Our Sun Is Moving More Slowly Than Thought

The sun is zipping through interstellar space more slowly than once thought, suggesting the giant shock wave long suspected of existing in front of the sun is not actually there, researchers say.

These new findings may influence what scientists know about high-energy cosmic rays that can endanger astronauts, they added.

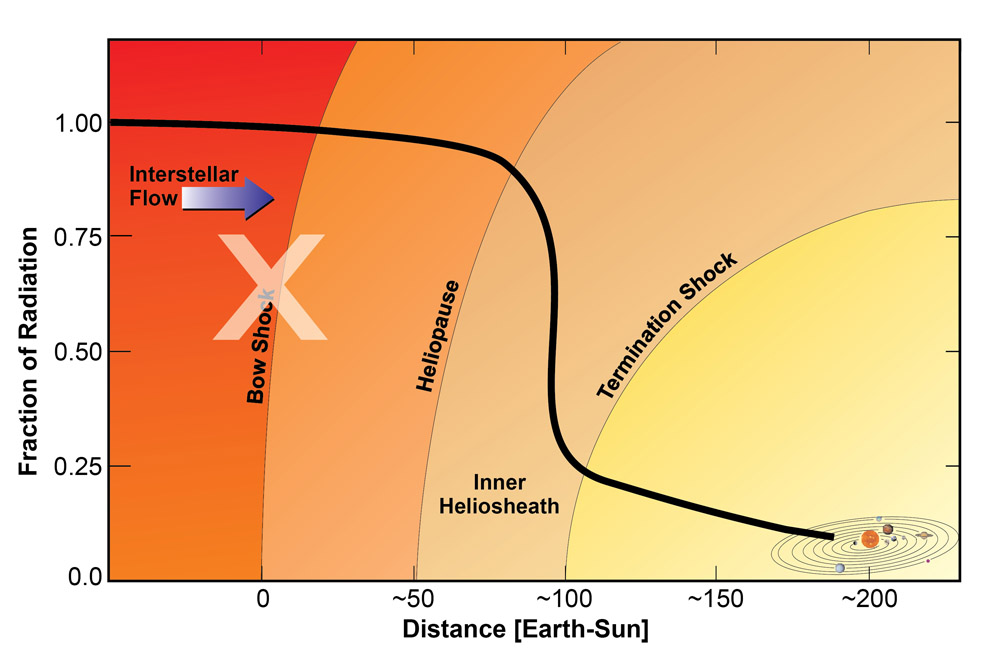

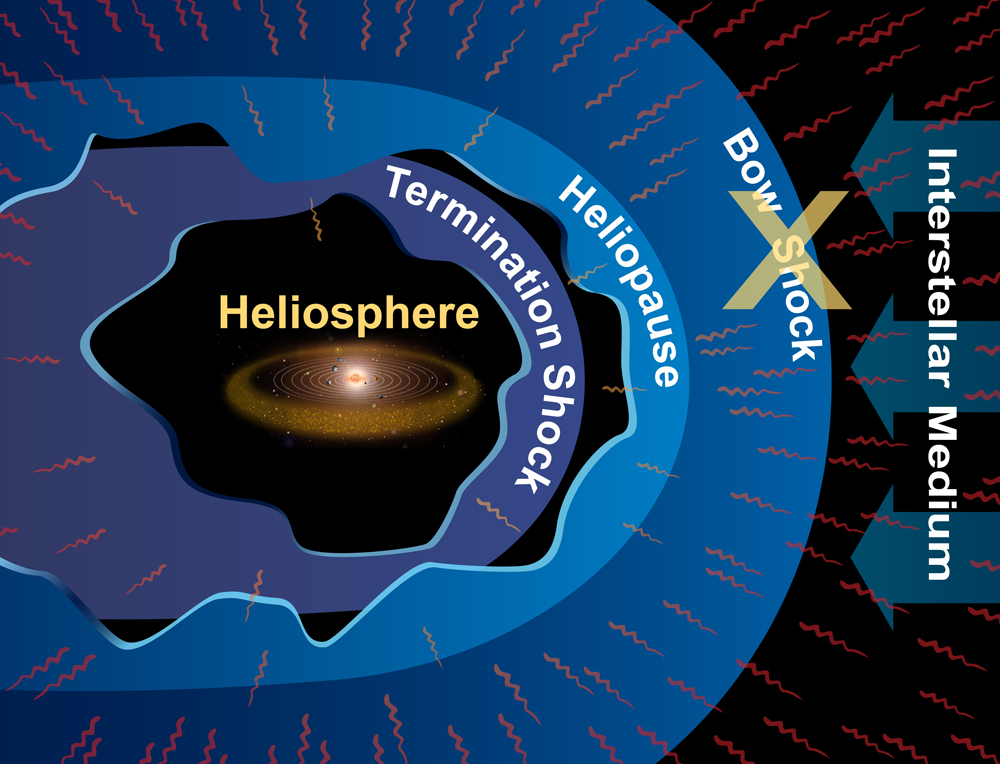

The sun and its planets are cocooned within a bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields known as the heliosphere. The edge of the heliosphere, where it collides with interstellar gas and dust, is called the heliopause, and marks the outer limit of the solar system.

For about a quarter century, researchers had thought the sun was moving fast enough in space for our heliosphere to generate a shock wave known as a bow shock as it plowed through interstellar matter.

