Strange Super-Earth Planet Has 'Plasma' Water Atmosphere

A nearby alien planet six times the size of the Earth is covered with a water-rich atmosphere that includes a strange "plasma form" of water, scientists say.

Astronomers have determined that the atmosphere of super-Earth Gliese 1214 b is likely water-rich. However, this exoplanet is no Earth twin. The high temperature and density of the planet give it an atmosphere that differs dramatically from Earth.

"As the temperature and pressure are so high, water is not in a usual form (vapor, liquid, or solid), but in an ionic or plasma form at the bottom the atmosphere — namely the interior — of Gliese 1214 b," principle investigator Norio Narita of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan told SPACE.com by email. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

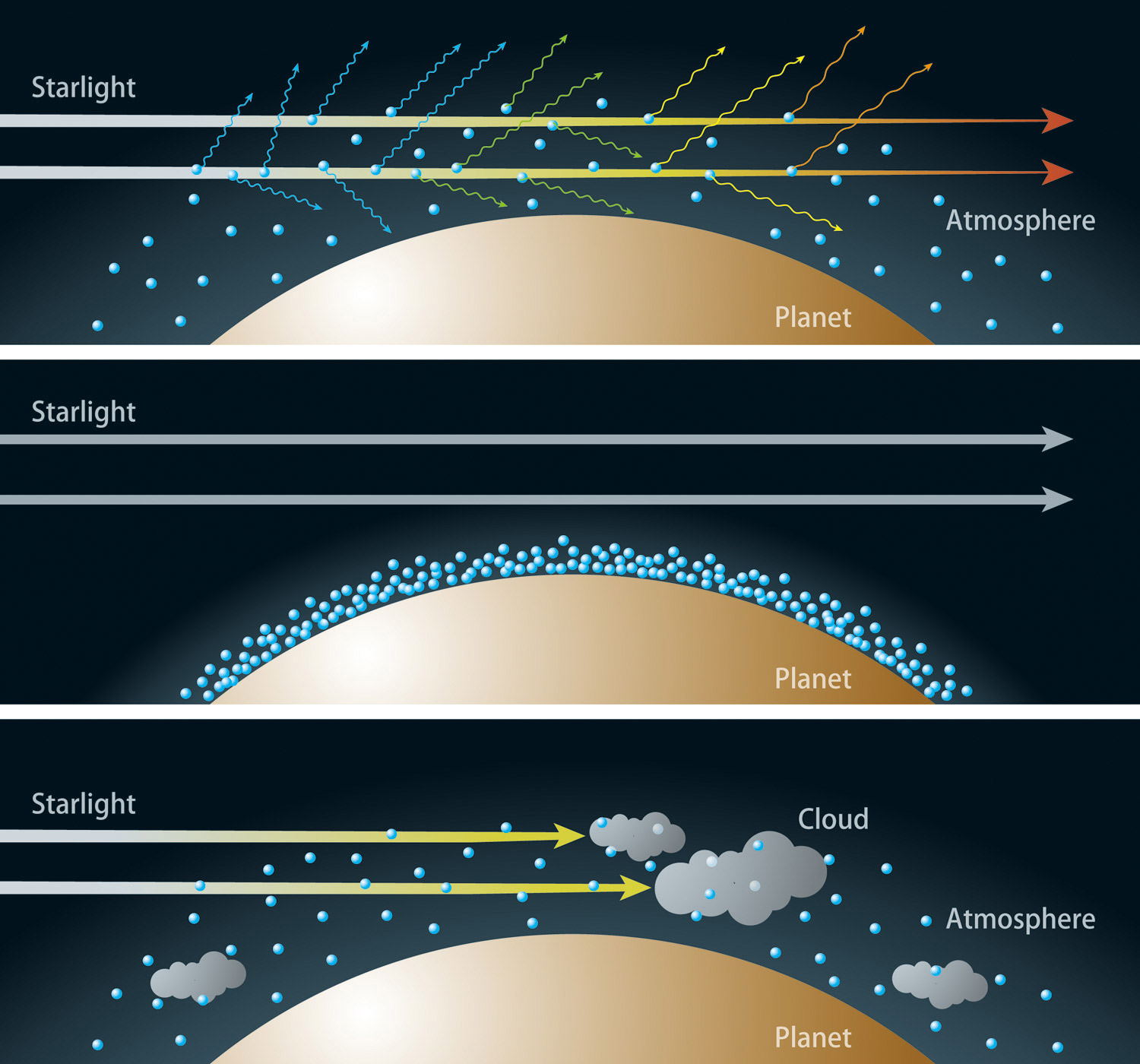

Using two instruments on the Subaru Telescope in Mauna Kea, Hawaii, scientists studied the scattering of light from the planet. Combining their results with previous observations led the astronomers to conclude that the atmosphere contained significant amounts of water.

A wellspring of exotic water

Located 40 light-years from the solar system in the constellation Ophiuchus, the planet orbits its cooler, low-mass M-type star once every 38 hours, 70 times closer than Earth is to the sun.

Its close proximity means that its temperatures reach up to 540 degrees Fahrenheit (280 degrees Celsius). Six times as massive as Earth, Gliese 1214 b is less than three times as wide, falling between the Earth and the solar system's ice giants Uranus and Neptune in size.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The high temperatures of the planet may affect the hydrogen and carbon chemistry, which could produce a haze in the atmosphere. But determining if the weather is clear or perpetually overcast on Gliese 1214 b would be difficult, as differences in the two atmospheres are small.

"At high pressure and high temperature, the behavior of water is quite different from that on the Earth," Narita said. "At the bottom of the water-rich atmosphere of Gliese 1214 b, water should be a super-critical fluid."

Unlike terrestrial planets, the super-Earth doesn't have a solid surface, making the height of the atmosphere difficult to define. Instead, atmospheric scientists introduce a concept called the scale height, a height determined by changes in the increase or decrease of atmospheric pressure by a set amount. On Earth, the scale height is about 6 miles (10 kilometers), while on Gliese 1214 b it is three times deeper, according to Narita.

"We predict that ionic or plasma water can be seen deep inside the planet," Narita said. "However, we may not be able to find hot 'ice' — high pressure-ices — inside of Gliese 1214 b."

Originally discovered in by the MEarth Project, which tracks more than 2,000 low-mass stars in search of planets, Gliese 1214 b was confirmed by the European Space Agency's High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher in Chile.

As a planet travels across the face of its star, or transits, it blocks the star's light slightly, allowing scientists to determine characteristics about it based on how much the light dims.

Though water is often considered a necessary ingredient for life by scientists, Narita doesn't think that the super-Earth will be promising due to its close orbit, which lies within the star's habitable zone, the region where liquid water can exist.

"Although water vapor can exist in the atmosphere, liquid water — namely oceans — would not exist on the surface of this planet," he said. "So unfortunately, we do not think this planet would be habitable."

Narita's team intends to continue studying the planet with spectroscopic observations in the visible wavelength, and anticipates that other astronomers will follow.

Follow SPACE.com @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky