GeneSat-1: Small Satellite Tackles Big Biology Questions

LOGAN, Utah--If humans are to embark outward beyond low Earth orbit, research scientists are faced with a set of perplexing challenges. Chief among them is a better grasp of the biological effects that occur from exposure to the space environment--particularly from radiation and reduced gravity.

Data gleaned from ground and in-space studies can help create countermeasures to the injurious impacts from long-duration space stays on the Moon, Mars, and elsewhere.

There are plenty of large problems out there to solve. And that's where small satellite technology in the form of a GeneSat-1 might play a big role.

The concept of the GeneSat-1 was showcased at the 19th Annual Conference on Small Satellites, held here August 8-11 and sponsored by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Utah State University.

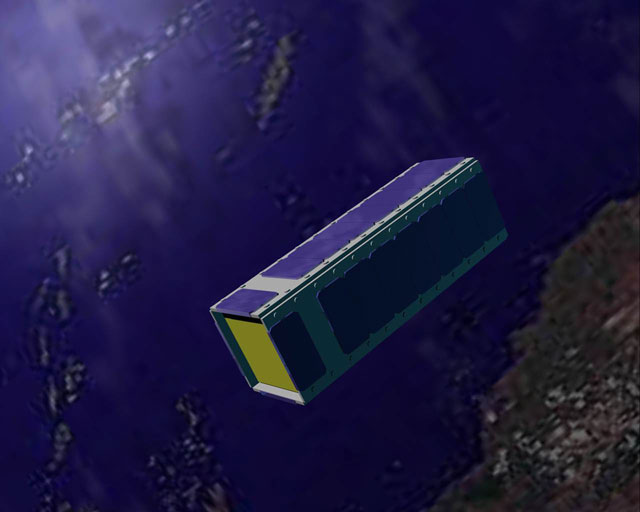

Small, fast, cheap: these watchwords meld together to shape the idea behind GeneSat-1, a 22 pounds (10 kilograms) nanosatellite that's actually the product of three smaller "cubesats" fastened together.

While diminutive in size, GeneSat-1 would be a fully-automated, miniaturized spaceflight system that provides life support, nutrient delivery, and performs assays for genetic changes in E. coli--that's the abbreviated name of the bacterium Escherichia (Genus) coli (Species).

Work in progress

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For the moment, GeneSat-1 is a work in progress and could be wrapped up by year's end.

But the small satellite is "temporarily on hold" pending launch availability and funding, explained John Hines, the project manager at California's NASA Ames Research Center. To date, roughly $6 million has been spent on the work over the last two-and-a-half years, he told SPACE.com.

The evolution of the idea into flight hardware has been under the wing of the "Astrobionics" project at the center.

Astrobionics is NASA lingo for fleshing out technologies to support and facilitate safe and effective human exploration missions, including autonomous medical care, robust life support systems, and dynamic research instruments and hardware.

The overall GeneSat-1 effort is a cooperative endeavor between NASA and various universities partnered at the Space Technology Center, managed by San Jose State University, including Santa Clara University, California Polytechnic State University, and Stanford University.

Express yourself

Behind the GeneSat-1 idea is an integrated analytical fluidics card assembly. This little piece of mini-hardware--about the size of a playing card--is outfitted with a pump, valves, microchannels, filters, membranes and wells--elements that maintain the biological viability of the select microorganism.

A built-in thermal control system keeps biological specimens at just-right temperatures as GeneSat-1 slips through the space environment.

Once in orbit, samples of E. coli are dispensed into assay wells of the fluidics card. Sugar water is released to activate the experiment, with a suite of sensors monitoring the bacteria. Expressions of genetic signals are to be detected by the ultra-small optical system.

Gene expression is a process in which a gene is profiled by revealing information encoded within the gene into protein or RNA.

Chicken and egg

If launched, GeneSat-1 would be the first action item within the In-situ Space Genetic Experiments on Nanosatellites (ISGEN) Technology Demonstration Project.

"The first milestone is to get the flight experience and heritage with this device," said Bruce Yost, deputy project manager of the GeneSat-1 work for Defouw Engineering at NASA Ames.

"In the space world, to be able to fly the next new mission, you have to have flight heritage from the previous mission. But if you don't fly the previous mission...it's kind of a chicken and egg thing," Yost told SPACE.com.

GeneSat-1 is taking a crack at breaking the chicken and egg issue, Yost added, "to validate this technology as a credible candidate for a lunar or deep space mission."

Four-sides of solar cells

Along each of its four sides, GeneSat-1 would be decked with solar cells. Also the tiny satellite totes secondary batteries that the solar cells charge for operation when it is being shadowed by an eclipse.

"When we're in Sun, we run on the solar cells and charge the batteries. In eclipse, just the batteries power the spacecraft," Yost said. If placed into orbit in a roughly 340 miles (550 kilometers) altitude above Earth--calculations show that GeneSat-1 would reenter in about four years, Yost noted.

"We would like to have students and other engineers exercise and operate the spacecraft after the biology has been completed for at least some of that time. Of course, if a critical system were to fail or wear out, like the batteries or communications radio, then that's it ... since we do not have a lot of redundancy in the design," Yost said.

Intersection: smallsats and biological research

As a potential forerunner to follow-on technology modules, GeneSat-1's goal is to help devise protocols for the study of genetic changes arising from the unique space environment. Back here on Earth, advances in therapeutics have come from delving into biological mechanisms and pathways at the molecular level.

Similarly, skill in thwarting bone density loss, muscle atrophy, and a stressed immune system--debilitating effects observed on long-duration space missions--could benefit from GeneSat-1 and future gene/protein array analyzers flown in space.

Validating the GeneSat-1 in Earth orbit could foster its use to study biological changes in microorganisms and other specimens on the Moon and elsewhere in deep space. Data results are transmitted to Earth, requiring no specimen return.

Just as there have been advancements in small satellite technology, a revolution in the biological and medical sciences has been underway over the past 15-20 years, Yost said. "You don't need large amounts of tissue or samples to probe and understand what it is you are trying to determine," he told the small satellite meeting here.

These two developments - small satellites and biological research--have "intersected quite nicely," Yost said.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.