"The sonic boom made by a jet breaking the sound barrier is an earthly example of a bow shock," said study lead author Dave McComas, a space scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. "As the jet reaches supersonic speeds, the air ahead of it can't get out of the way fast enough. Once the aircraft hits the speed of sound, the interaction changes instantaneously, resulting in a shock wave."

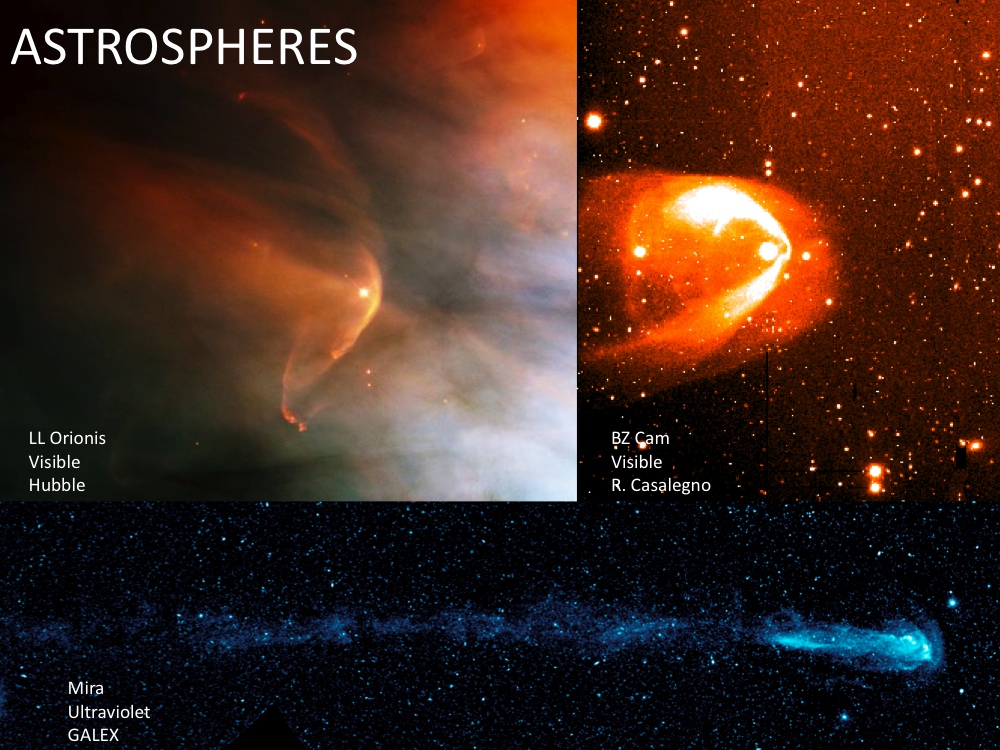

Astronomers have seen these bow shocks of plasma before in space, with counterparts of the sun's heliosphere around distant stars known as astrospheres. [Amazing Sun Photos from Space]

"By studying our heliosphere in detail, we can learn more about the whole picture of how astrospheres work around stars," McComas said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Our slower sun

New observations now show that our sun is traveling slower than before thought. As such, it moves too slowly to generate a bow shock.

"We've now discovered our sun doesn't have a bow shock — it's surprising, and slightly shocking, and much work needs to be redone now," McComas told SPACE.com. "The astronomical community spent the last two or three decades studying something that doesn't exist."

