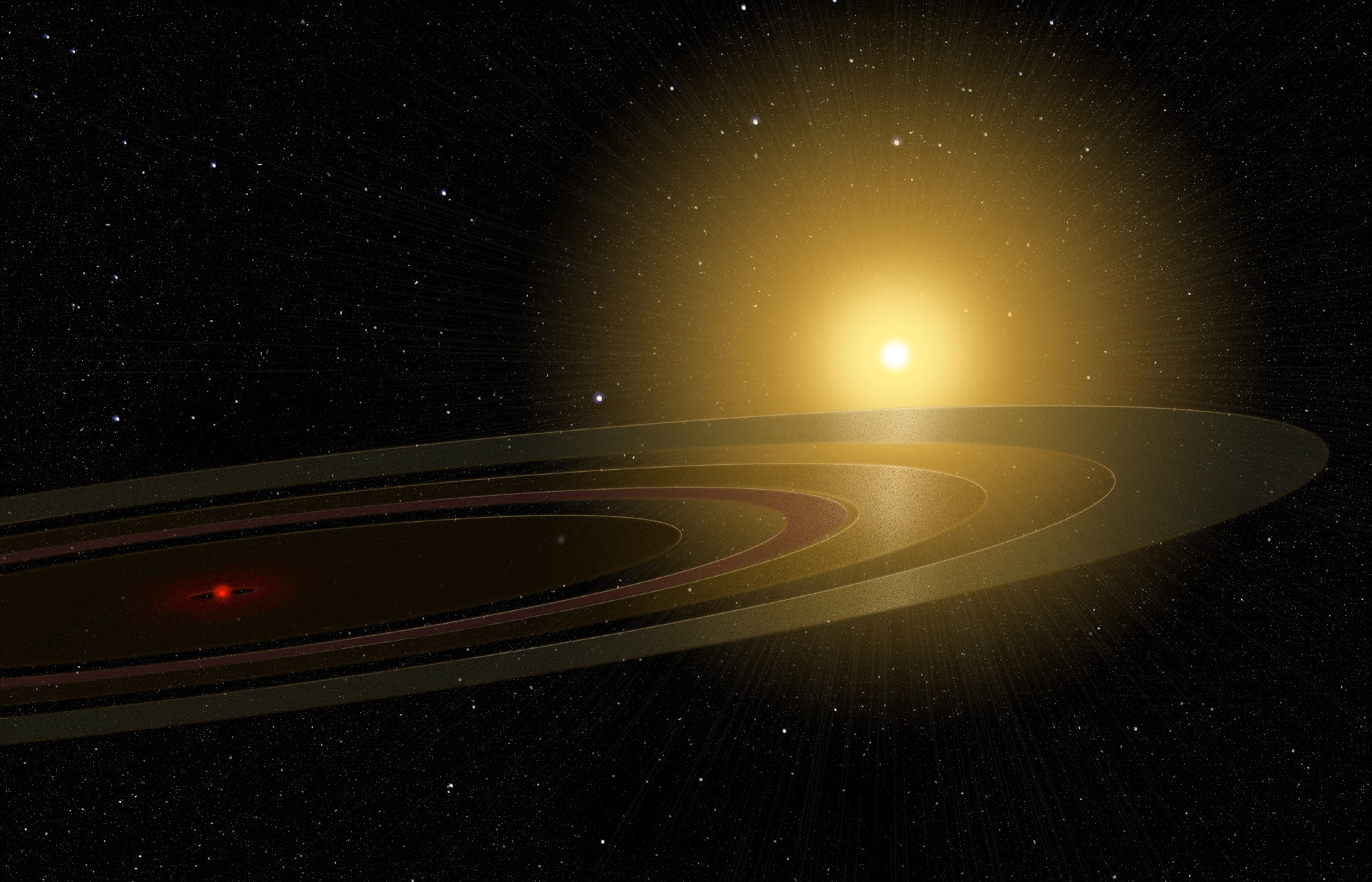

'Saturn on Steroids': 1st Ringed Planet Beyond Solar System Possibly Found

AUSTIN, Texas – An enigmatic object detected five years ago in space may be a ringed alien world comparable to Saturn, the first such world discovered outside our solar system, scientists now say.

