Ancient Carbon Haze Offers Clues to Galaxy Evolution

Astronomers have detected carbon smog permeating the interstellar atmospheres of early galaxies, helping confirm that these ancient galaxies were mostly dust free.

The discovery sheds light on how some of the first galaxies to form in the universe grew and evolved, researchers said.

Gas and dust are the main components of the interstellar medium, the matter in galaxies that constitutes the building blocks of stars and planets. The gases hydrogen and helium make up 98 percent of all "normal" (i.e., not dark) matter in the universe. The other 2 percent — any elements heavier than helium, making up everything from dust to planets — was created from the fusion of hydrogen and helium atoms in the hearts of stars. [The History & Structure of the Universe (Infographic)]

Since dust formed only after the birth of the first stars, scientists expected that galaxies began nearly dustless, getting dustier as they evolved. However, confirming what the interstellar medium in early galaxies was like has been a challenge for researchers. If there was less dust, it would make starlight from early galaxies bluer, but there are many other effects that could have made this light bluer as well, said study lead author Peter Capak, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

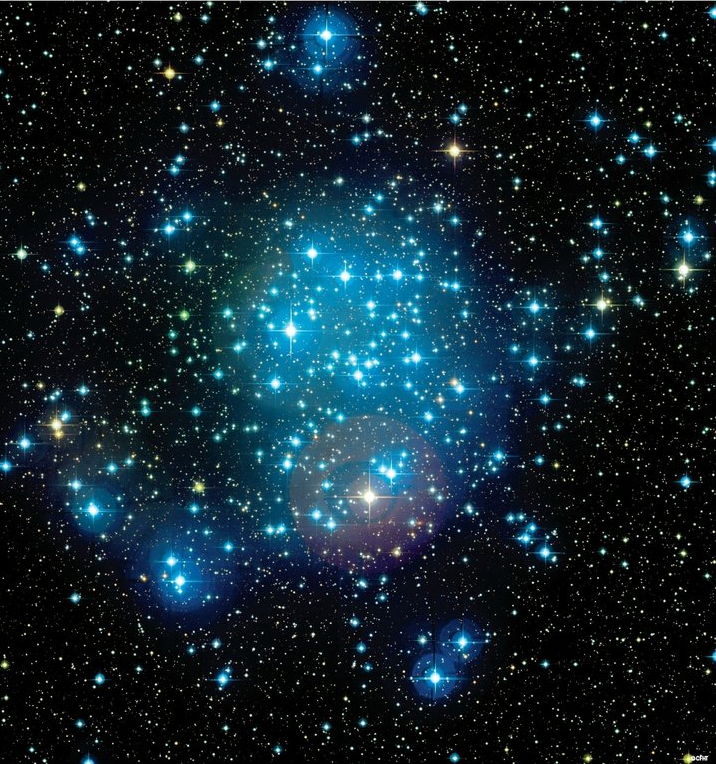

Now, using the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observatory in Chile, astronomers have confirmed that early galaxies apparently have less dust than more evolved galaxies.

"There is little dust in early galaxies about 1 billion years old, in the epoch of the first galaxies," Capak told Space.com. "We are starting to see the point where galaxies are truly primordial, some of the first to form stars."

