Saturn's Rings Bombarded by Space Rocks

Saturn's rings just can't catch a break.

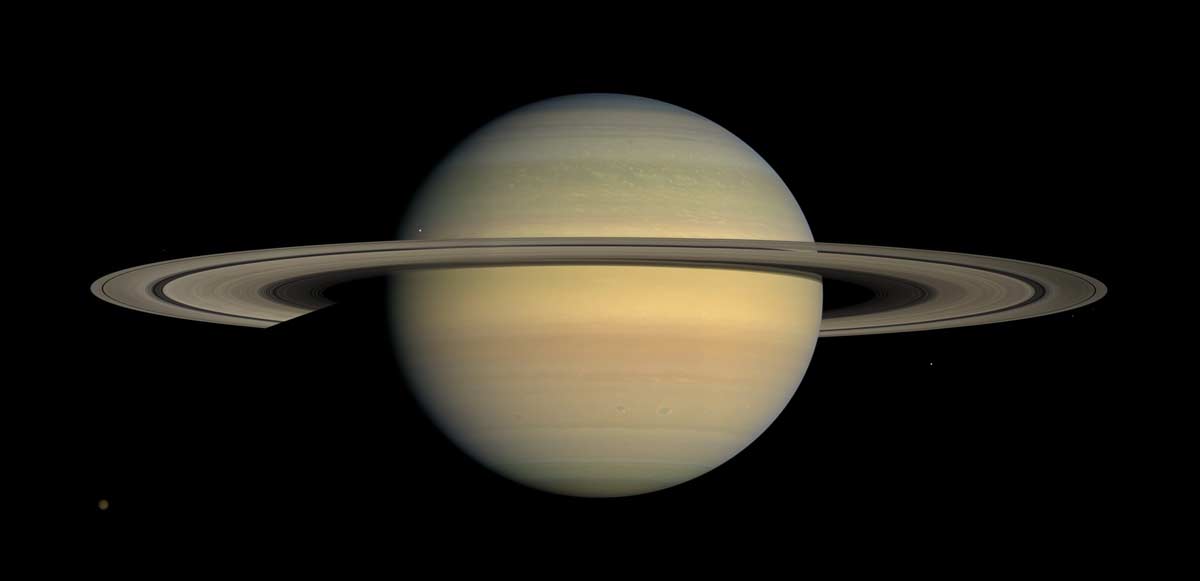

The billions of tiny particles of rock and ice orbiting Saturn are constantly hammered by other space rock fragments. Now, thanks to a rare occurrence, scientists have seen these cosmic impacts in action.

Saturn's orbit around the sun is equivalent to about 30 Earth years. On about the 15th year of that cycle — which happened most recently in 2009 — the lengths of Saturn's day and night were equal, which allowed the sun to cast a shadow on the planet's rings. [See Photos of Saturn's Dazzling Rings]

This presented a unique opportunity for Matthew Tiscareno, a Cornell University planetary scientist.

"During the equinox, the sun is shining edge-on to the rings," Tiscareno, whose new research is detailed in tomorrow's (April 26) issue of the journal Science, told SPACE.com.

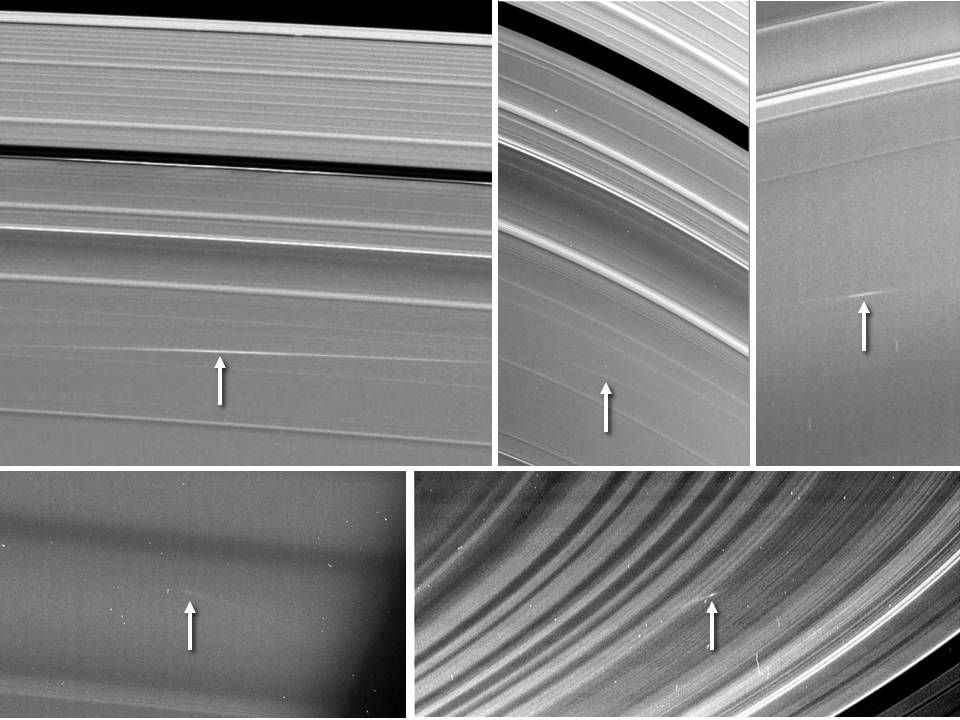

This angle makes it easy to see clouds of dust, called ejecta, pluming up from the rings.

Once Tiscareno and his team observed a dust cloud anytime between one and 50 hours after the initial impact, they had to work backward. By measuring the length and tilt of the cloud, the research team could see what kind of impact created it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In 2009, NASA's Cassini spacecraft in orbit around Saturn monitored three different dust clouds. When Tiscareno and his team analyzed Cassini's findings, they saw that the ejecta clouds were created by "streams of meteoroids" plunging through the ring plane.

At first, Tiscareno thought that single meteoroids impacting the ring plane probably created these clouds, but that kind of impact didn't fit with what they were seeing.

Single meteoroids would most likely move straight through the plane, creating a hole, but not a cloud. The cloud is more indicative of a group of meteoroids, displacing a lot of dust at once.

"We have discovered clouds of ejecta that are being thrown up out of Saturn's rings," Tiscareno said. "Basically, we're catching impactors in the act. We're actually observing not the moment of impact itself, but the ejecta flying in all directions."

After the initial impact, the material displaced by the stream of meteoroids shoots pieces of debris up and away from the ring plane. These pieces of dust are flung out of their normal orbit and pushed into a new, slightly different one, Tiscareno said.

The clouds of ejecta actually have to pass through the ring plane twice during one orbit. The dust particles still orbit in the same direction as the rest of the rings do, but they are slightly off kilter, Tiscareno said.

Eventually, the dust settles, and most of the ejecta are pulled back into orbit within the ring plane.

These findings could help scientists understand the nature of space rocks in the solar system at large, Tiscareno added.

"The most scientifically useful aspect of this discovery is that, for the first time, we are directly measuring the abundance of intermediate-sized things flying around the outer solar system — larger than specks of dust but too small to see individually through telescopes," Tiscareno said. "We are able to do this because Saturn's rings are acting as an enormous detector, with a surface area more than 100 times the surface area of the Earth."

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.