The finding, announced here yesterday (Jan. 11) at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, came from studying an unsteady eclipse of light from a star near the mysterious body.

"After we ruled out the eclipse being due to a spherical star or a circumstellar disk passing in front of the star, I realized that the only plausible explanation was some sort of dust ring system orbiting a smaller companion — basically a Saturn on steroids," said study co-author Eric Mamajek of Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile and the University of Rochester.

The find occurred as astrophysicists investigated the Scorpius-Centaurus association, the nearest region of recent massive star formation to the sun, using the international SuperWASP (Wide Angle Search for Planets) and All Sky Automated Survey (ASAS) projects. Specifically, the researchers analyzed how light from sunlike stars in Scorpius-Centaurus varied over time.

One star in particular showed dramatic changes in the intensity of its light during a 54-day period in early 2007, suggesting it was getting eclipsed by an orbiting body.

"I knew we had found a very weird and unique object," Mamajek said. [Photos: Saturn's Rings & Moons]

Weird star clues

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The star in question is technically known as 1SWASP J140747.93-394542.6. It has a mass similar to the sun but, at about 16 million years of age, is much younger, just 1/300th as old as the sun. It lies about 420 light-years away.

Whatever is eclipsing it is relatively close to the star, 1.7 times or so the distance from the Earth to the sun. The Earth-sun distance is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

If a simple spherical object had passed in front of the star, the intensity of the star's light would have steadily dimmed and reached a low point before gradually increasing. Instead scientists saw a long, complex eclipse with significant on-and-off dimming. At the deepest parts of the eclipse, at least 95 percent of light from the star was getting blocked by dust.

The nature of these shifts in light – the "light curve" – was very similar to that of EE Cephei, a hot, giant star occasionally eclipsed by a companion star that is surrounded by a thick protoplanetary disk. However, instead of just one dip in light as one would expect of a single disk, Mamajek and University of Rochester graduate student Mark Pecaut saw several dips.

The eclipsing body seems to be an object "with an orbiting disk that has multiple thin rings of dust debris," Mamajek said.

This would be the first system of discrete, thin dust rings detected around a very low-mass object outside our solar system, he noted.

So far Mamajek and his colleagues have discovered one dense inner disk and three tenuous outer disks, respectively named Rochester, Sutherland, Campanas and Tololo, after the sites where the eclipsed star was first detected and analyzed.

"Each of these rings is probably made of thousands and thousands of rings," Mamajek told SPACE.com.

Alien rings around another world

The outermost ring stretches up to 37 million miles (60 million km) away from the body it encircles. If the rings are similar to Saturn's, their combined mass is probably as much as eight times that of Earth's moon.

"Amateur astronomers can really look at this star with a backyard telescope and help us learn more about this system through monitoring it for more eclipses from the ring system," Mamajek said.

Many questions remain about the nature of the ringed body: for instance, whether or not it is a planet, a very low-mass star, or a kind of failed star known as a brown dwarf. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

If it is less than 13 times the mass of Jupiter, it would likely be a planet similar to Saturn. If it is between 13 and 75 times Jupiter's mass, it would be a brown dwarf. If larger still, it would have enough mass to sustain nuclear fusion, making it a star.

Future telescope observations can determine how much of a gravitational tug this object exerts on its star, and thus reveal its mass.

Mind the gaps

Just as interesting as the rings themselves are the gaps between the rings; gaps usually are signs that massive bodies are sculpting the ring edges. If this mysterious object is a planet, moons could be carving these rings; if it is a star, it could be newborn planets that are responsible.

"One might imagine rings around the smallest stars like rings one sees around Saturn," Mamajek said. "Our inner solar system could've looked like this long ago in its first tens of millions of years."

Future all-sky monitoring projects such as the proposed Large Synoptic Survey Telescope being built in Chile could discover even more ringed systems eclipsing stars.

"I think these rings are how we're going to study moon-forming disks around gas giants," Mamajek said.

The findings, detailed by Mamajek, Pecaut and their colleagues yesterday, are scheduled for publication in an upcoming issue of the Astronomical Journal.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us