't exactly in the known rulebook for the universe. We don't see any around. We don't know how to make any.

Getting around that issue sends you right into the weeds of quantum gravity — which we also don't have a solution for. So wormholes could exist, but so far we don't know how they would. But if they did, you could travel down one just fine…maybe.

(Watch: I answer these questions and more at this live event!)

Will we ever run out of things to know?

I think by far this was my most favorite question I've gotten all year. I don't know how many times I've typed, said, or thought the phrase "…but we don't know." We know a lot, and we're learning more about the universe every single day. But there is so much we don't know, so much we don't understand, and so much that still boggles our poor beleaguered monkey brains.

Every day through constant hard work and sweat — and a little blood — we chip away at the universe, revealing just a tiny bit more. But every new answer comes with a dozen new questions. Every time the envelope is pushed the problem gets bigger. Every new discovery casts fresh light on problems old and new. It's a beautiful universe, and we'll never figure out all of it, which makes it even more beautiful. As scientists we find joy not just in the discovery but in the pursuit.

Oh, and the job security.

Learn more by listening to the episode "Question Bonanza!" on the Ask a Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to the people of Lima for the question that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter. Prior columns are available on Sutter's Expert Voices landing page.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.