Venus Moves into the Morning Sky: How to See It

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

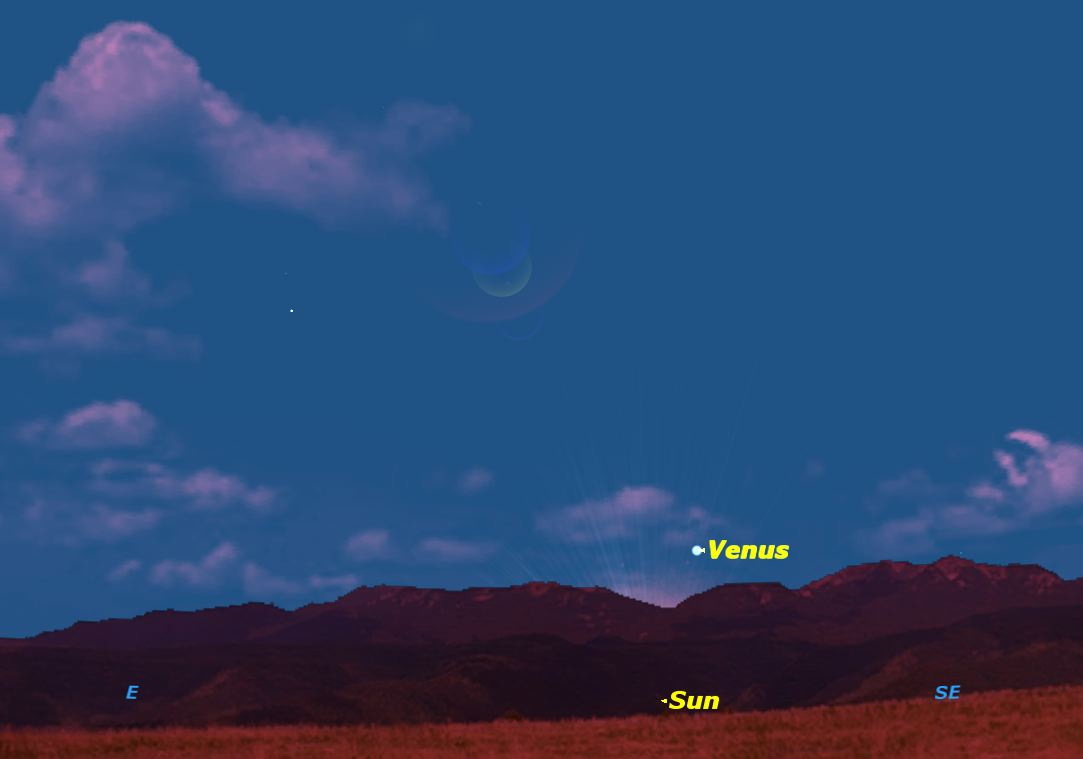

What a difference a week makes. If you were looking up just after sunset this week, you may have caught a glimpse of Venus setting just after the sun, weather permitting. But try it again at the same time next week, and Venus will be gone.

But if you look just before sunrise on Wednesday, Jan. 15, you'll see Venus rising just before the sun. So how does that happen?

On Saturday (Jan. 11), Venus will pass between Earth and the sun, an event scientists call an "inferior conjunction." A conjunction occurs when two celestial objects reach the same longitude and appear to line up. In the case of the planets Mercury and Venus, conjunctions with the sun can be either "inferior" (when the planet is on the near side of the sun) or "superior" (when the planet is on the sun's far side). [The Planet Venus: 10 Weirdest Facts]

Venus and the sun

The last time we had an inferior conjunction of Venus and the sun was on June 6, 2012. On that date, Venus actually passed in front of the sun's disk as seen from Earth, an event so rare that it happens less than twice a century. This was called a "transit of Venus."

But on Saturday, Venus will pass well to the north of the sun, so it will not be visible on the sun's disk by observers on Earth.

If you manage to spot Venus in the next night or two, take a look at it with binoculars. It should appear as a slender crescent, almost completely backlit by the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

See Venus on Saturday

An interesting challenge is to see how close to conjunction you can observe Venus. If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, have a clear view of very low horizon in both the east and west, and very clear skies, you might actually be able to observe Venus on Jan. 11 as both a morning and an evening star, because it will be passing north of the sun.

Very experienced observers might even try to spot Venus in a telescope within a day or two of conjunction.

This is very dangerous because the sun will actually be shining into the tube of the telescope. I managed such an observation on April 9, 1961, only 27 hours from conjunction, using an 8-inch reflector. At that time I saw Venus as a complete circle of light. Because the sun was almost behind it, the entire ring of its atmosphere was lit up. Warning: This is something only experienced observers should attempt, because there is great danger in accidentally getting the sun in the field of view, which might cause permanent blindness.

Editor's note: If you have snap an amazing photo of Venus, or any other night sky object, and you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.