Lasers Mimic Exploding Stars to Explain Cosmic Magnetic Fields

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Powerful lasers that mimic the effects of supernovas are now helping reveal how the magnetic fields of galaxies may have formed in the early universe, scientists reveal.

Nearly all galaxies, including our own Milky Way, have magnetic fields, ones that might affect how fast stars are born. However, where these fields come from has been a mystery.

The standard model for how these fields form is that tiny magnetic fields, which existed before galaxies evolved, served as cosmic "seeds" that were amplified over time by turbulence in the intergalactic medium. Still, it remains uncertain how these seed magnetic fields arose.

One notion is that they were generated by the so-called "Biermann battery effect," which is based on how the hydrogen making up most of the gas in the universe is made of negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons. Since electrons are much less massive than protons, they are much easier to push around, and outside pressures acting on both can drive electrons away from protons, creating an electric field. Eddies within the hydrogen can then set these electric charges spinning, generating magnetic fields. [The Strangest Things in Space]

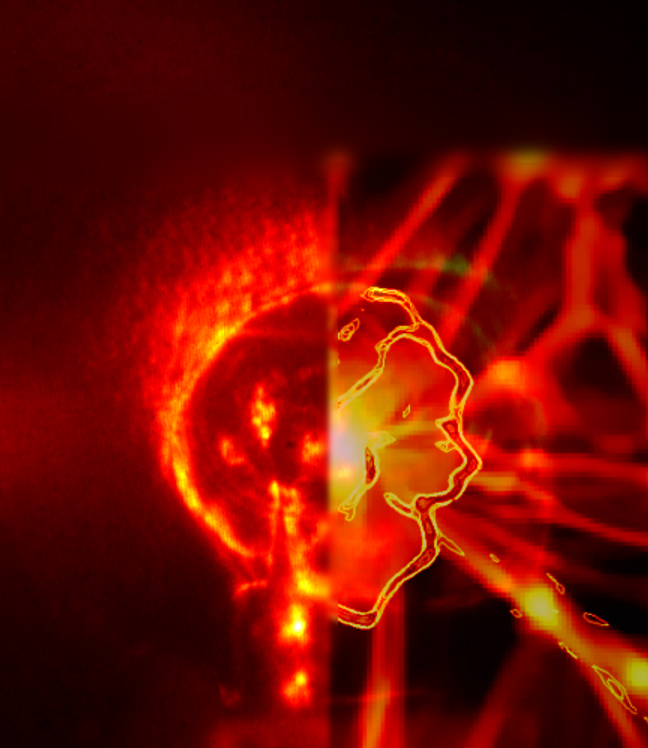

To see if seed magnetic fields could form via this effect, scientists experimented with high-power lasers at the LULI laboratory in Paris to recreate extreme conditions seen in outer space. The green lasers were used to blast a carbon rod just 500 microns thick, about five times thicker than a human hair, delivering more energy on its surface in an instant than Earth would receive from sunlight for that same instant.

"This mimics an explosion or a blast — say, like a supernova," said study lead author Gianluca Gregori, a physicist at the University of Oxford in England.

The way the carbon rod flexes in response to this blast generates a shock wave within the low-pressure helium gas the rod is immersed in. This shock wave produces eddies that could in principle create magnetic fields.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We were able to reproduce, albeit in a scaled manner, plasma conditions found in the early universe directly in a laboratory setting," Gregori said.

The researchers successfully generated magnetic fields using the lasers. If ramped up, they calculate that turbulence within the intergalactic medium could on time scales of about 700 million years amplify seed fields to galactic proportions, supporting current theories of how galactic magnetic fields arise.

In the future, the researchers would like to replicate their work with the largest laser available on Earth, the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. "Ideally even more extreme conditions could be recreated," Gregori said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Jan. 26 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us