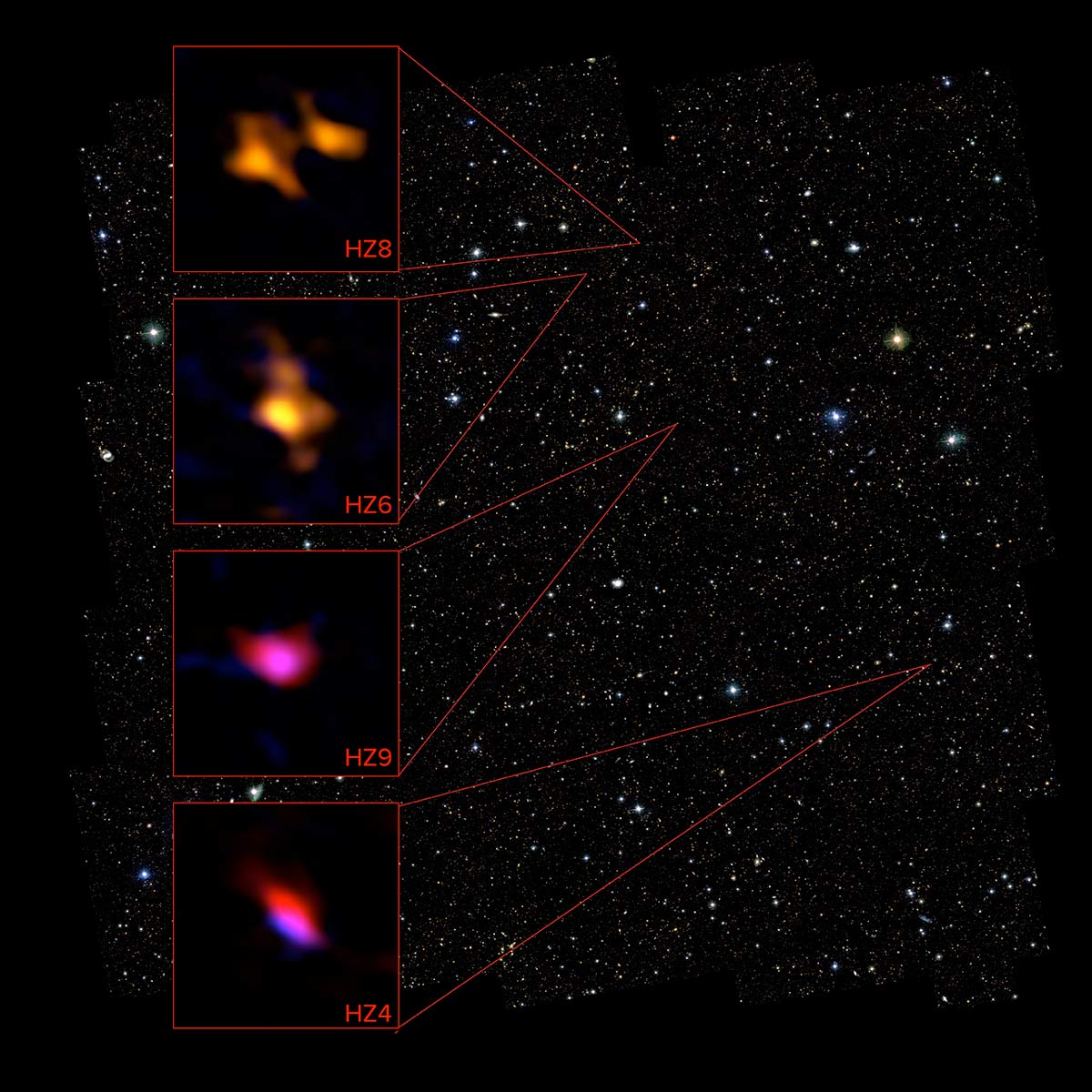

The researchers analyzed nine star-forming galaxies located about 13 billion light-years away from Earth. The scientists therefore viewed the galaxies when the universe was 1 billion years old or so, or only about seven percent of its current age.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team focused on the faint glow of ionized carbon. This element can become ionized, or electrically charged, due to the powerful ultraviolet radiation emitted by bright, massive stars. In the process, it will give off specific frequencies of radio waves.

Since carbon has a strong chemical affinity for other elements, binding to make simple and complex organic molecules, it does not remain in an unbound, ionized state for very long. This means the radio glow of ionized carbon is probably a good marker for an early galaxy, which would possess much lower concentrations of the heavy elements that ionized carbon would bind to in later galaxies to form dust grains.

Prior attempts to detect the radio glow of ionized carbon in early galaxies had failed for nearly 30 years. Some researchers had speculated that a few billion years more were needed for stars to manufacture sufficient quantities of carbon to be seen across vast cosmic distances.

However, ALMA readily detected the haze of ionized carbon in these early galaxies. In comparison, similar galaxies existing about 2 billion years later had much less ionized carbon. Prior studies failed to detect this ancient radio glow, researchers said, because these studies focused on atypical galaxies undergoing mergers — dramatic activity that may have masked the faint signal from ionized carbon.

By analyzing how ionized carbon is moving in these early galaxies, astronomers can learn details about star formation at the time, Capak added. This, in turn, could help solve the mystery of how galaxies were able to reach the massive sizes they attained early in the universe's history, he said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (June 24) in the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us