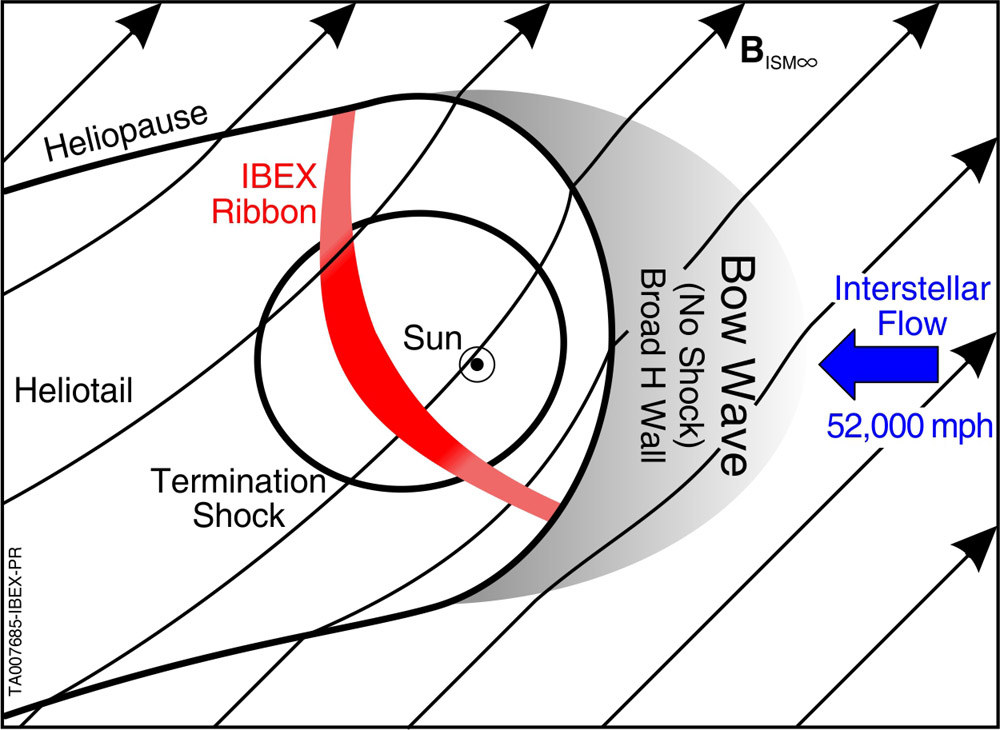

Data from NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), a small spacecraft remotely imaging the nature of particle interactions at the edge of our solar system, reveals our sun is zipping through the local interstellar cloud at about 52,000 miles per hour (83,700 kph). This is roughly 7,000 mph (11,250 kph) slower than previously thought — a dip in speed that by itself would drop the pressure the heliosphere experiences by about one-quarter, enough to keep a bow shock from developing.

"The instruments we have to directly observe our motion with respect to the local interstellar medium are more modern, for more precise measurements," McComas explained.

IBEX data and earlier observations from NASA's two Voyager probes also show that the interstellar medium's magnetic field is stronger than previously believed. This means the sun would have had to move even faster than previously thought in order to generate a bow shock. Altogether, this suggests that a bow shock upstream of the sun is highly unlikely.

"While bow shocks certainly exist ahead of many other stars, we're finding that our sun's interaction doesn't reach the critical threshold to form a shock, so a wave is a more accurate depiction of what's happening ahead of our heliosphere, much like the wave made by the bow of a boat as it glides through the water," said McComas, principal investigator of the IBEX mission.

Heliosphere unmasked

A better understanding of the heliosphere could shed light on how it protects us against dangerous high-energy cosmic rays emerging from deep in outer space.

"The heliosphere screens out about 90 percent of cosmic rays," McComas said. "If not for the heliosphere, cosmic rays could affect things like human space travel and even potentially things on Earth. It's interesting to consider that maybe astrospheres are needed as a prerequisite for life around stars, to protect systems from galactic cosmic radiation."

The fact that our solar system lacks a bow shock could actually mean we are slightly more protected from cosmic rays than before thought.

"The slower speed the sun is traveling at with respect to the local interstellar medium means that at the moment, there is less compression of the heliosphere, so there's a larger region to deflect cosmic rays," McComas said. "However, in the distant past, as the sun goes in its orbit around the galaxy, it surely went through dense clouds, so maybe the heliosphere got squeezed then, and we were more affected by galactic radiation. Surely that will happen again in the distant future."

The scientists detailed their findings online May 10 in the journal Science.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us