Planck's Mystery Cosmic 'Cold Spot' May Be an Error

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

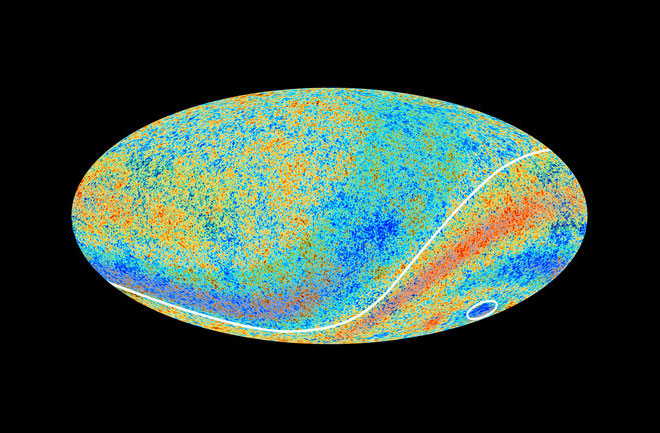

The European Planck space telescope detects very faint primordial radiation that was generated after the Big Bang — when the universe was only 380,000 years old. By creating a cosmic map of the slight variations in this cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation — variations known as "anisotropies" — cosmologists have been able to gain some clue as to the structure of the Universe nearly 14 billion years ago.

However, several anomalies in the CMB map have confused the scientific community; some mysterious features mapped by Planck don't agree with established theory as to how the Cosmos works. Is there some exotic new cosmology at play? Or are these features simply observational error?

NEWS: Universe Older Than Thought, New Map Reveals

One of the more exotic explanations for the cold spot is that it could be observational evidence for the "multiverse"— a hypothesis with roots in superstring theory where our universe exists in an ocean of other universes — and the cold spot is caused by a neighboring universe pushing up against ours. Unfortunately, the feature might not even be real.

"Using new techniques to separate the foreground light from the background, and taking into account effects like the motion of our Galaxy, we found that most of the claimed anomalies we studied, like the cold spot, stop being problematic," said lead researcher Anaïs Rassat, of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

ANALYSIS: Will Science Burst the Multiverse's Bubble?

Rassat’s team’s work has been published today (Aug. 4) in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

When mapping such faint radiation that has been traveling through space-time for billions of years, it is difficult to separate the primordial signal from other microwave sources. Our galaxy, for example, swamps the universal vista with microwaves and, as we live inside the galactic disk, our microwave view is dominated by Milky Way emissions. It's a thick cosmic fog that needs to be subtracted.

Through complex algorithms and foreground emission subtraction techniques, these extraneous microwave sources can be effectively removed. But Rassat's team gave the data another pass, correcting for the motion of our galaxy and other impacts such as gravitational interference and distortions in the radiation itself.

Although this study appears to have corrected for previously overlooked effects in Planck observations, some anomalies remain in the data, leaving room for some of the more exotic hypotheses about the origin and nature of our universe. But as for Planck's "cold spot," that mystery might be down to observational error and not something real.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.